Contemporary Paintings > Fine Art Today had the luxury of sitting down with amazing painter Nick Patten, who offered some engaging thoughts about his process, inspiration, and more. So impactful were they that we’ve decided to quote him in full.

Exhibition Of Nick Patten Paintings:

February 5-28, 2021 | George Billis Gallery

How Process Feeds Inspiration: Paintings by Nick Patten

Fine Art Today: Let us begin with your creative process. What inspires you, and once it hits, how do you approach a painting?

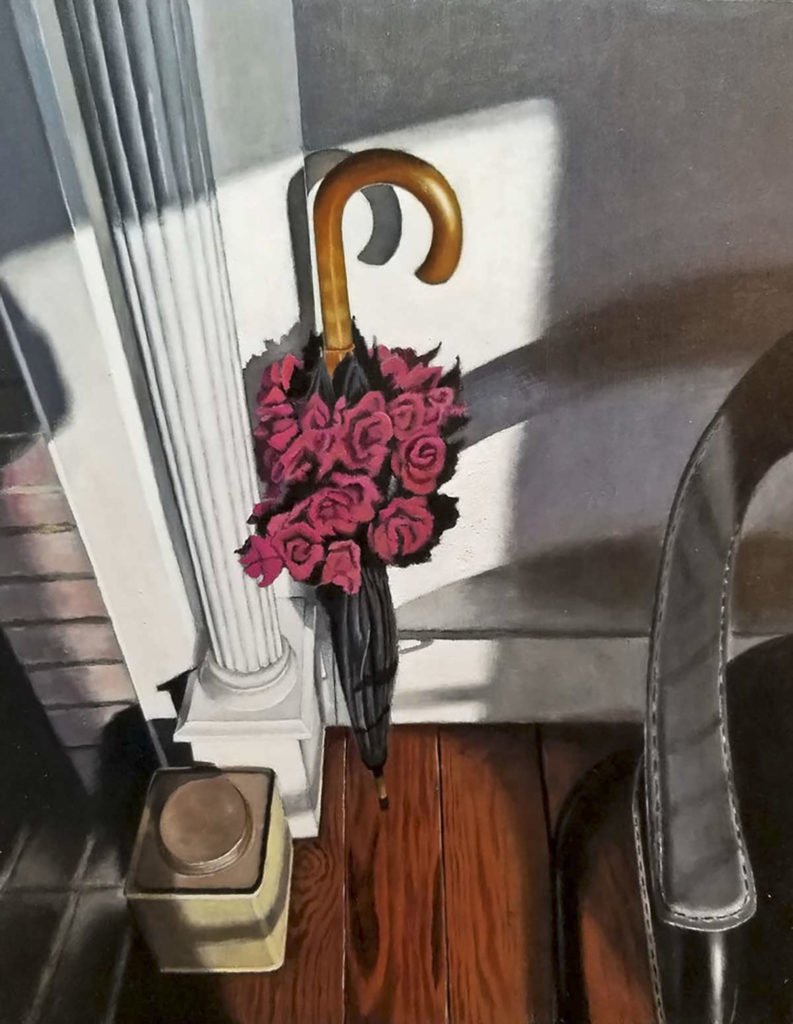

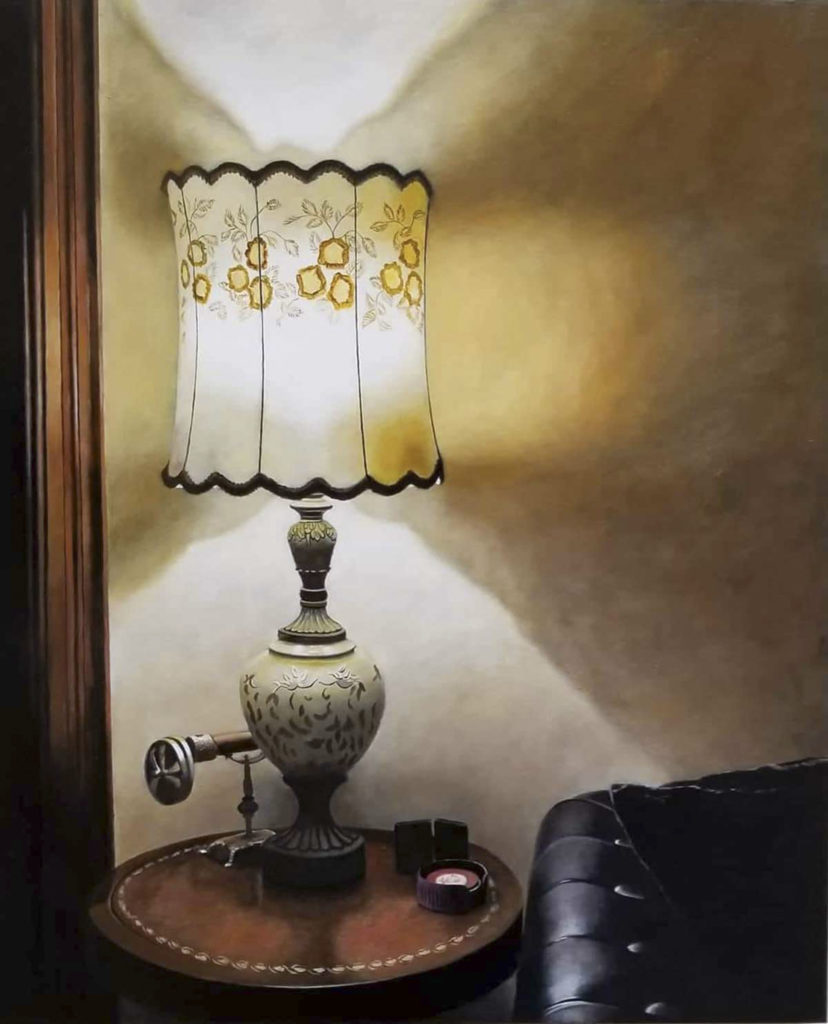

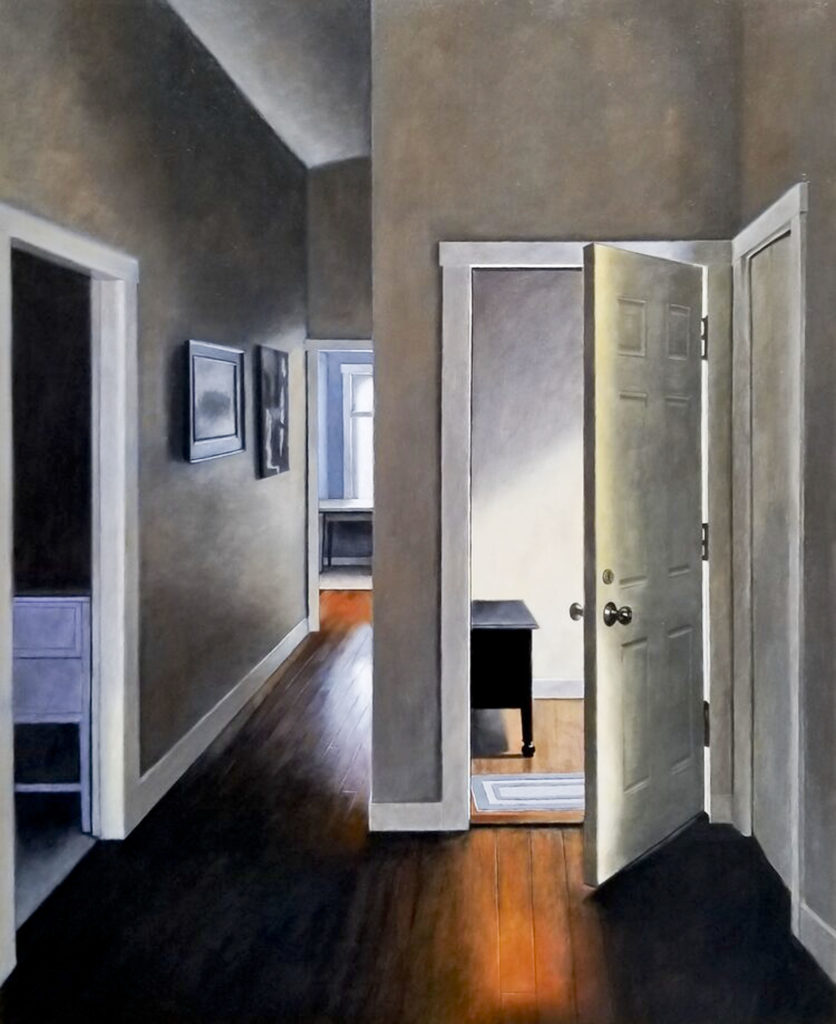

Nick Patten: I guess it would be fair to say that my process feeds my inspiration. By that I mean part of my process seems to be a natural (or a second nature by now) way of seeing things. I see subjects for paintings when I’m not looking for them all the time. It hits me in the gut, to use a loose reference. I see something and it gives me a feeling somewhere between pleasure and edgy. Sometimes it leans toward melancholy, in that there is a sense of isolation in many of my interiors.

Sometimes a scene gives me a sense of a moment — something just happened or is about to, and I’m privileged enough to witness the moment in between. In my statement that I wrote over 20 years ago, I say that I paint what I want to see. That is the essence of what I’m trying to do. I see a scene, and sometimes I know immediately that I must make it into a painting. I’m compelled to do it.

I always start a painting the same way, regardless of the subject matter. I start by laying down a gray ground in oil paint. I haven’t wavered from this too many times over the years, but when I have, it would have been to experiment with a yellow ground or a sepia ground. From there I draw in a grid in white colored pencil that matches the grid I have put over the source photo. I gravitated toward the grid because it facilitates my getting to the meat of the painting faster and more accurately.

I don’t love each step in a painting equally. I love the last 10 percent most, and want to get there as fast as I can. Once I realized that about myself, I knew I wanted a process that would insure I wouldn’t need to waste time on correcting simple issues like proportion or perspective. So, with the grid in place, I draw in the scene, again using a white colored pencil (as that will never bleed through the paint in time like graphite can). Once I have a linear drawing in place, I start my black and white underpainting. It is not as realistic as my final version, but it is far from a sketch because it’s at this point I can make real decisions about what I have. If it works in black and white, it will usually work in color.

For me, composition is as important as any other element of a piece, and I can assess it best without the distraction of color. Fortunately, it is also early in the process, so if there are mistakes or flaws or any changes I want to make, they are easier to make at this stage.

Next comes color, and I work in layers. The first layer of color is my least favorite part of the process because I’m basically destroying an otherwise competent black and white painting and I’m left with an awful-looking mess, as the first layer of color rarely looks good. But after the second layer of color, I start to hit my stride and I am beginning to see the promise the painting holds. It starts to look good, and I can get a better sense of what my choices will look like in the end.

Third layer of color confirms these choices, as I start to tweak my colors and values here. This could be a stronger blue, and that can be a softer ochre — those choices add to what I hope will be the overall impact of the final painting. From here, I have what many would consider finished. This is the beginning of the last 10 percent that is most of the reason I paint!

Here I assess each section of the painting, deciding in some cases the surface and the color is exactly where I want it to be. Other areas may need the same color again, but with a new layer it will solidify better, make a stronger impact. There is still room for changes of heart here as I might change a color or add a detail, but basically I’m reinforcing areas of the painting by laying down another layer or two. But like I say often, it is only certain areas that require it.

In a recent piece, I had all the painting exactly where I wanted it in three layers of paint except for a couple of areas. One area was a sculpture pedestal that required two more layers of paint to get a very unusual yellow green that I wanted to portray. The other areas were parts of the painting that were pure white. Even though I use a paint called Radiant White by Gamblin, to get a real full-blown white, I usually paint it five or six times — one layer of pure white straight from the tube after another.

By the way, I always paint from photos, and I rarely use a paint medium to thin my paints. I never mix medium in with the paint; I will only dip the corner of my brush in medium from time to time, just to loosen it up. This gives me more control, and a solid confidence of the structure of the painting, as without mediums interacting differently with different colors, I know I’m always painting in an archival way and my surfaces dry in the order I lay them down, thus avoiding the risk of cracking in a year or two.

There are a few different ways that I know when a painting is finished. Some are ideal, and some are real-world issues. Real-world issues tell me a painting is finished when I have bumped up against a real-world deadline. Maybe a show is opening, or a promise has been made, but the real world enters the studio more often than one might think. Most painters I know who do it for a living are always under some form of time constraint or another. I’m certainly not unique. In many cases, it serves to bring out the best in us because with less time come fewer excuses. And sometimes, that brings with it a laser-like focus that was needed all along.

But to be totally honest, I am not sure I ever know when a painting is finished. I do have a road map for each painting that I make. I know how to begin, and my beginning is a panel primed with a gray oil paint ground, then a grid, then the drawing on the grid, etc. I know how to make paintings — better put, I know how to make my paintings! I know where I am at all times during the process, and what still needs to be done. Simple!

It starts to get tricky and subjective when I am on my last layer of paint. It is here that, though I should be on my last layer, I don’t always know that for sure. This is really the most exciting stage of any painting, because here is where the art leaves the craft. Here is where I’m making decisions based on my instinct and aesthetic. The draftsmanship, the palette, the composition have all been decided and basically executed. That is the craft.

The art involves the subtle nuances that I start to see when the painting is in its final stages. A little darker here brings out a drama, but sacrifices a softness. I want this area to be cool colors to balance something else, but I find the cool color fights the balance, so I warm up the cool color. Sounds like I could be in a kitchen, with a pinch of this and a dash of that, and that might be a good analogy. This is the time in the painting that I can’t predict, I just don’t know, and the reason I don’t know if I need a day or a week or a month is that I must try things out to see what they will look like before making a final decision.

My eyes service my feelings. When I get a painting to a stage where it pleases my inner self, where it calms the intensity I felt when I started going after what I wanted to see, then the painting is complete. But is it really? No, not really, because I might see something else in a week, some other thought might pop into my head that will influence my decisions, and maybe influence what I now want to see. When this happens after the paintings have left my studio, I always make a mental note so that I remember to consider revisiting that image again.

Fine Art Today: Briefly illustrate this process for us. Could you dive into the process of a specific work? Perhaps you can recall when, where, and how you were moved to create it.

Nick Patten: “Essence Redux.” This painting came about from work I did from a series of photos I took of a brownstone in downtown Troy, New York, which is my hometown. I saw online that there was to be an open house for this property, and I contacted the Realtor, explaining who I was and what I did, and asked for permission to come during the open house to take photos of the house to make paintings from. They contacted the owner, who agreed to let me attend. I knew from the address what the house would look like, and it exceeded my expectations. They had a beautiful area they used as a dining room and this is a scene from that area.

I had painted a few other views of this area, and still I had more to paint. The light in the room was all natural, and from the exquisite fern to the tasteful dining room set, I felt an elegance in this room. So my process was as I described above: applying a grid to the photo, and then resizing that grid and applying it to the panel where I had already laid down my gray ground. I followed my usual steps of drawing the image, and then the black and white underpainting, all through to the various layers of color. During the whole process I was undecided about how to treat the area of the wall the picture occupies in the final painting.

At the very end, I thought of what I wanted to add. What we see here is not a painted area representing a painting. What I did was to take a .jpeg of one of my own past paintings and print it out in the right size onto a small piece of rice paper. The rice paper receives ink well, and is so thin that the edges are not apparent once I mount it to the painting. Then I painted in a frame around the image. Next I “pushed the image back” with a thin layer of transparent white oil paint. Finally, I laid in a few glass effects to further recede the image, using the transparent white paint on top of it all. This is a technique I taught myself, and frankly I have not seen it used elsewhere, but it probably has been. I have employed it in several paintings when the effect was worth it to me. I quite enjoy doing it as it lends a whole other issue to contend with.

To me it makes the painting different. I wouldn’t even know what to call it — though some have referenced these as mixed media paintings, that might be too much for my definition. It does in this case wind up not being a painting within a painting, but more accurate would be a photo of a painting within a painting!

Fine Art Today: What about narrative? Do you ever seek to create narratives in your works, revealed through, say, your use of light, surface, etc.?

Nick Patten: I have always maintained that I try not to have a narrative in my paintings. I know that is probably not achievable 100 percent of the time, but I can say I never start a painting with a narrative in mind. For me it is more about the scene and how it has impacted me. I know once one mentions emotions, then the idea of narrative comes into play, but I don’t anticipate what viewers’ emotions will be.

I had a commercial gallery open to the public for 12 years on Cape Cod. I painted in one room and showed my work in the other two. I experienced the range of reactions firsthand over many years. One person would view a painting of a single chair at the end of a hallway and see loneliness and melancholy, and someone would come in not a half hour later and remark that the painting was comforting and warm to them because the chair in the painting was just like a chair their grandmother owned. I can’t anticipate what experience in life one might have when they come to one of my paintings, and therefore I don’t try to.

Fine Art Today: When it comes down to it, what are your primary goals in painting? What do you hope viewers take away?

Nick Patten: Through working from photographs with the aim of creating believable paintings, I strive to bring a quiet drama to everyday scenes. My paintings are never intended to be “photographic.” In part, my aim is to make paintings where the content of the image is most compelling, and how the painting was made is secondary. In a sense, attempting to make the work exceed the medium, my goal is to be able to paint what I want to see.

I hope that a viewer of my work takes away a memory of the work to such a degree that it remains in their consciousness. I’ve been told this happens by many people over the years, which is the only reason I feel entitled to even mention it as it may sound arrogant. Of course, in a practical sense, I hope the compulsion is so strong that they take away the painting itself, leaving behind money, which allows me to continue to support my life — which is spent painting.

Selling is important only to the point it provides one the ability to have a life as a painter. We all must eat, and clothe and shelter ourselves. We all have work that supports that. I don’t shy away from this concept in the least. What I don’t do is to make paintings in anticipation of a sale. If I knew what would sell, I might consider painting it. But since I don’t know, I rarely think about it. It really is that simple.

Fine Art Today: Talk to us about the artists who’ve inspired you, whether historical or contemporary.

Nick Patten: A select list (there are many more) would include Balthus, Wyeth, Rothko, Morandi, Gerhard Richter, Edward Hopper — but not to the extent most people believe. Same with Vermeer, some, but not to the extent people might think, even though one critic referred to me as “an American Vermeer,” and that label kept getting repeated in subsequent articles and reviews. It is flattering and embarrassing in equal measure. The influence of Vermeer and Hammershoi on me are after the fact. I was already on my own path before I even discovered Hammershoi, and only recently have I related to Vermeer at all.

The most influential event in my life pertaining to my painting was seeing a Balthus retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum in 1984. I had never seen paintings with such an impact. Large scale, and the pieces he did in tempera over years had the look of stone. The surface of the paintings looked like fresco, and the images were as compelling as anything I had ever seen. It first gave me the idea of how much more a painting could be. The idea of a painting being an independent object almost with a life of its own came to me from seeing that show.

It was almost unbelievable to me when I discovered Morandi. I had been painting bottles on tables for several years from drawings I made from my imagination. Then to discover Morandi was both inspiring and devastating. Devastating because it appeared to me whatever I would do had been done to perfection, and it intimidated me. But I was much younger and had not found my own voice, so it was understandable from my vantage point today.

Another critical exhibition to me was the retrospective at MOMA of Gerhard Richter. I was in love with his realist paintings then as I am now, but also a fan of his squeegee paintings. Again, I got the sense of a painting as an object, like I did with Balthus. It seemed to me that Richter was surpassing the medium with his images — something I have strived for over the years.

Finally, there are too many contemporary artists to mention that have influenced me, and I would not want to list them for fear of leaving someone out. We are in a golden age of realism in my opinion, and there are so many brilliant painters around today it is both humbling and an inspiration to be occupying the same time frame.

Fine Art Today: What has your journey to becoming a successful artist been like? Were you always interested in art, even as a child?

Nick Patten: I have been interested in art for as long as I can remember. I drew as a kid, like so many kids do. I was encouraged and even rewarded at a very young age when I won a school-wide competition with a drawing I made from a book jacket. I think that was the assignment, to copy a book jacket. In any case, I have read that often people will lean toward anything that happens in childhood that they are rewarded for in some way. In my case from about age 10, I was rewarded with attention for my artwork, and I think that could have started a foundation that supported later interest and enthusiasm.

Fine Art Today: Finally, where are you and your artwork in, say, five years’ time? How do you see your work evolving? Are there particular things you seek to achieve?

Nick Patten: I don’t think in five-year terms anymore — or one-year or 10-year. I started painting full-time as an occupation when I was 38 years old. By most careers that is older, but by an artist’s career it could be considered younger. By what I read of the number of painters who never can support themselves from their art through no fault of their ability, I hit the lottery. So, after 28-plus years working at it full-time, at the tender age of 67, my ambitions have changed.

Now I mostly care only about the quality of the work I produce. I have learned through experience that it matters very little to me what someone else says about my work. In other words, I have been fortunate enough to experience very high praise from notable individuals, and when the praise is lavished on a painting I don’t feel especially enamored with, the praise rings hollow to me.

I have won gold medals in shows, and many other prize levels. Only when I feel strongly about the painting that won the prize do I enjoy the prize. I have had an important room in a regional museum devoted to a show of my work, and I was quite pleased by that, but it pales by comparison to the excitement I feel when I finish a painting alone in my studio and I feel it is a good painting.

So I hope my work will continue to grow, and that I will continue to push myself to achieve that aim. As to my career, I don’t expect to be on the cover of Time magazine, and frankly at this point don’t really care about that sort of thing anymore, even if there was a time in my life that I did. Now what I want is to make good paintings, continue to show them in good galleries of note, and have a good working relationship with those gallerists who, after all, are my partners.

To learn more about Nick Patten and his works you can visit his website here.

This article was originally written by Andrew Webster in 2017 and featured in Fine Art Today, a weekly e-newsletter from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine. To start receiving Fine Art Today for free, click here.

Nick is a true modern day master of light & shadow, and his ability to capture it and the many details within a space in a such a way to evoke the emotions of the viewer is truly remarkable ! Love his work !