While the team at Fine Art Today is doing our best to give you up-to-date information about current art shows, please also check with the individual gallery or museum to confirm that the information has not changed since it was published here.

“Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin” at Watts Gallery (Surrey, UK) examines the legacy of one of the most influential thinkers of the 19th century, as an artist, social reformer, ecological thinker, and educator.

In addition to a core group of Ruskin’s drawings and publications, the exhibition features works by J. M. W. Turner, John Everett Millais, Edward Burne-Jones, and other leading artists of the 19th century, many of which have rarely been exhibited in the United Kingdom before.

More from the gallery:

Travelling to Watts Gallery from the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA), New Haven, this object-rich exhibition features paintings, drawings, rare books, and manuscripts from the collections at the YCBA, Yale University Library, and Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A complex and often contradictory figure, John Ruskin (1819–1900) is recognized as one of the greatest art writers in the English language. He offered new insights into Gothic architecture, passionately advocated for the landscape paintings of J. M. W. Turner, and vigorously supported the Pre-Raphaelites. Ruskin believed that art had the power to transform society and that nature inspired the most meaningful art. However, at the same time he was a true Victorian polymath—a complicated figure equally uncompromising and fluent on a range of topics extending from the aesthetic realm to social reform, theology, and ecology.

The exhibition begins with works from Ruskin’s precocious childhood and teenage years, including a lively volume of juvenilia from the Beinecke Library. Ruskin’s lifelong interest in J. M. W. Turner was sparked in these early years. “Unto This Last” features Turner’s watercolor Lake Geneva and Mount Blanc (1802–05) and the oil Port Ruysdael (1826–27).

Ruskin’s Modern Painters I (1843), published when he was 24 years old, was a treatise on landscape painting with a defense of Turner at its core. In this seminal work, he advised young artists to “go to Nature in all singleness of heart [. . .] rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing.”

The intricate watercolor “Study of an Oak Leaf” (date unknown) demonstrates Ruskin’s theory that “if you can paint one leaf, you can paint the world.”

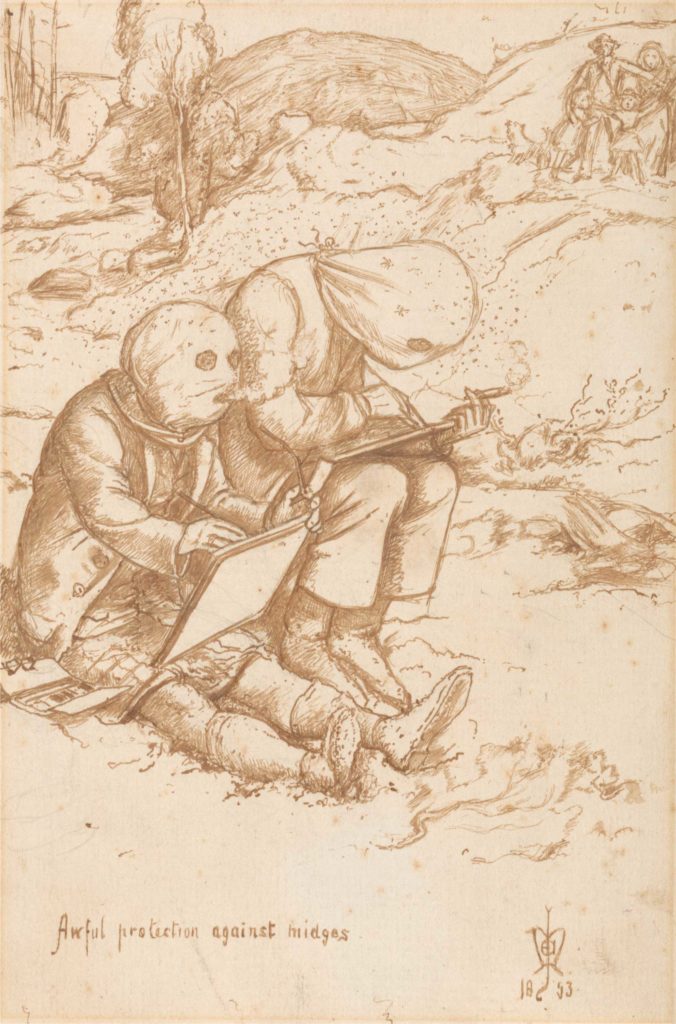

Ruskin’s closely-observational landscapes, such as “The Rocky Bank of a River” (ca. 1853), capture the vitality of nature, but drawing outdoors came with its pitfalls: On a sketching holiday with Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais drew a caricature illustrating two artists struggling with clouds of biting midges (1853).

Over the course of his lifetime, Ruskin saw industrialization, consumerism, and tourism radically alter the dramatic landscapes he loved. While many of Ruskin’s contemporaries saw the natural world as an inexhaustible stockpile of resources, he sensed humanity’s threat to the environment, foreshadowing present-day apprehension of climate catastrophe in his text “The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century.”

Ruskin saw education as a tool for reshaping society and was adamant that his lessons should be widely accessible across boundaries of class, gender, and age. Ruskin regularly brought objects from his own collections into his lessons and donated art, minerals, and rare books to schools and museums across Britain.

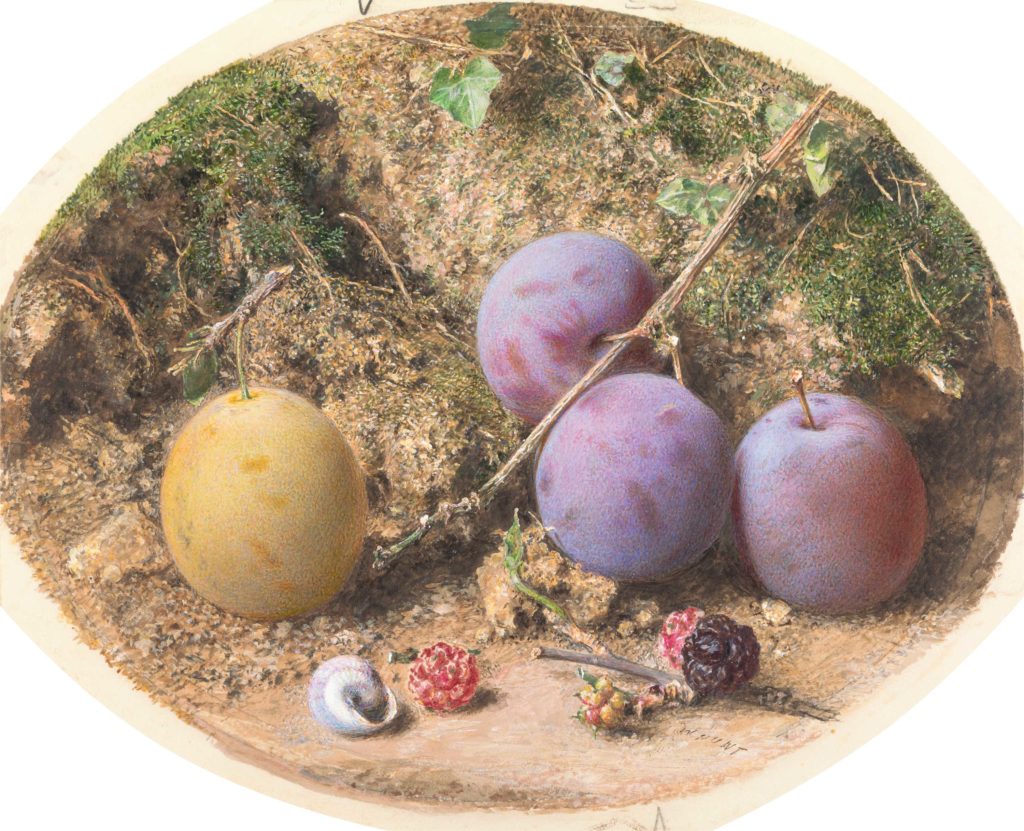

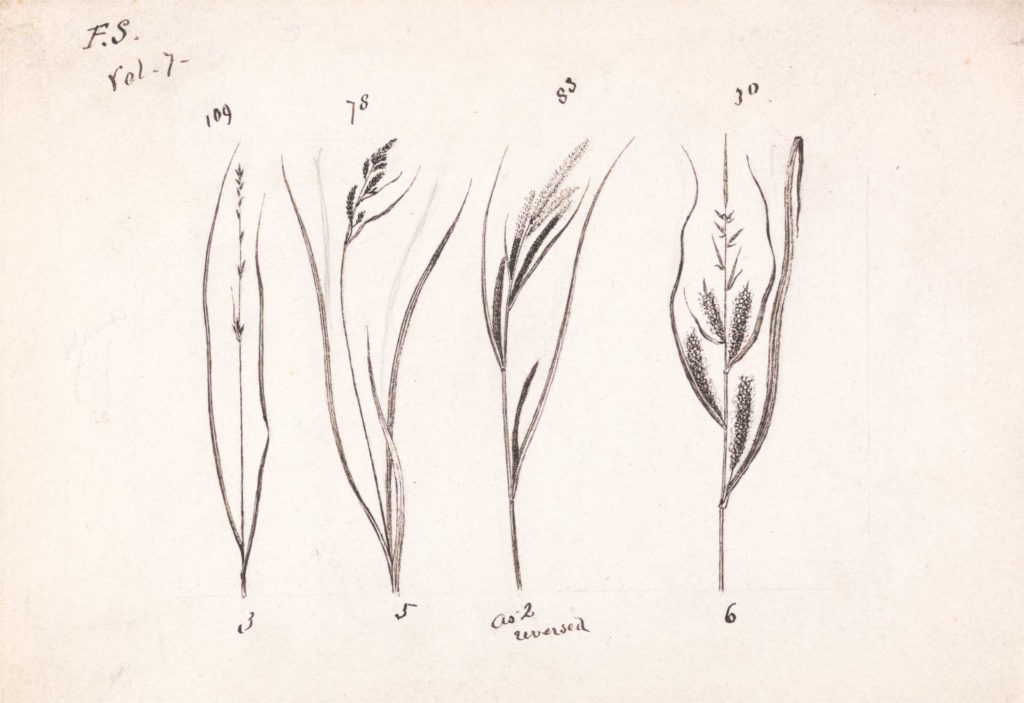

The exhibition features Edward Burne-Jones’s finished watercolor “Cupid and Psyche” (1870); Ruskin owned an earlier version of this exquisite composition and donated it to Oxford University as part of collection to be used for teaching. He advised students to study works by William Henry Hunt, such as the delicate “Plums and Mulberries” (ca. 1860). Ruskin’s teaching and writing unified art and science, as can be seen in his own attentive sketch “Four Species of Grasses” (date unknown).

Ruskin visited major manufacturing towns and lectured on the “two paths” open to society: soulless industrialization or a utopian return to traditional craft practices. Yet his solutions to society’s problems were often rooted in 19th-century assumptions about race, gender, and class that are outmoded and inappropriate today. While his writings offered a radical critique of industrialization’s negative effects on people and the environment, they also advocated for a return to a hierarchical social order that many readers then and now have rightly rejected.

Progressive thinkers worldwide, from the founders of Britain’s Labour Party to Mahatma Gandhi, have acknowledged the influence of Ruskin. His aesthetic, social, and political theories spread globally, to the United States, Japan, Russia, and India. He has inspired generations of social, political, and economic reformers who have selectively embraced the best of his artistic, social, and environmental ideals, while rejecting those aspects of his life and work that seem archaic in the 21st century.

Ruskin’s theories continue to resonate two hundred years after his birth. His visionary text “Unto this Last,” from which the exhibition takes its title, challenged capitalism itself and demanded equal treatment for everyone, even “unto” the very last person in line, the poorest or weakest. This powerful book contains a single phrase that distills all his wisdom: “THERE IS NO WEALTH BUT LIFE.”

The exhibition concludes with important work by New York–based contemporary artist Jorge Otero-Pailos, whose luminous series The Ethics of Dust results from a sustained engagement with Ruskin’s work. His highly original process involves gently coating walls of historic buildings, such as the Doge’s Palace in Venice, or Westminster Hall in London, with latex which, when removed, bears on its surface particles of the dust gathered over centuries—the dust of time. Lit from behind, the dried latex takes on a mysterious, ineffable beauty reminiscent of 20th-century painting, while also displaying an indexical trace of the processes of history and warning of the dangers of pollution, just as Ruskin did in his time.

Cicely Robinson, Brice Chief Curator, Watts Gallery—Artists’ Village says: “This significant and nuanced exhibition challenges preconceived ideas of Ruskin and invites us to consider the ongoing relevance of his complex artistic, political, and environmental legacies today. It features as part of a dynamic programme of temporary exhibitions at Watts Gallery—Artists’ Village, dedicated to the exploration and re-evaluation of Victorian art and culture today.”

Tim Barringer, Paul Mellon Professor of the History of Art at Yale, says: “Yale’s rich collections of Ruskiniana include exquisite drawings, important literary manuscripts, and even memorabilia such as his post-bag. Many of these have never been displayed in the UK, and it is a delight that they will be seen at the Watts, a key site for Victorian culture. The exhibition and accompanying book are largely the work of three doctoral students at Yale University, who have brought fresh new insights to the study of a revered, but often misunderstood, figure, whose love of nature and suspicion of capitalism seems more relevant than ever in our age of environmental crisis.”

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> And click here to subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue