How two scientists and art lovers came face to face with the Ice Age when they undertook a tour of the Hudson River School Art Trail to follow in the footsteps of Thomas Cole.

Redefining the “Sublime” in the Footsteps of Thomas Cole

By Robert Titus and Johanna Titus

We are scientists: Robert is a geologist and Johanna a biologist. Ours are the two leading sciences of the landscape. We are also residents of New York State’s Catskill Mountains, so it should not surprise anyone that we harbor a passion for the Hudson River School of painters. Fortunately, scientists like us are well-positioned to offer insights on some of the leading themes of that talented group.

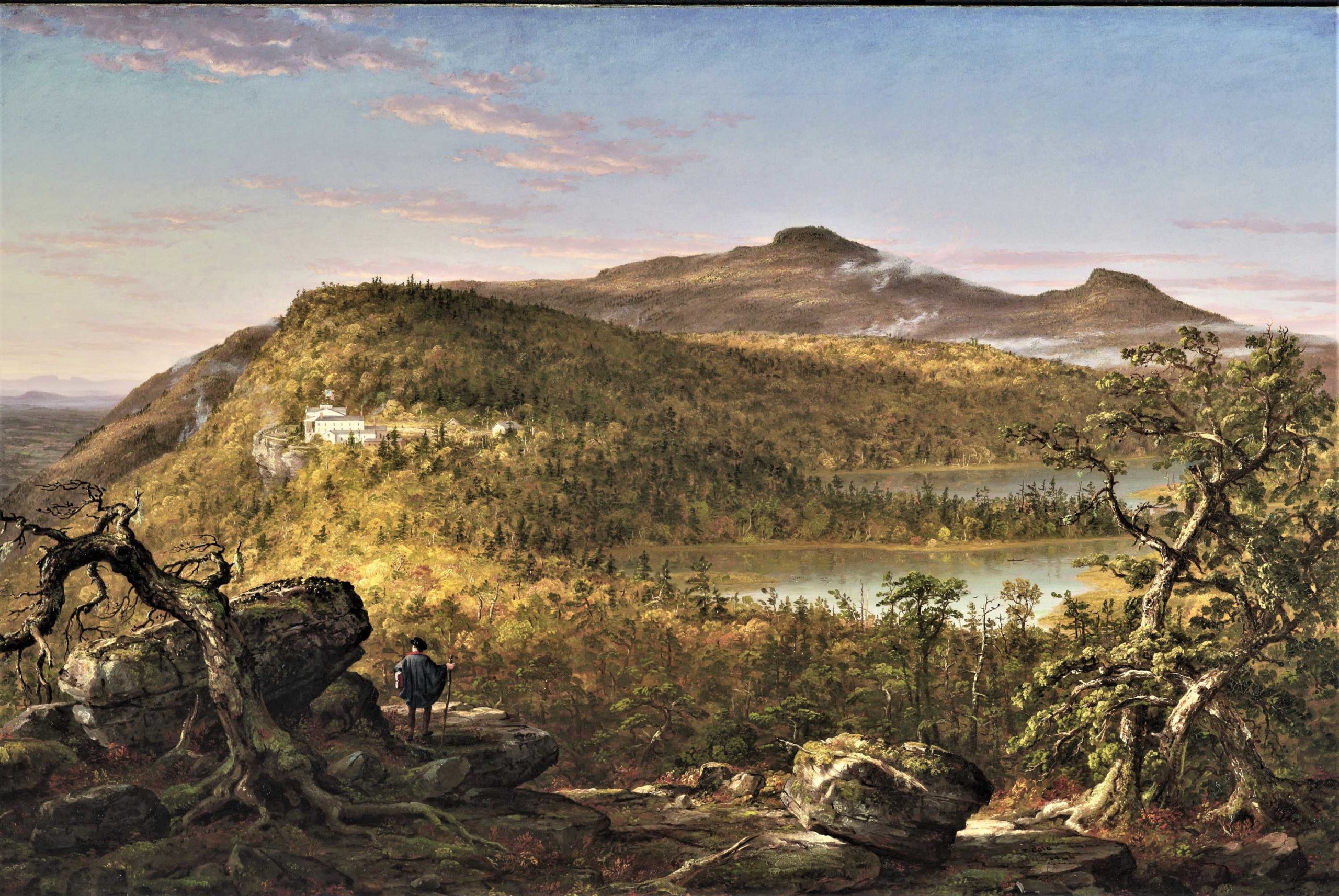

The Hudson River School was America’s first formally recognized art movement. It thrived in the mid-19th century, starting when the English émigré Thomas Cole (1801–1848) began painting landscapes around the Catskill Mountain House Hotel (Fig. 1) at the summit of the “Wall of Manitou,” a towering escarpment along the Catskills’ eastern edge.

Cole first visited this region in 1825, early in his career, when it was still largely wilderness. The landscapes he painted that year contrasted dramatically with the park-like views that had long been featured in European landscape art. Little true wilderness still existed in Europe, but the Catskills offered it in abundance. The atmosphere and effect his canvases evoked soon came to be called “the Sublime.”

Understanding the Sublime is central to understanding the Hudson River School, yet as a word, it has always been difficult to define precisely. To be Sublime, Nature is imagined not just as wilderness, but as wilderness with something vaguely dangerous, even ungodly, about it. Look at any forest scene (Fig. 2) painted by the Hudson River School’s Asher B. Durand (1796–1886). It is easy to imagine entering his dense, wild woodlands, but then you must ask yourself, “Can I be certain I will ever get out of them again?” The answer is no, you cannot, and that, we think, constitutes the scary part of the Sublime.

The two of us have spent much time exploring the Catskills, in and around where Cole worked, and we think there is more to the Sublime than “wild and scary.” Please visit the area and see for yourself: many of Cole’s early landscapes can be seen in what is now the North Lake Campground, which is open to the public. Located in the village of Catskill is Cole’s studio house, Cedar Grove. It was designated a National Historic Site in 1999 in order to enhance understanding of the Hudson River School through architectural preservation, exhibitions, and scholarly study. Having been members of this nonprofit organization right from the start, we have watched with pleasure as it has earned a sterling reputation in all of these pursuits.

Cedar Grove has always reached out to the general public. One example is its publication online of the Hudson River School Art Trail guide. This major endeavor points visitors to many of the exact spots where Cole and his colleagues made their sketches. When we first undertook this tour following in their footsteps, we discovered another, more scientific understanding of the Sublime; we came face to face with the Ice Age. This article presents our icy version of the Sublime.

On the Hudson River School Art Trail

We began at Site 7 on the Art Trail, a location called Sunset Rock (Fig. 3). It’s a rocky promontory that affords hikers a view we consider one of the finest east of the Rockies. Cole painted it several times.

Spread out across the Brooklyn Museum’s version (Fig. 4) are the Catskills that first captivated Cole in 1825. In the distance is the Catskill Mountain House Hotel, which became 19th-century America’s finest resort and the birthplace of all Catskills culture, including the Hudson River School. Above it is South Mountain, and beyond, mostly out of sight, is Kaaterskill Clove — a scenic wonder and key site for the movement. (The word “clove” bewilders some people today; in this context it is not an herb, but rather a chasm that has been cleaved by Nature.)

There is something else happening here. When we, as geologists, stand on Sunset Rock, it becomes 25,000 years ago. We look left into the Hudson River Valley and see it filling with a great glacier, moving south very slowly. The ice rubs up against the Wall of Manitou, which Cole portrayed just to the left of the hotel. The glacier’s grinding motions are carving this centerpiece of Catskills scenery, including the ledge on which the hotel would someday stand. As we watch, the ice swells up below us, crosses the ledge, and spreads to the right and toward the west. Its abrasive motions carve the basin of North Lake that Cole painted. From Sunset Rock, we have “witnessed” glaciers creating a famous Catskills landscape.

Next, the Art Trail guide pointed us to Site 5, the top of Kaaterskill Falls. Cole came here in 1825 and produced one of the first Hudson River School paintings (Fig. 5). We explored a bit and found the very ledge where he must have sat as he sketched. A bit awed, we took turns sitting there and took our own photograph (Fig. 6). But there was more: we stepped forward a few feet and gazed beyond the lip of the falls. Again, we had entered the Ice Age. A glacier was advancing up the clove below us. The same ice we had just seen from Sunset Rock was now rising up Kaaterskill Clove, pushed from behind. It was sculpting the very landscape that Cole would later paint. We watched with fascination, beginning to understand that it was ice that created so much of this scenery.

We then found our way to Site 6 and beheld the modern-day view of Cole’s “Lake with Dead Trees” (Fig. 7). Cole had also sketched this place in 1825, but, once again, “we were there” during the Ice Age. Advancing toward us, that same Kaaterskill Falls glacier was grinding its way into the local bedrock. This powerful force was scouring out the South Lake basin (Fig. 8) that Cole would paint.

A visit to Site 4 would reveal more. There Cole made another of his early views, this one looking down Kaaterskill Clove (Fig. 9). Five miles long, a mile across, and a thousand feet deep, this chasm would lure future generations of landscapists, but Cole got there first. Kaaterskill Clove truly merits the adjective “awesome” — too grand to be compressed into one artistic view. Perhaps that’s why Cole chose to paint only its narrow upstream end.

We took a hiking trail out along the clove’s north rim, unexpectedly journeying 15,000 years back in time. Standing on Inspiration Point (Fig. 10), below us we could see the clove filled with ice, a lower part of that same Kaaterskill Falls glacier. But now the climate had warmed; this ice was melting. We could hear the powerful subglacial flow of meltwater, muffled far beneath its icy surface. Down there, that torrent was cutting through the glacier and into the clove’s bedrock bottom. It was carving the deep, narrow canyon that has beckoned generations of painters.

Site 5 relates to what is perhaps Cole’s most famous painting, which depicts Kaaterskill Falls from below (Fig. 11). This is another of the early scenes that launched his career. He eliminated all evidence of the modern tourist industry, painting it instead as his prehistoric Sublime. A single Native American stands atop the lower falls surveying the scene.

We found our way to the bottom of the falls on a foggy day and looked into the past (Fig. 12). For us the Ice Age was just ending. Down the canyon, there was still a glacier, but above us enormous amounts of the remaining ice were quickly melting. Raging, foaming, pounding, thundering torrents were cascading over the top of Kaaterskill Falls. The sound was unbelievable and made worse by its echoing off the cliffs all around. It seems we had picked the most violent day in the history of the falls. Never before had so much water passed across it; never again would there be this much. We were watching the Sublime origins of Kaaterskill Falls.

New Perspectives

How much did Thomas Cole know of all this? Perhaps more than one might assume. Cole made the acquaintance of several accomplished geologists, the most notable being the Yale professor Benjamin Silliman. The theory of the Ice Age had just been born in the 1820s, so surely Cole was familiar with it. He could not have known the full extent to which glaciers had created his beloved landscapes, but he almost certainly knew they had been there.

For us, it had been quite the adventure. We had explored Thomas Cole’s Catskills realm and discovered something fundamental about the Sublime. We had always known that our beautiful Catskills had inspired much great art in the 19th century, but now we had looked deeper back in time. The Hudson River School artists painted these landscapes, but first the glaciers had sculpted them. Ultimately, both the landscapes and the paintings are gifts of the Ice Age.

***

ROBERT TITUS, PHD and JOHANNA TITUS are popular science writers, focusing on the geological history of the Catskills. They have authored The Catskills in the Ice Age (3rd edition, 2019, Purple Mountain Press and Black Dome Press). They can be contacted at [email protected]. Robert Titus took all of the modern photographs illustrated here, and the authors have sourced several of the historical images through Wikimedia Commons.

Information: Cedar Grove: thomascole.org; Mountain Top Historical Society: mths.org.

Really great and informative article! Thank you!