Contemporary artist Andrew Denman on finding a place for fine art in a digital world.

Editor’s Note: Visit a two-person exhibition featuring new paintings by Andrew Denman (“Between the Lines”) and new sculptures by Don Rambadt (“Uncut”) at Astoria Fine Art, Jackson Hole, WY, August 1-10, 2019.

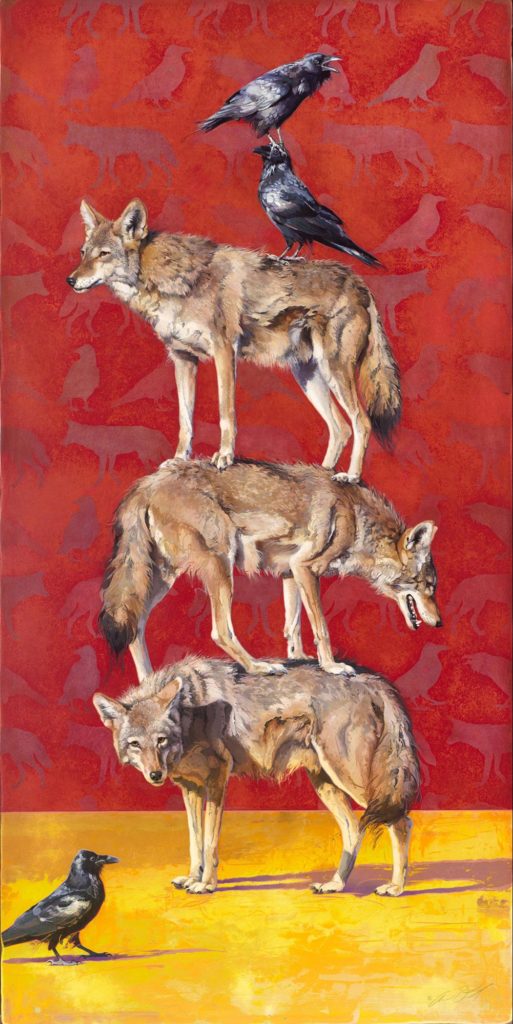

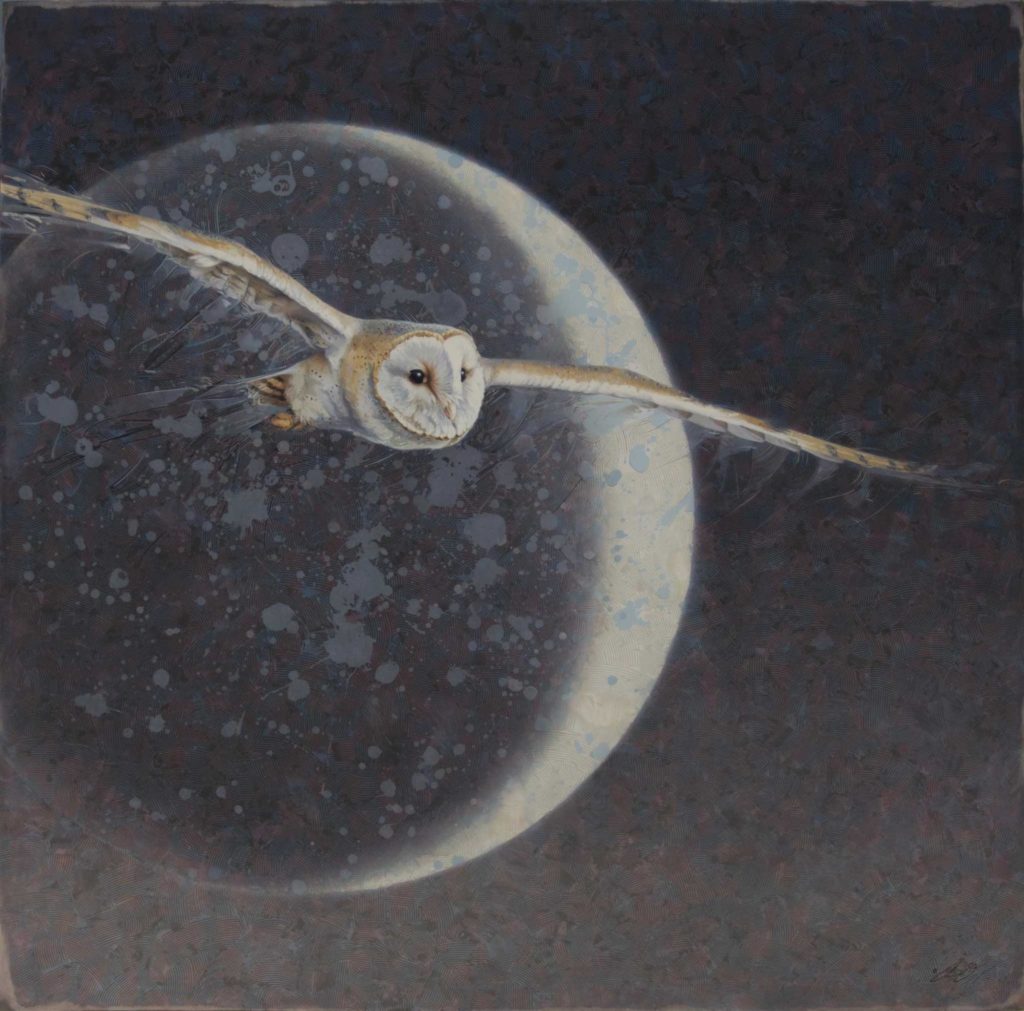

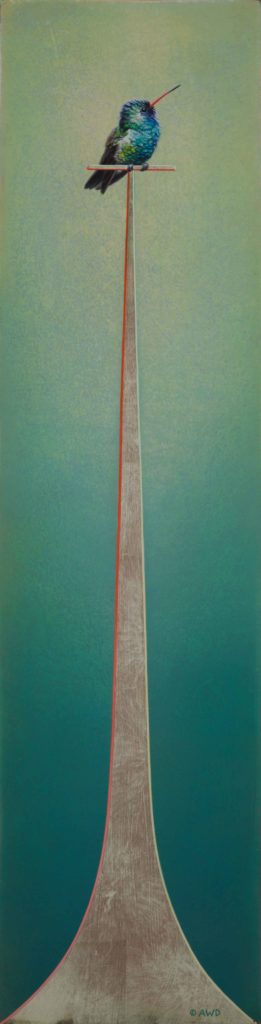

About the Show: Denman will focus on his ongoing “Totem Series,” whimsical and thought-provoking pieces featuring birds and animals arranged in precarious towers, and his new “String Theory Series,” which focuses on birds interacting with abstract shapes, lines, and vibrant color fields. Don’s new body of work, “Uncut,” will explore a rawer, more spontaneous approach to his work. While these sculptures will still capture the stylized, open forms we have come to expect, the artist is challenging himself to compose the works using only cut-offs and “scraps” from his other projects, with a bare minimum of manipulation and editing.

The Porcupine and The Mona Lisa

By Andrew Denman

When I get together with my artist friends, it is a rare opportunity to talk shop — and talk we do. Most of it is an endless stream of complaints and reassurances, kvetching away about the trials and tribulations of a life behind the easel, in the studio, at the foundry, or in the gallery.

Among those topics we discuss is a growing sense of dis-ease, a fear that having committed ourselves to the ancient art of applying colored goo to a substrate or pushing about wax or clay with nothing but our hands, eyes, and imaginations to guide us, we may not be able to adapt to a changing world.

Websites that sell digital wall-frames and Netflix-like subscription services with rotating images of paintings by old masters leave many of us fearing that our kind of art might not have a place in the digital age.

Young artists producing beautiful drawings on their Wacom Tablets without ever setting pencil to paper only add to the anxiety. A generation glued to their phones, flicking through images as casually as one hunts for a ripe avocado in a grocery store bin, brings into question the future of the audience we need to make a living from our respective crafts.

There are reasons to be optimistic. Even in the midst of this Brave New World, the much parodied but unquestionably relevant hipster culture seems to be very much a rejection of the digital age; yes, hipsters have their smartphones too, but in my experience, they are also attracted to hand-crafted artisanal products, retro mechanical devices, and the feel of something real in their hands.

They are not seduced by the wholly ephemeral world of the six-second Vine video or disappearing Snapchat photo. The question is whether or not buying original art will prove to be a priority for them, the digitally immersed millennials, current teenagers and tweens, or generations yet unborn but undoubtedly soon-to-be possessed by their own unique preoccupations.

As such, and despite the inclination of most of us to simply bury ourselves in the studio and do what we do best — create art — one of the most important questions for today’s working artist to consider is this: what is the role of art in an increasingly digital world that caters to increasingly short attention spans?

It is not without a sense of irony that I ask this question here, now, in an article written specifically for a digital newsletter.

Drama and Scandals

Part of the issue is the role of artists in society; with the exception of film and music, artists are rarely at the forefront of popular culture these days. In college I was fascinated by the study of art history, especially where relationships and even scandals came into play. I recall a vivid anecdote in which, at an 1883 party, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, that great neo-classicist and distorter of female anatomy, became so unhinged while lecturing his rival, the great Romantic painter Eugene Delacroix, about the value of drawing that he spilled coffee all over himself and then stormed off in a rage.

I delighted in the story of the wonderfully weird Salvador Dali opening the 1936 International Exhibition of Surrealism in London with a speech delivered in a deep-sea diving suit to symbolize the dive into the subconscious. However conceptually brilliant the stunt, it was hardly well thought out, and the artist nearly suffocated in the helmet, which had to be removed before he passed out.

I was fascinated by Picasso’s blue, rose, and other periods, which unfold like a nakedly public tour of his life’s personal traumas, triumphs, and inconstant love affairs. Painters and sculptors once occupied, and rightly so, the same space in newspapers and scandal rags now dominated by Kardashians, Wests, and Real Housewives. Going to Art Salons and looking at paintings was once the pastime that an afternoon at the movies was 10 years ago, and that binge-watching an entire season of Game of Thrones is now.

But if fine art is no longer at the dominant forefront of popular culture, where does it live? While there are still those rare celebrity artists like Banksy or Damien Hirst that capture media attention, frankly more for their marketing than for their messages, the true celebrity artists seem to have died out with the Picassos, Dalis, and Warhols.

There is no question that art is still culturally relevant. Certainly as a commodity it continues to sell, though making a living at it is as tough a row to hoe as it ever was. Though some of us are lucky to have a few collectors who sustain us, most of us sell a lot of work — either through galleries, art brokers, booth shows, or our own studios — to a lot of people from mainly middle and upper-class households to grace the walls of private homes.

Of course there are still great pieces of public art, but even that, in challenging economic times, is hardly enough to sustain a great many artists or to drive the kind of vast, decades-long art movements that church, state, and a few powerful taste-makers once propelled. Anyone living in this so-called “art world,” even those who only seldomly emerge from the studio, and, like post-hibernation bears, blink the sun from bleary, light-starved eyes, will notice a changed and changing landscape.

For my own part, I have always tried to keep in touch with what is happening in the art world around me by thumbing through art magazines, perusing the posts of artsy Facebook friends over a zealously clutched mug of morning coffee, attending gallery openings when time permits, and visiting museums when a show of note tours nearby or when travel takes me within range of a tantalizing venue. In the case of public venues, I often spend almost as much time observing how other people interact with the art as I do observing the art myself.

A case in point: I recently attended a Rene Magritte retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). Although I was heartened to see so many young people at the show, I was finding it difficult to enjoy the art with the constant intrusion of smartphones thrust in front of the work (and me) to snap a photo of the paintings. I observed several young women in particular who, barely even bothering to look directly at the paintings, seemed intent on capturing a cell phone photo of every piece in the show. I don’t object to the desire to try and record an experience one finds memorable, but the fact that every painting was observed through the phone and only through the phone made me wonder what kind of experience these museum visitors were after.

It’s long been discussed that our reliance on digital technology is causing our brains to take a vacation. Our long-term memories are surrendering to search engines and “encyclopedic” websites.

Why remember the details of the Civil War, how to spell disestablishmentarianism, or how to make an empanada from scratch when all the information one needs is a click away (and can be re-visited again and again)?

I would suggest that by failing to consciously and carefully observe art (or the world around us in general), by relying on a quickly captured image to stand in for our own memories, we risk losing our ability to appreciate and absorb what we see with our own eyes.

When these museum visitors left the show, had they really seen Magritte? Would they quickly swipe through those images later, sitting with their friends at a nearby falafel restaurant or Starbucks while chatting about how bad-ass Laura Linney is in the latest season of “Ozark,” and in that context would they really appreciate the magic of Magritte’s magical realism?

Fine art is intended to force us to slow down, to appreciate both the subject and the style of the art, to form our personal interpretations, to puzzle out the artist’s intentions, and indeed to consider the relevance of something that an artist invested his or her blood, sweat, and tears to create. Can our fly-by, soundbite-driven popular culture be a vehicle for this kind of expression, or make room for the state of mind needed to experience it? Can the long and steady contemplation of a painting compete with the dopamine rush of the swipe and click? Or is it not a matter of competition at all, simply a technologically driven change in the manner in which we experience art?

These are questions worth asking, and came into particular focus for me last year when I realized a lifelong dream with a visit to Paris. My partner and I stayed at a modest hotel well-located within walking distance of both Notre Dame and the Louvre. On the afternoon of our arrival, we walked along the River Seine as the sun set, dazzling the dark water with ingots of shifting gold.

We arrived at the Cathedral just as the last light of day painted its gargoyle-festooned façade with tangerine light, throwing long, lavender shadows across the ancient stone. It was a nearly religious moment for me that brought me back to childhood fascinations long-overshadowed by life’s necessities, and I cried like a baby.

The next day I finally came face to face (so to speak) with “Nike of Samothrace,” so proud and commanding, even despite — and perhaps because of — her lack of arms or a head, at the top the Daru staircase in the Louvre’s Denon wing. A thoughtless tourist who tried to tie his shoe on her plinth was suitably excoriated by a Parisian Art lover. “This is a piece of art!” she thundered, and shooed him away like a particularly large and troublesome gnat. “Bravo,” I cheered inwardly.

Not everyone has the sensitivity to appreciate truly great art, but then even someone like myself, predisposed to the task, can find the Louvre overwhelming to the point of numbness.

A professor of mine once admonished his students never to spend too much time looking at great art, lest we become too fearful to ever paint anything ourselves. It’s a point well-taken, especially in a place where, around every bend, one is confronted by paintings and sculpture one spent weeks dissecting in an art history class.

I felt guilty spending so little time with a piece as emotionally overwhelming as Théodore Géricault’s epic “Raft of the Medusa” or Jacques-Louis David’s sprawling and vividly detailed, “The Coronation of Napoleon,” but the promise of yet more wonders drew me on.

#ParisRules

It was my experience with “The Mona Lisa” that is especially relevant to this discussion. In all honesty, I have never been a huge fan of “The Mona Lisa,” agreeing with an old college professor of mine who referred to it as “the most over-rated painting in history,” but I wasn’t about to leave without at least paying her a visit. Sadly, she was obscured by a bristling ball of selfie sticks wielded by perhaps more than a hundred tourists, shifting and seething like some enormous, half-formed sea urchin or porcupine.

Surely their enthusiasm over encountering this famous painting was understandable, but to my horror,few of them were actually looking at it. Most people were, as at the Magritte exhibit, viewing her through their phones. Others, however, were actually facing their cell phone cameras, and the painting was a mere backdrop to their duck-lips, goofy grins, and Oh-My-Gosh-Here’s-The-Mona-Lisa faces. One woman elbowed past me, her eyes bulging and mouth agape like a gasping carp out of water.

I was not going to stand in the way of her particular homage to Leonardo, an image of herself, mugging for the camera amidst a sea of people with The Mona Lisa, ensconced behind bullet-proof glass, a velvet rope, and stern-faced security guards. The painting itself, in the background of her photo, must have seemed shrunk by distance to the size of a postage-stamp and likely unrecognizable without a caption reading something like, “Me in front of the Mona Lisa, #Louvre, #Leonardo #ParisRules.”

The painting’s long history of extreme fame was the cause of the hysteria itself, but I have to think that, prior to this age of rapid-fire digital imagery, museum visitors excited over their brush with greatness and eager to lord the experience over others would actually have had to observe the painting in order to be able to convincingly recount that they had “been there and done that.” That’s no longer necessary, not when a half-second’s pause, a click, and an Instagram post are all that is necessary to show the world “I saw the Mona Lisa!”

Getting to Know Leonardo, Right or Wrong

I fled the room to find several vastly superior DaVinci paintings in the next gallery, most without the interference of glass, and none being observed by more than a few people.

Here was my chance to commune with Leonardo as I would like to get to know him, where I could observe every graceful line and the porcelain translucence of skin, where I could feel the love he might have had for his model, and imagine the hand that might, during a break, have dropped the charcoal or brush and rested, tenderly, on a young shoulder.

I was torn. On the one hand, an artist should celebrate the fact that an institution like the Louvre was so full of people coming to see art. As an institution it couldn’t exist without that. Who am I to judge that those visitors whom I encountered were not enjoying the art as I would have them enjoy it?

I have to give them, and the young people at the SFMOMA Magritte exhibit too, some serious kudos for actually coming to a museum at all! They could far more easily have gone to see a movie, spectated a sporting event, or stayed home to “Netflix and chill” instead.

After the death of a dear friend, a Chaplain once told me “There is no right or wrong way to grieve.” Likewise, and for all of my particularly personal and subjective feelings on the subject, there is no right or wrong way to experience art.

As an artist, I am especially excited when a collector sees in my own work the same thing that I felt when I chose to paint it. More often than not, however, a viewer will see something in my work that I didn’t intend. Such interpretations are no less relevant than mine, and in some cases are cogent enough to become a part of my own narratives after the fact.

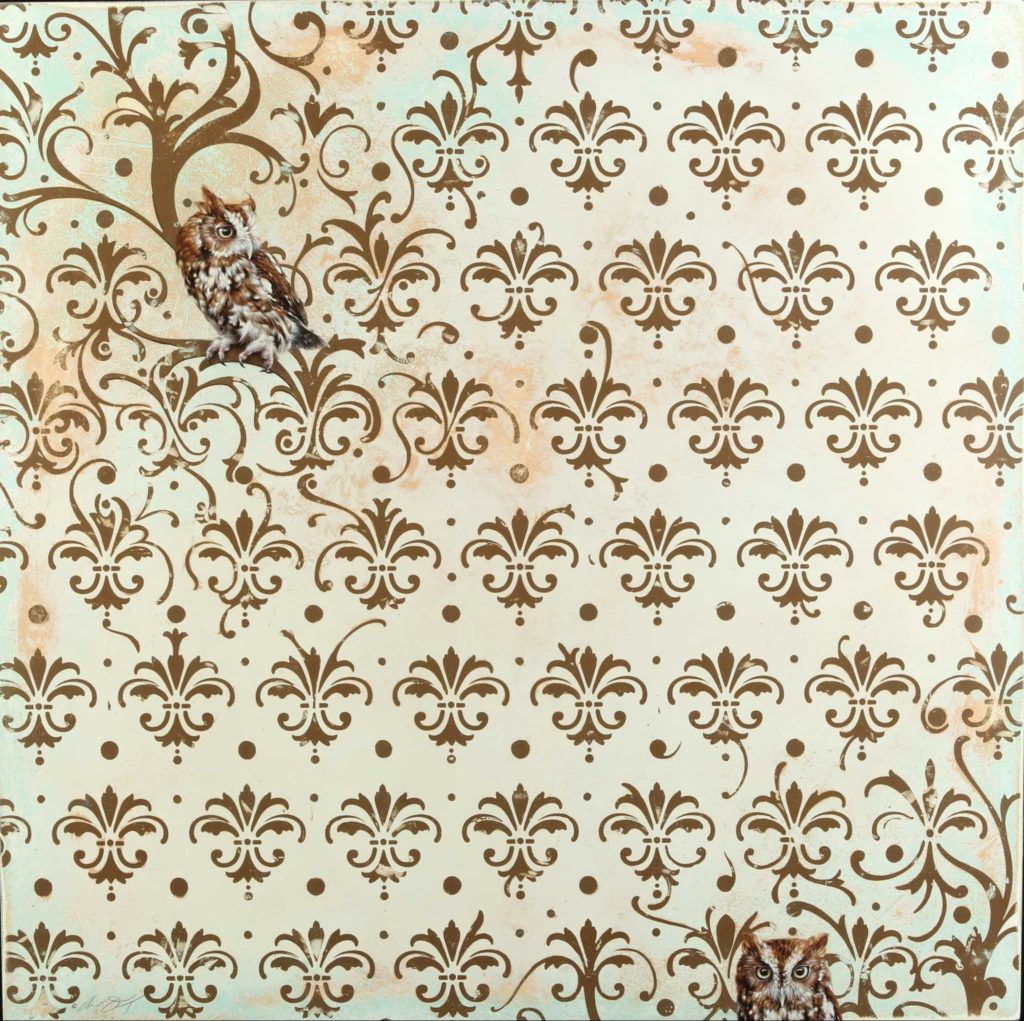

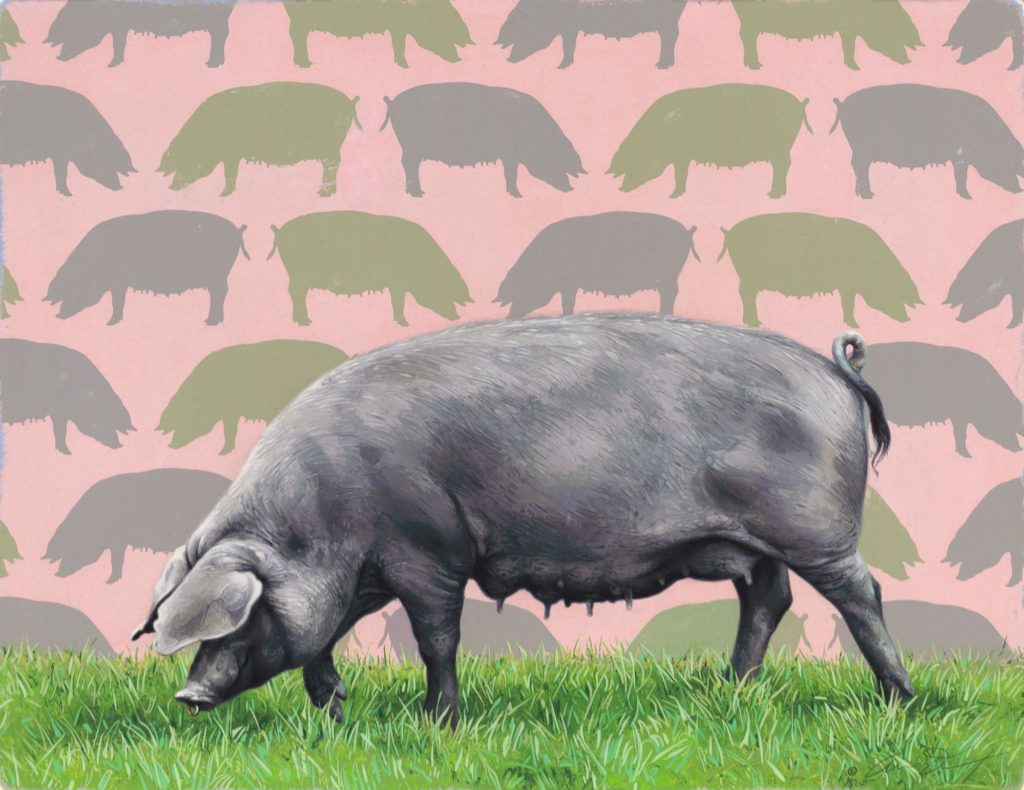

The first of my “Modern Camouflage Series,” these pieces focus on the tension between illusionistic and flat pictorial elements as well as the displacement of animals from wild to increasingly human-altered environments.

Such was the case with my “Modern Camouflage” series, modernist wildlife paintings in which owls emerge from heavily patterned, wallpaper-like backgrounds. At their core, these pieces were an exploration of the tension created between the illusionistically painted subjects and flat, decorative grounds, my visual commentary on this same over-arching conflict between differing schools of painting from the late 1800s right up until the advent of post-modernism.

A magazine writer, along with several collectors, saw them instead as commentaries on the displacement of animals from wild to urban or suburban environments as habitat destruction fuels human “advancement.” It was an idea that had not occurred to me at the time, but which, once mentioned, was so patently obvious that it has become a part of the motivation for the continuation of that series.

As a passionate conservationist, I am certain that this metaphorical interpretation of the contrast between organic and inorganic, natural and unnatural elements so integral to the “ModCam” series was, however subconsciously, a factor in its creation; it simply took a fresh pair of eyes to see what I had overlooked.

I wonder, with more than a gleam of mischief in my eye, how Leonardo DaVinci would respond to the cult status that his work, especially good old Mona, has achieved. Whether he might be bemused, amazed, heartened, disgusted, or any combination thereof really doesn’t matter.

At the very core, this is the true gift of the artist. We produce our “brain children” and send them off into the world where we want nothing more than for them to find their own way. They will always be our children, but they will, through contact with others, evolve into something other than what they were the day they left our studios. Not only is there nothing wrong with that, it is necessary.

The Internet simply provides another fertile breeding ground into which we can release our offspring to, as it were, “Go forth and multiply.” Far from being a boogie-man of ones and zeros, the digital medium is only another lens through which art will be experienced and interpreted, now and into the foreseeable future.

Content Vs. Medium Vs. Marketing

But no matter how powerful the lens, it will never, in and of itself, replace the camera. UK-based social media strategist and founder of SociActive Yasmin Valentine notes, “The digital will only ever be supported by the physical” (and vice-versa). The two must be married, must exist inextricably hand-in-hand, because one cannot exist (for the professional working artist that is) without the other.

As artists, we should not confuse what we do, which is produce content, with the medium, in this case the Internet and an increasing panoply of digital platforms therein, that have the potential to spread that content, virus-like, around the globe in exponential fashion.

I recently had a successful two-man exhibition in England with sculptor Simon Gudgeon, founder of Sculpture by the Lakes in Dorset. Even as a social media expert, Yasmin’s multi-pronged outreach for that show included distributing printed materials to select local markets, so potential new collectors could feel something solid and beautiful in the hand, because she and Simon know the value of something real.

The goal of her entire marketing strategy, including the carefully laid out campaign of social media postings, was, in fact, to get people through the door to look at paintings on the wall, to experience the art itself, not its pale digital simulacrum via Facebook or Instagram.

Of course, in addition to Yasmin’s role, we must not leave out the massive outreach by the Sculpture Park to existing collectors and visitors, relationships which, while certainly supported by email newsletters and the like, were nonetheless based on real contact, handshakes, and personal experience with the venue, its founder, and his artwork.

Yet even those efforts must be put into context, must be considered as part of a long-term strategy, even if their original focus was the timely promotion of a single event.

Artists can often be frustrated by marketing of all kinds because results are not often entirely or immediately quantifiable. Early in my career, having one’s art showcased in a feature article in a national art magazine was the end-all-be-all, not because that article necessarily brought you a torrent of new clients, but because it contributed to an overall, cumulative increase in ones bonafides. Likewise, digital media is simply another rock face to be chipped away at over time until one has a good toe-hold and can climb confidently to the next career plateau.

It is easy, and not entirely unreasonable, for an artist to look skeptically upon the fast-paced world of social media, but how many of us honestly used to pick up a magazine and read every article in full? Was not the periodical print media’s “thumb-through-it-and-toss-it-aside” ethos the “swipe-and-click” of yesteryear?

Even if art itself goes digital, that is not necessarily something to fear. There is no question that new technology has the potential to drastically change a society, including its art, but disruption is not synonymous with destruction.

Impressionism would have been entirely impossible without the invention of tube paints in 1841. By making previously unwieldy pigments and binders portable and ready-to-use, artists were finally able to work outside and truly paint the light itself. As a result, palettes changed, the application of the paint changed, and tastes in art evolved right along with those developments. Yet here we are, nearly 200 years later, and just as many artists still prefer to paint indoors in their studios as out en plein air. The disruptive technology only expanded what is possible.

The Evolution of Art

Fine artists may or may not find ways to use digital media that are just as revolutionary, but I would argue that whatever revolution comes will simply add another layer to the story of art, and it will do so without smothering any of those underlying it.

I truly believe there will always be a place for handmade art in the future. It will, like all things, wax and wane in popularity, and the people who collect it will no doubt change. But like politics, ceaselessly swinging left or right, more often in the middle than not but always trending toward one pole or another, so too it is with art and how it is appreciated.

If the fashion world has taught us anything, it is that everything that was once old will become new again. One year bare midriffs are the norm, the next — modesty is the new sexy. An artist’s challenge in this day and age is not to remain relevant by changing what he or she does to meet the perceived demands of the moment (that is a maddeningly slippery eel to chase). Rather we must remain visible by taking advantage of a whole new world of media to access collectors and make our voices heard.

Our work can take on a new life in social media, video, and a host of formats. But ultimately, the value of what we artists are selling is, like all things, dictated by scarcity. Rather than being frightened by the emphasis on the fleeting, experiential world around us, we should take the opportunity to set ourselves apart, to declare that our value in this shifting landscape is dictated precisely by the painstaking manner in which our work is produced, and the simple fact that everything we do, is in fact, one-of-a-kind.

Moreover, however one may feel personally about the digital revolution and its various manifestations, it is very much an inextricable part of our zeitgeist and, as such, a perfectly valid source for our own artistic inspiration and commentary. Part of what makes art history so engaging is that one can see how creative people responded to the events and attitudes surrounding them at any number of extraordinary junctures in history.

Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” was a direct response to the 1937 Nazi bombing of the Basque town, and it remains one of the most powerful anti-war paintings of all time. But even art that isn’t trying to be political is still a reflection of its day; certainly, the pop art movement of the fifties could not have evolved out of anything other than the post WWII prosperity that made the kind of commercial conveniences of the day so omnipresent, popular, and ultimately mundane.

An example of my “Pattern Series,” which, in part, seeks to explore animals as they relate to popular culture, consumerism, and global commercial enterprise.

My own “Pattern Series” draws on pop art history but focuses primarily on those often taken-for-granted domestic animals, such as chickens, pigs, and sheep, that fuel multi-billion-dollar industries that feed or clothe a world full of hungry and demanding human beings.

The desire to stop and appreciate those animals that provide for us is one that would hardly have occurred to me without a lifelong immersion in an environmental movement that is very specific to my own particular moment in time. Not everyone is interested in using their art for social commentary, but whether one produces “that kind of art” or not, one cannot help but be influenced by popular culture.

Every so often I meet an artist who claims to never look at or be inspired by other artists, to be wholly original, a previously undescribed gem emerging from a vacuum of unsullied interior thought. Such artists are, without exception, facile and deluded. Artists are sponges and cannot help but be inspired by what is happening around them, and the more engaged we are in life, the richer and more relevant the art will be.

Especially today, as bombarded as all of us are by a variety of imagery and opinion, none of us can claim to be living in a bubble. Even those of us who eschew as much as possible the sensorial avalanche of digital imagery and information, are in fact, reacting to it by our very attempts to avoid it. We are living in this time, and our fears of obsolescence, however forgivable amidst the noise and haste, are not productive.

We should seize the benefits of this medium where it promises to give us a platform for our ideas, ignore it where it irrelevant to our passions and our crafts, and fight it where it threatens to overshadow that which we hold dear, most of all by subjecting it to the powerful critique of our own artists’ eyes.

As artists we have the unique privilege and burdensome task of being both the observer and the observed, of soaking up the pain and joy of the world and, hearts on sleeves, bleeding right back into that same endless river.

The great civilizations of the past left behind very little but their art and architecture. Why then, do we living artists fear that our own hard-etched mark on the world will be outpaced by transitory technologies that outpace themselves already? Technologies can and do fade, but art is eternal. When Hippocrates noted that “life is short and art long” he was writing about the long period of time required to develop a great skill, versus the very short period of time one has to employ those skills before death, but in the context of this essay, I mean to imply that, short though an artist’s life may be, fine art has the power to outlast it.

Visit any museum or gallery, look past the cell phones, and see the long and storied chain that is the art historical continuum. Imagine for a moment your own place, your own link, in that great chain. Every time you finish a new painting and share it with the world, you are making your own link thicker, stronger, and harder to ignore, and, like it or not, each “like” on Facebook and each “Share” on Instagram ever-so-slightly tempers the metal.

About the Artist

Known for his unique hallmark style combining elements of realism, stylization and abstraction, Andrew Denman is at the forefront of an artistic vanguard of the best contemporary wildlife and animal painters working today.

Born in California in 1978, Denman exhibited an early fascination for art and nature. He began teaching art at just 13 years of age, and by 16, he was exhibiting at Pacific Wildlife Galleries in Lafayette, CA, at the time one of the top commercial galleries for nature-inspired artwork in the world. A BFA from Saint Mary’s College in Moraga, CA, further fueled his love of art and art history and helped transform his passion into a career. Early exhibitions almost immediately following his college graduation quickly cemented Denman’s reputation as a noteworthy new talent and attracted feature coverage in a wealth of national and international publications.

Since then, Denman’s work has toured nationally with “Andrew Denman: The Modern Wild,” a solo retrospective show curated and directed by Dr. David J. Wagner, the highly regarded “Birds in Art” exhibition, and the Society of Animal Artists, which has thrice honored Andrew’s work with Awards of Excellence. The artist is a regular participant in the Western Visions Exhibition at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, WY, an institution that named him the Lanford Monroe Memorial Artist in Residence for Winter of 2009. Denman’s work can be found in the collections of the National Museum of Wildlife Art, The Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum, WI, the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, AZ, the Nature in Art Museum, Gloucester, England, and numerous private collections around the world. The artist maintains Denman Studios at his California home, which he shares with partner and fellow artist Guy Combes.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.