Though you look at this 16th-century drawing, can you ever see what’s really there?

By David Masello

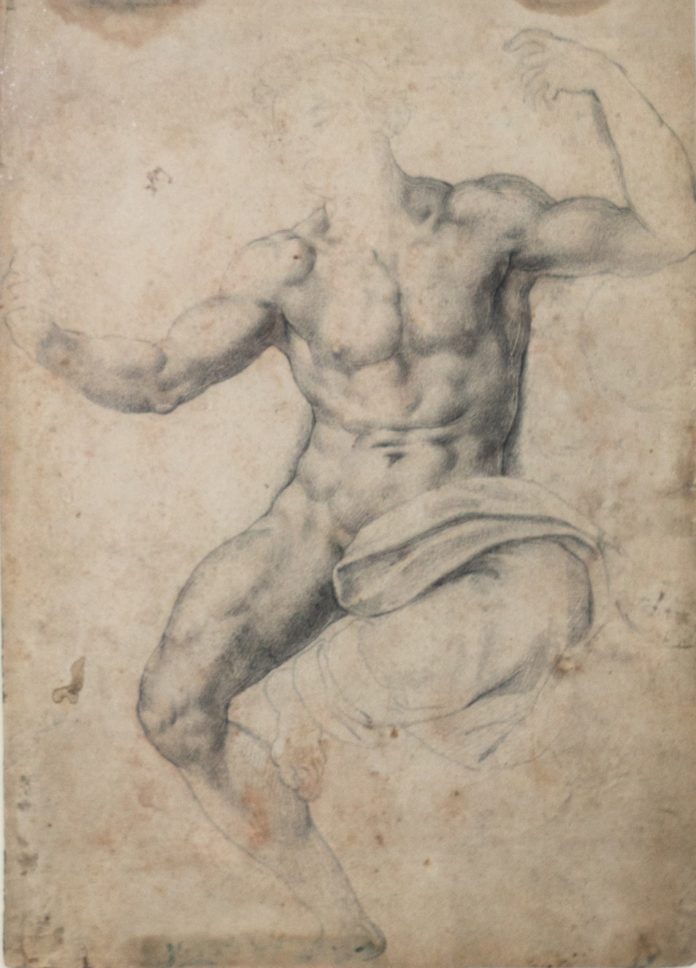

Jonathan Galassi’s favorite work of art hangs in his New York City living room, and, though he looks at this drawing every day, he never sees what’s really there. No one can. “That’s part of the beauty of it for me, that the work never got finished,” says Galassi, who has been the president and publisher of Farrar, Straus & Giroux for more than 30 years, as well as a major poet and translator of works by Montale, Leopardi, and Primo Levi. It’s the fact that this pencil drawing on paper (by an unknown 16th-century Italian artist) remains incomplete that makes it possible for him — and any other viewer — to imagine its central figure whole.

“The male figure is in the process of becoming, rather than realized,” Galassi emphasizes. He likens the effect to Michelangelo’s unfinished sculptures of slaves, in which the figures are seen to be emerging from the stone, but not completely so. Nonetheless, enough is seen to make them powerful. “This work suggests so much. I find it incredibly sensual and full of potential — like a sculpture coming out of the marble.”

Galassi, who admits to liking “all things Italian,” owns notable prints by Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Luigi Rossini, some 19th-century photographs of Venice and Tivoli, and a somewhat kitschy yet evocative Neapolitan tourist painting of Vesuvius, but nothing else of this caliber. “The drawing was given to me about five years ago by a friend, whose father had an extensive collection of mostly Northern European drawings; this was the sole Italian work,” he explains. “One evening, over dinner, he reached under the table and handed it to me, in its period frame. It was an incredible, wonderful, thoughtful present. I have paintings and drawings and various objects, but nothing this old, nothing this beautiful.”

Recognizing that the drawing of the muscular, well-defined male torso was decidedly Mannerist in style, Galassi showed it to a curator friend at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “She said that it is likely a Northern Italian work. She could tell this by the rendering of the feet, or, in this case, foot, since only one is finished. I’m not sure how a foot might reveal that difference, but she loved the work, too, and recognized its merits.”

Works that are unfinished inspire conjecture. “The possibilities of this figure and why it was never completed are intensified by the fact that you don’t see a face,” says Galassi. “Who knows, maybe if the face were in place, it would be a disappointing one!” In his daily perusal of the drawing, situated now beside his fireplace, Galassi keeps seeing new details — the heavily penciled lines of the torso’s sides that make the figure stand out as if bracketed, the modest drape of the towel down to the floor, the ghosting of a head. And Galassi is always coming up with new theories as to why the artist left the drawing in this state. “Maybe there was something wrong about it in his view,” he asks rhetorically. “Is the figure dancing? Was he to be shown playing an instrument, as the position of his arms and hands seems to suggest?”

So, as in some of Galassi’s own poetry, and in the poetry he translates, a state of ambiguity characterizes this drawing. “It doesn’t frustrate me that it’s not finished,” he says. “I accept it for what it is, a beautiful figure in a constant motion of emergence.”

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

The other appeal of this drawing, at least for me, is the antiquity of it, and the fact that artists in the pre-industrial age had nothing to lean on except their talent, and whatever tools they could gather. What they themselves were created to be they became; no artificial assistance from technology, or supplements to their diet, and nothing beyond their innate skill to render art like this. You can feel the power of the artist regardless of the subject.