Many family road trips in the 1960s involved stopping at natural attractions or visiting grandparents, taking in a small-town carnival or reaching a lakeside cabin for a stay. For Elizabeth Goldstein, they meant piling into the car with her parents and sister and driving from their home in the Bronx to other cities to see Rembrandts and Goyas, Picassos and Mondrians.

“I come from an itinerant family always in search of art,” says Goldstein, who serves as president of New York’s Municipal Art Society (MAS), the influential nonprofit that advocates for preservation of the city’s built and natural environments. Goldstein recalls one of her earliest memories of such driving expeditions. “My parents had stopped at the Munson museum [in Utica, New York], and, as a 4- or 5-year-old, I remember playing in the children’s room there as they went off to look at art.”

Most of the time, though, Goldstein and her sister went hand-in-hand with their parents through museum galleries in New York and other American cities. “For one of my father’s sabbaticals, he took my sister and me out of school when I was 13, and we all went to Europe to see art. For three months, we looked at art in Amsterdam, Brussels, Rome, Florence.”

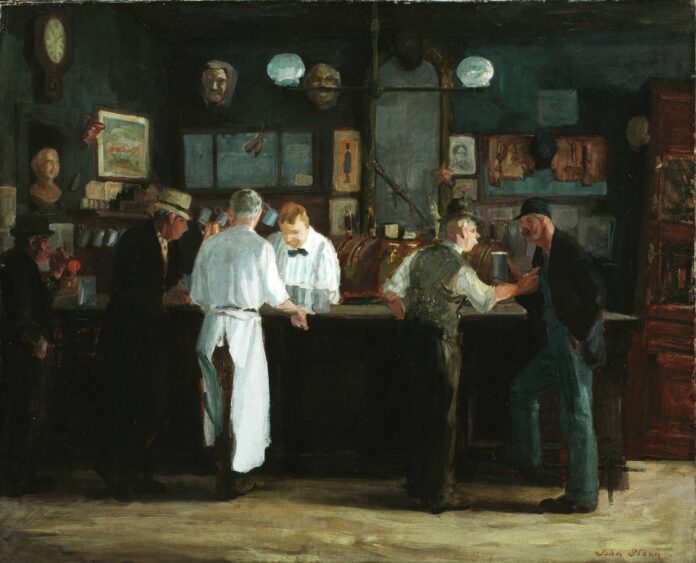

But it was on a girlhood visit to the Whitney Museum of American Art with her grandmother that Goldstein recalls seeing her first John Sloan painting, “Backyards, Greenwich Village” (1914), an iconic depiction of a snowy streetscape with children building a snowman and a black cat frolicking in the drifts. “It’s why I also love this painting so much,” says Goldstein, referring to Sloan’s “McSorley’s Bar.”

“But why does it have to be in the Detroit Institute of Arts [DIA] instead of in New York?” she asks with mock outrage, acknowledging that the venerable Manhattan bar still exists on East 7th Street, where it has been a presence since the 1850s.

Goldstein notes, “I am a big fan of Dutch art, and so I think I’m drawn to dark atmospheric canvases in general. Of course I know McSorley’s, but the first time I saw this painting in a traveling exhibition, I didn’t recognize it as the bar. When I looked at the label and realized it was McSorley’s, a light bulb went off.”

Though Goldstein has also seen the work in situ at the DIA, she continues to look at images of it. “My grandmother owned a couple of Ashcan School paintings by a minor artist, and I was so intrigued by what the artists depicted that I’ve been collecting books and catalogues about that group ever since.”

While McSorley’s continues to serve patrons, and looks much — in its appealing, ramshackle way — as it has for nearly 170 years, Goldstein points out that the barkeeps no longer wear aprons quite as long as those in the painting. “The bar’s age is definitely part of its attraction, and you can tell there’s been a lot of cigarette smoking in there, a lot of whiskey splashed on the bar, and a lot of beer soaked up by sawdust on the floor. Sloan captured a place where you can still go, an example of a wonderful aspect of New York. And in my role at the MAS, I’ve become very interested in legacy businesses like McSorley’s.”

McSorley’s third-generation owner, the late Matty Maher, an Irish immigrant who died in 2020, oversaw during his long tenure one of the bar’s major social changes — the admission of women. Up until 1970, the bar’s slogan read: “Good Ale, Raw Onions, and No Ladies.” When a gender discrimination lawsuit changed that policy, women were allowed to pony up to the bar, although a women’s restroom wasn’t installed until 1986. “Of course that old policy bothered me,” says Goldstein, “but by 1975 I was old enough to begin wandering the East Village by myself, and I came upon the place. By college, I was able to venture inside. Now, there’s a long line down the block to get in.”

She concludes, “The reason this painting remains a little jewel to me is because Sloan was a master of configuring the atmosphere of a place. You can feel the sawdust underfoot just looking at it — and you can still feel the real thing by going inside.”