In this occasional series, Fine Art Today delves into the world of portraiture, highlighting historical and contemporary examples of superb quality and skill. This week we look at one of John Singer Sargent’s most well-known paintings.

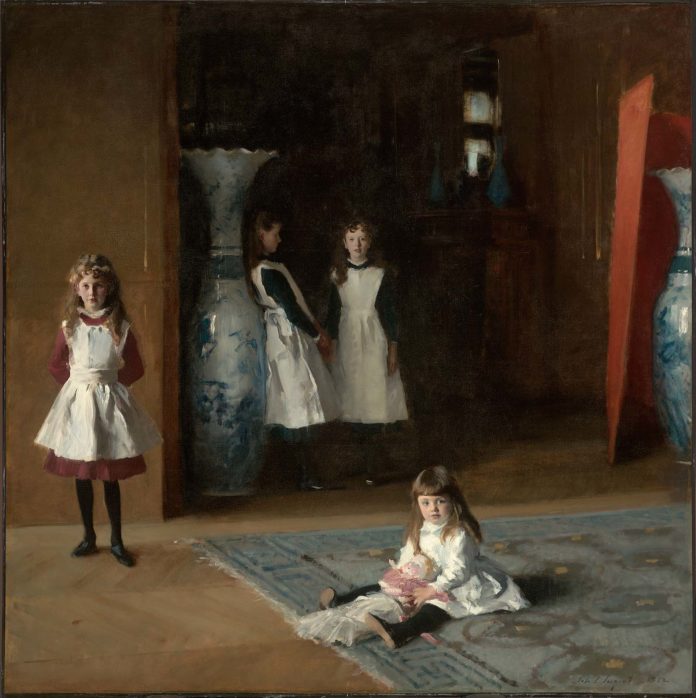

The grand foyer of Edward and Mary Boit’s luxurious home on the avenue de Friedland in Paris was the setting for a magnificent group portrait by the American expatriate John Singer Sargent in the autumn of 1882. In a shadowy setting, Sargent has delicately placed the couple’s four daughters — Mary Louisa, Florence, Jane, and Julia — in a rather odd arrangement. “While Ned and Isa may have initially approached Sargent to make a traditional portrait, they supported his ambition to create something more unusual, a painting that is half a portrait and half an interior scene,” Erica Hirshler of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston writes.

“Each of the girls is presented individually, but the features of two are obscured, an attribute antithetical to conventional portraiture and one that, combined with the lack of connection between the girls, stymied critics when the painting was first displayed. Its unusual format was inspired by the art of both the past and the present, a characteristic approach that Sargent employed to make paintings that seemed simultaneously traditional and modern. The historical precedent for the Boit portrait can be found in the work of the seventeenth-century Spanish master Diego Velázquez, an artist greatly admired in nineteenth-century France. Sargent had traveled to Madrid in 1879 to make copies after Velázquez at the Museo Nacional del Prado; among the paintings he studied was ‘Las Meninas’ (about 1656), a large and famous portrait of the young Spanish infanta with her maids in a great shadowed room. Sargent adapted Velázquez’s mysterious space, his dark subdued palette, and the manner in which his self-possessed princess directly confronts the viewer. At the same time, Sargent must have been thinking of the unusual portraits and oddly centrifugal compositions of his French contemporary Edgar Degas. ‘The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit’ shares some of Degas’s strategies: the asymmetrical composition with an almost empty center, the sense of disconnection between family members, and a feeling of modern life interrupted.

“Sargent placed the Boit girls in an indeterminate space — the entrance hall, neither entirely public nor entirely private — that is brightly lit in the foreground but recedes into a vaguely defined drawing room half-lit with mirrors and reflections. The two tall Japanese vases, made in Arita in the late nineteenth century specifically for export to the West, were prized family possessions; their unusual size in relation to the girls makes the interior seem strange and magical. The sisters are dressed almost alike, in the sort of casual clothes they would have worn in the schoolroom or at play. Their white pinafores gave Sargent an opportunity to demonstrate his mastery at painting white in different conditions of light. Only the youngest girl, Julia, engages the viewer, while the older girls recede progressively into the shadows, becoming increasingly indistinct.

“Sargent titled the painting ‘Portraits of Children’ and displayed it in December 1882 in an exhibition at the gallery of the French dealer Georges Petit, who specialized in works by an international group of artists who were more modern than many of the painters who showed at the Salon, but less innovative than the Impressionists. The picture received generally good reviews, and Sargent decided to display it again the following spring, this time at the Salon, the annual state-run exhibition in Paris that was an important venue for artists seeking to build their reputations. While some critics praised Sargent’s technical abilities, most found the composition troubling for its unconventional approach to portraiture. One unidentified writer even described it as ‘four corners and a void.’ While some have interpreted Sargent’s strategy as a poignant comment on the fickle nature of childhood and adolescence, writer Henry James, a friend of both the Boits and Sargent, described the picture as a ‘happy play-world of a family of charming children.’ With this painting, Sargent masterfully transcended portraiture, providing a continuously evocative meditation on openness and enigma, public and private, light and shadow.”

To learn more, visit the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

This article was featured in Fine Art Today, a weekly e-newsletter from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine. To start receiving Fine Art Today for free, click here.