BY DANIEL GRANT

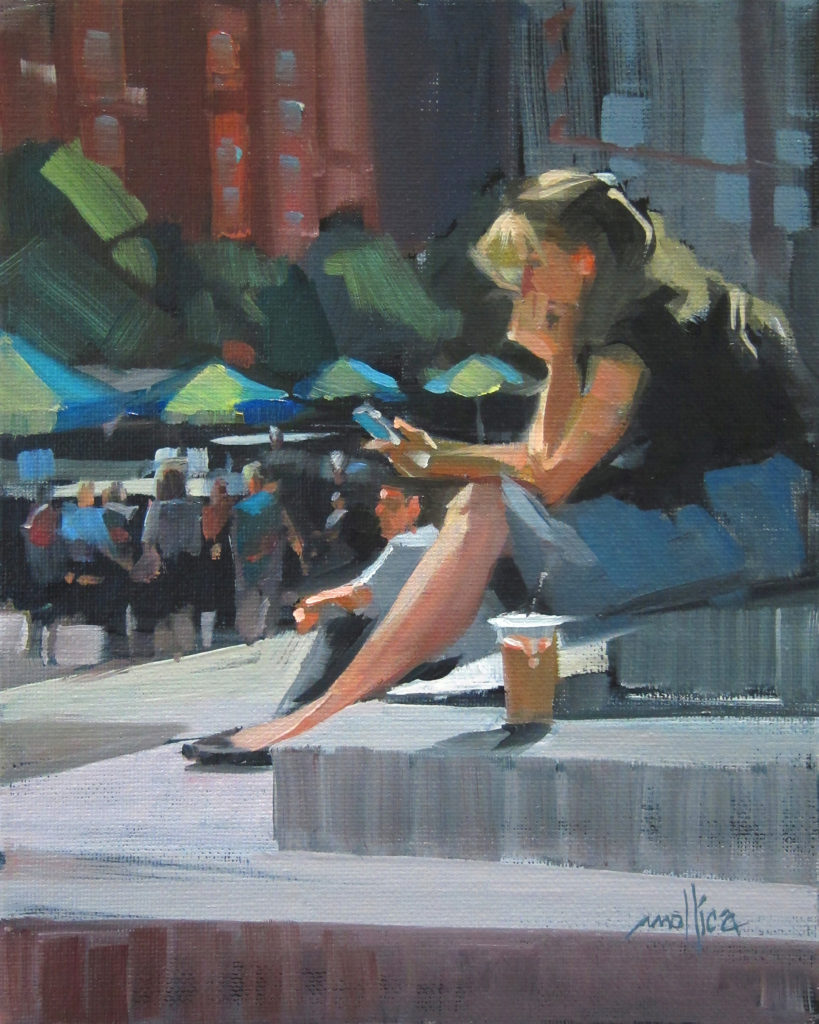

When Patti Mollica (b. 1955) graduated from art school in 1977, she was “unfocused. I didn’t know where things would lead or how to get more rooted in the art world.” OK, no real surprise there. At some point, most artists have probably said the same thing. Fortunately, Mollica is now a successful and prolific painter. Her most popular subjects are street scenes of Manhattan; she sells an average of 50 paintings annually through four galleries, as well as directly to individual collectors.

Mollica did not follow a straight line from art school to such robust sales figures. After graduating, she set up a booth at various arts festivals and did 10-minute portraits at the Great New York State Fair in her hometown of Syracuse. “From morning till evening, there was a line of people waiting for me to do their portraits,” she recalls. “I thought, there has to be an easier way to make a living than this.”

Such thoughts usually kill off a fine art career for good, but in Mollica’s case they only deferred it for a while. In 1980, she enrolled in the Atlanta-based Portfolio Center, a two-year, for-profit, non-degree-granting school that teaches copywriting, design, and illustration skills for the advertising and design fields. Mollica took to it quite well. The school awarded her the prize for best portfolio in art direction, graphic design, and illustration in her graduating class, and in 1982 she was on her way to making a living and a career in Atlanta.

For most of the 1980s and ’90s, fine art was largely an after-hours hobby for Mollica. She worked at an advertising agency for almost two years while freelancing on the side, then started freelancing full-time, working as a graphic designer and illustrator for numerous clients. Mollica created book covers for St. Martin’s Press and Penguin Press, images used in advertising campaigns for American Express, Sheraton, and Marriott, posters for New York University and Barnes & Noble, and designs for wine labels, calendars, and greeting cards. Other clients were in the technology and financial services industries.

In 1985, she joined up with a copywriter and account executive to form a creative services agency (Mollica, Bell & Dvorin) that developed advertising campaigns, identity branding, marketing strategies, graphic design, copywriting, and illustration services for corporations around the country. Its clients included hospitals, banks, shopping malls, cable providers, and accounting firms.

In 1992, after 12 years in the South, Mollica was looking to move back north; she had grown up in Syracuse and earned her B.F.A. at the State University of New York at Oswego. After relocating to Manhattan, she began her career anew, sending out her illustration and design portfolio and promptly landing numerous freelance jobs.

“I totally fell in love with the city,” Mollica explains. “The street life of people and buildings and cars and colors fit me so well.” The style of illustration and art she produced also seemed more at home in New York City than Atlanta, as her colorful brushy images of people and objects captured the bustle of Manhattan. Mollica’s new clients also liked the energetic brushwork and artistically expressive elements of her illustrations.

Many of the financial services firms liked being associated with what looked more like fine art than generic design. In fact, some of Mollica’s first exhibitions occurred at charity benefits sponsored by the hedge fund managers for whom she freelanced. “They could tell that I was an artist and not ‘just’ a designer, and they offered encouragement.”

By 2000, Mollica found her living conditions a bit cramped — “studio space is impossible to find in Manhattan, and you need some space to move around in,” she says — so she moved to Nyack, a 30-minute drive north. Other changes were taking place by then that started to shift her focus.

Most importantly, design and illustration were becoming more web-based: images were being created on computer screens rather than drafting boards and easels. “I didn’t want to give up paint,” Mollica says. “Working on a screen makes your work more sterile and left-brained.” For her, all the energy of swaths of color applied with a brush dissipated within the confines of computer code. (“I took a class in computer coding and decided that I would do anything but that.”) She felt the new web-based images were all “vector-looking. Commercial clients had hired me for my fine art look.”

So, if you want to pursue a fine art look, why not be a fine artist? That is what Mollica decided to become, without fully giving up the design and illustration jobs that still come via her agent (“only if it’s interesting and pays well”). She pushed herself to do her own paintings and get them in front of an art crowd rather than art directors.

DIFFERENT WORLDS

Having a foot in two careers such as illustration and fine art — really, anything and fine art — is not easy. The wider world often appears to demand that you choose one or the other. Tom Christopher, another full-time illustrator who became an occasional illustrator and full-time painter, notes that many art directors look down on fine artists as not working hard and being unreliable. “They have a living-in-a-cold-water-flat-and-chopping-off-your-ear conception of artists. They looked at me and said, ‘Is that what you are these days?’”

It is not an easy balance to maintain, because there is often a drop-everything aspect to commercial assignments that may disrupt the process of creating fine art, but then trade-offs feature in all creative people’s lives. Mollica’s commercial art agent, Gail Gaynin, observes that illustration is not something in which you can just dabble: you are competing for every job against very talented illustrators who do nothing but illustration all day. “A lot of people think, ‘I’m not all that busy; I can do some illustrations to make some money.’ But it doesn’t work that way,” Gaynin warns. “It’s more difficult for a fine artist to become an illustrator than for an illustrator to become a fine artist.”

Gaynin continues, “In fine art, you are working out your own ideas; in illustration you are solving someone else’s problems.” Perhaps the client isn’t just one person but a committee, maybe more than one committee — all of whom can demand changes to your concept, colors, and design. Not every fine art graduate can accommodate that. Additionally, an illustration is intended to be understood in an instant (looks cool, buy that, seems trustworthy), while a fine artwork that can be digested quickly is probably not good.

“Art should command our attention longer as we seek to comprehend what the artist is attempting to reveal. Warhol’s image of a soup can, though accurate, gives rise to a variety of thoughts — about consumerism, about billboards as the landscape of the modern world, about a familiar image drained of its original meaning — that are unrelated to a common food.

Not every agent offers the necessary latitude to an illustrator seeking to be more of a fine artist, but Gaynin can see both sides. She herself earned a B.F.A. at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn “because I had wanted to be a painter all my life.” She did not find artistic success, but a friend told her that some of her images would work as fabric designs, “so I worked up a portfolio and sent it to a company that made custom rugs,” she says. “I ended up working in that field for several years.”

Then a photographer friend asked her to act as his agent, and she doubled his volume in the first year. This eventually became her full-time career. Needless to say, it is good to be represented by someone who understands that you are multi-dimensional and that, in fact, being multi-dimensional is a selling point.

It took Mollica a while to gain a foothold in the fine art world. She approached gallery owners but learned that they “want to find you, not for you to find them.” She also “exhibited” her art in restaurants, though “some came back smelling of marinara sauce.”

Getting rejected is expected, but sometimes you just need to be at the right place at the right time. While on vacation in Provincetown, Massachusetts, Mollica stopped in at a gallery and asked the owner if she would be interested in exhibiting her work. A painter herself, Simie Maryles did not look interested, but “she asked for my card, and while I was seeking it in my bag, she began to look through my portfolio and immediately said yes.”

THE FINE ART OF SUCCESS

Simie Maryles Gallery was the first to show Mollica’s paintings. Now there are three others, and half of her sales occur through these galleries. Other sales are to people who contact her directly, and she sells smaller, less expensive paintings on Etsy.com. Her pieces range in size from 8 x 8 inches to 60 x 60 inches, priced accordingly from $225 up to $8,000. And there are private commissions from time to time.

One couple who live part of the year in Manhattan and the other part in Florida commissioned a 5 x 5-foot painting of the view from their 37th-floor apartment, which features boats on the East River, cars, pedestrians, and the United Nations building. Mollica says they “wanted to hang it in their Florida home to remind them of what they saw every day in New York.”

She has also been asked to paint portraits or a favorite vacation spot. Mollica also conducts painting workshops for amateurs in the U.S. and abroad. She has written four art instruction books and created several videos that may be purchased as DVDs or downloaded, and she gives two-hour lectures on acrylic paint as a representative of Golden Artist Colors.

Moreover, Mollica still takes on the occasional illustration job when Gail Gaynin calls. Adding it all up, Mollica now earns twice as much as a fine artist than she did as an illustrator. Piecing together a livelihood from various sources is something she had already mastered as a freelance illustrator.

“There aren’t a lot of safety nets out there,” Mollica cautions. Undoubtedly, many people see themselves as novelists or songwriters or actors or fine artists. They just need a break to let them leave their day jobs and become who they are. It does happen, and it’s more likely to happen for people who can assemble various revenue streams that provide income when one or another slows to a trickle.

The acclaimed California painter Wayne Thiebaud — still working at age 99 — calls himself an “illustrator gone uppity.” He is definitely not alone.

Connect with Patti Mollica: pattimollica.com

DANIEL GRANT is the author of The Business of Being an Artist (Skyhorse Press) and several other books on the lives and careers of fine artists.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue