“What avails a storm cloud accurate in form and color if the storm is not therin?” ~ Albert Pinkham Ryder

Painting as an Intimate Act

BY BRAD ALDRIDGE

(www.bradaldridge.com)

Much of writing about art strikes me as something akin to a technical manual on how one should kiss their lover—a cold analytical treatise on something very dear and personal, as if the way one purses one’s lips sums up the entire experience. Another style of writing about art attempts to psychoanalyze or examine the metaphysics of the experience of creating a painting.

When an artist paints, how they “purse their lips;” that is, what subject matter, materials or techniques they use, is important, but not nearly as important as the intimate union of artist and viewer that should take place. All communication, including painting, is an act of intimacy.

When viewing the paintings that move me the most, I can almost sense the faint warm breath of the artist on the back of my neck, looking over my shoulder and observing their creation springing to life before us. That experience doesn’t come from merely painting to fulfill some deadline, nor does it happen when the artist focuses solely on the practice or virtuosity of their medium. It comes from having something to say, and then having an earnest desire to share that personal “something” with others.

To be sure, if the poet never settles down to the excruciatingly slow and difficult task of learning grammar, then he is very limited in the precision, range and nuance of what he can express. But learning the rules and techniques of writing should always be done with the aim of the writer being liberated to express himself without restraint. Then something wonderful can happen. We come to a meeting of the minds. We get a glimpse into that person, and he or she has the joy of being understood and finding others who see the world as they do. They learn they are not alone. We understand the point they’re trying to convey.

In the illustrious words of Steve Martin in the movie Planes, Trains and Automobiles: “When you’re telling these little stories, here’s a good idea. Have a point! It makes it so much more interesting for the listener!” Often I see paintings (sometimes on my own easel) that seem to be dedicated solely to the practice of their visual grammar and yet they never seem to get to a point. Other paintings never really seem to commit to the hard work of learning their ABCs in the first place.

Unfortunately, we too often settle for merely going through the exercise of painting the lifeless shell of things, or creating widgets to fulfill a deadline. Of course, how else are we to ever become masters of our craft, if not by practice? We must practice, but it must be practice with the ultimate aim of a heartfelt sharing and giving of ourselves.

I had a professor who once told me that a painting needs a reason to exist, that it shouldn’t look like a picture torn out of a magazine, or a meaningless snapshot of the back yard. When I evaluate my own work, I often ask myself, “Am I just adding to the heap?” In other words, is my work joining the mountain of lifeless paintings created throughout history and filling countless galleries today, or is it something inward, personal and beautiful?

One phrase that troubles me a little is when I hear artists say of their painting, “Yeah, it’s kinda fun, isn’t it?” It feels as if some cad is flirting with my sister! To me, that sentiment connotes the half-hearted dabbling of a dilettante. Now, I realize that phrase is often spoken as a self-effacing and humble way to deflect praise of an artist’s efforts.

I also don’t wish to minimize the wonderful importance of fun as a theme or motif in art. Peter Pan is a story, on one level, about fun, but J. M. Barrie took his fun very seriously, laboriously developing an intricate landscape full of characters, and lovingly weaving a complex set of narratives throughout. His painstaking creation is intimate, passionate, and earnest fun.

Another important way I try to keep my art vital and living is to constantly push myself. I love art that works out to the edge of the artist’s abilities. I sense who the artist is not only by what they can do, but what they attempt to do and fail. I don’t have much interest in art that “plays it safe.”

In my best paintings I’m pushing myself hard enough that I’m showing you my strengths as well as my weaknesses, thus sharing with you exactly who I am. We artists put ourselves in an incredibly vulnerable position, but that’s what we signed up for.

In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Ernest Hemingway wrote: [The writer] “does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.

“For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment. He should always try for something that has never been done or that others have tried and failed. Then sometimes, with great luck, he will succeed.

“How simple the writing of literature would be if it were only necessary to write in another way what has been well written. It is because we have had such great writers in the past that a writer is driven far out past where he can go, out to where no one can help him.”

You may be saying at this point, “Alright Brad, so what are some valid and vital themes one might share through art, if simply sharing a beautiful scene isn’t sufficient?” Well, each artist must answer that question for him or herself, but I think a place to start is by looking at the big themes of humanity: hope and disappointment, peace and conflict, love and loss, joy and despair.

Sharing the beauty of a sunrise can be a great theme for painting. Surely the lifeblood of the resurging realist movement in art is that beauty is, always has been, and always will be relevant. But an artist might delve even deeper into the exploration of why that sunrise is so moving, inspiring, and universally hopeful to humankind. Is it merely the correct shade of the red sky, or are there more profound truths at work?

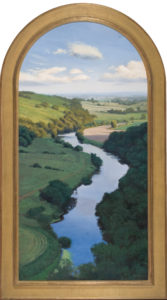

The world in which I find myself has elements of dark and brooding uncertainty and despair, contrasted with longing, beauty and triumph. I strive to endow my paintings with these elements. I often fall short of creating a personal and giving experience, but my best paintings are filled with an intimate sharing of love, honesty, and an earnest hope for the future.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue

Thanks for that. Maybe one of the best articles I’ve read about painting, in part because I just bought a book (Cateura: Oil painting secrets from a master -Leffel) and froze up so tight I could barely lift a brush. I find myself painting to learn always, which is good, but painting for learning plus joy and to move is better. Your piece was entertaining and true and I think I’ll paint today. PS. Writing is often easier.