Fine Art Today recently caught up with the painter for an in-depth inquiry into the man, the artist, and his paintings. His responses were attentive, complete, and sure to intrigue our readers.

Fine Art Today: Share with us a little about your creative process, what inspires you, and how a subject is chosen. Is there a moment as you’re hiking or out in nature when a painting’s subject presents itself to you?

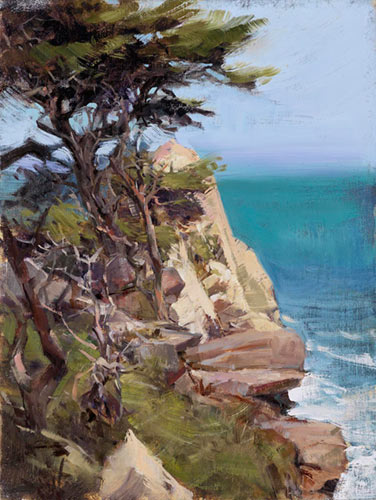

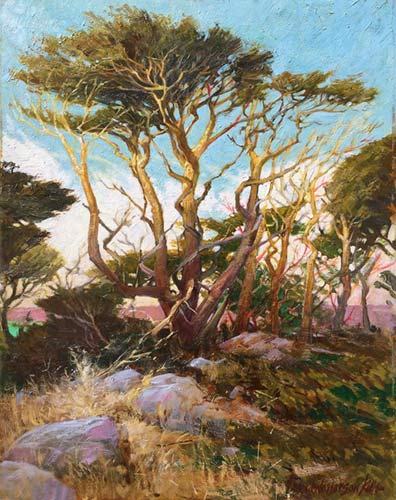

Thomas Kitts: For the most part I paint directly from life, so what I usually respond to first is not so much the scene or subject itself but the quality of the light that illuminates it. Thus, the same subject will feel alive or dead to me depending upon the time of day, or year, or existing environmental conditions. Over the years, I have become interested in natural light because color is light, and the interaction of color is what ultimately becomes my subject. In truth, I am as happy painting the harbor in Vernazza, Italy, as I am painting a free-range herd of pigs rooting through a pile of garbage in a Third World country. The essential thing is that the light is interesting, and most of the time the best light occurs on the margins of the day. In addition, I find the ephemerality of natural light endlessly fascinating, so I will often choose a scene or subject knowing there is little time to capture it. I don’t know why I do this to myself except that I want to keep challenging myself with new ways of working and with new ideas; and all of that comes from the world, not me.

Fine Art Today recently came across a telling quote from art critic and historian Jean Stern discussing Kitts’s use of light. Stern does a superb job of encapsulating how Kitts employs and manipulates light, so we felt it deserved quotation in full:

“No matter what the location of the landscape is, or the climate under which it is painted, Kitts’s work captures the true, natural feel of the light that encompasses that landscape. As it has been with the plein air painters of the past, Kitts has had to endure numerous challenges and difficulties in his determination to get the true effect of fluid, natural light in his paintings. The result is for us the viewer to enjoy, and that is simply the monumental beauty of his work.”

FAT: How do you react or respond to these moments of inspiration?

TK: Honestly, most of the time somewhat frantically. When I see or stumble across a moment that resonates with me, I rush in and immediately begin to paint, often with little planning or forethought. Some deliberation and calculation would be helpful, of course, but I view both to be a luxury when I am working at the speed of life. My best paintings result from being reactive or, as I also describe it, when I enter a flow and just start pushing the paint around. However, having said that, if I do run into trouble, I drop out of the flow and try to resolve the issue before returning to the flow. Or that painting dies right then and there and I move on.

FAT: What is your primary goal in art-making?

TK: Any goals are hard to explain, but I will try. You will rarely find an explicit message or narrative in my work. I am more interested in discovering and exploring the unexpected and even prosaic moments when the world reveals itself. This can be a risky way to find a subject because you must walk around until you see something engaging — which can be utterly uplifting when you find something, or a complete waste of time when you don’t. Yet, as a technician and craftsman (and I try to be both), there are goals and challenges I set and pursue with every painting, and I hope like hell I can meet or surpass them. So if anyone evaluates my oeuvre by subject matter alone, they can become distracted because the thread that ties it all together isn’t so obvious.

FAT: What artists, historical or contemporary, have influenced your work the most and why? Is it purely aesthetic, or conceptual? Both?

TK: I’ve had the good fortune of being inoculated with an extensive dose of art history as an undergraduate, both with classical and modern content, and I remain interested in learning about more artists and movements as I go. I once had a friend who was a painter, a published art historian, and the chair of an influential MFA painting program tell me, “I know a lot about art, but I don’t know what I like,” and I’ve always taken that comment to heart. So knowledge is good, and I have developed a wide range of tastes. My problem has become more about staying focused on the artists who can help me directly. I can be moved to tears by a Bouguereau or Motherwell, excited by the bravura brushwork in a Sargent or Kline, or become analytical upon seeing a Velásquez or Holbein. But no artist or single group of painters excites me more than the Russian Itinerants: Levitan, Repin, and Shishkin, to mention a few.

Ultimately, I look for the things that bind an artist’s work together. I then look for things that bind a group of artists together in a movement or school. Then, I focus on the universals, as they may appear, as much as possible. Because when a formally trained painter paints, he is having a conversation with the artists who preceded him, and hopefully, the artists who will come after.

There are contemporary painters I admire, but I try not to spend too much time looking at their work. Not because I think any less of them, but because I want to retain the clarity of my own voice and the direction I have chosen. Every day I discover yet another amazing contemporary painter, and there are times when there seems to be an infinite supply. So now I feel it is best to hunker down and produce my own work and follow my own path in my own way.

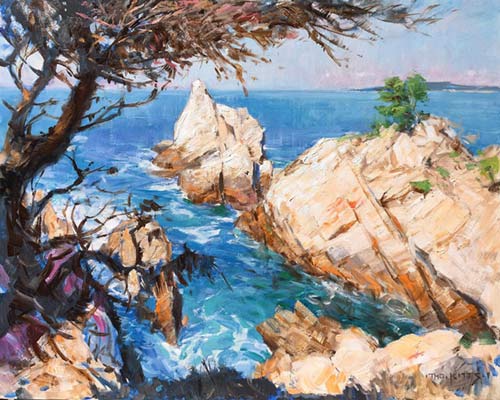

FAT: Your surfaces are entrancing, with undulating troughs and ridges that communicate such energy. How important is the surface/mark-making to you and what do you try to communicate with your work that is independent of composition, value, color, etc.?

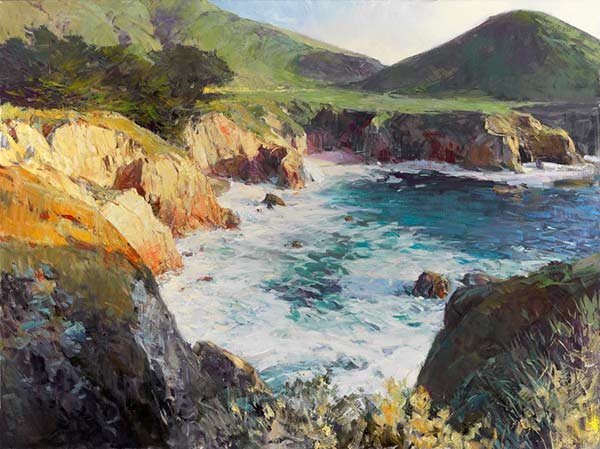

TK: Thank you. You have hit on two points that have become increasingly important to me as I mature. Paint handling is unpredictable, and I think of how I push it around the same way a jazz player thinks about improvising a solo. You have to train and become skillful yet open to the vagaries of the media, and things rarely happen the same way twice. I want the surface of my work to remain lively, and I want the gestural movement created by the push and pull of the paint to convey an emotional immediacy. However, I am not poking at the canvas willy-nilly. There is thought and intent and conscious control as I try to surprise the viewer. Brushwork can be compared to calligraphy. It is personal and should reveal the hand of the artist. Most paintings by mature artists can be properly attributed by brushwork alone.

Here is a statement prepared by Kitts recently:

“When people view my work I want them to see a painting, not a photograph. I want them to experience a surface rife with color, texture, and movement, but also feel connected to the reality that gave birth to the art. Up close, I want the surface to visually explode. From a distance, I want it to reassemble into a whole and create a plausible sense of space and form. But most of all, I want my audience to appreciate why I try to paint from life as much as possible — and thus share our wonder at the world.”

FAT: You mentioned in your teaching philosophy that one must never underestimate how much you can learn from your students. Can you share with us an important moment when teaching led to a profound learning experience for you?

TK: I had the privilege of teaching painting and drawing and chairing a department at a small private art school from 1990 to 2000; while it didn’t pay much, it was a wonderful life experience. It was a time and place when I could test artistic ideas with hundreds of students and assess the success. In addition, I was able to work with those students over a considerable period of time, over three years, actually, and this encouraged me to look at art with a longer perspective. I felt honored that my students let me help shape their voices and not simply copy or emulate mine.

FAT: Where will Thomas Jefferson Kitts and his art be in 10 years? How do you see your evolution continuing and what do you hope to achieve in the future?

TK: That is difficult to predict with any degree of confidence, but if my present interests and trajectory hold, I expect to keep taking risks with my work. One of the nicest things a fellow professional has ever said about me is that I take risks. Meaning, I will chance making a major change to a painting without knowing if it will lift or crash the work. (How do you know unless you give it a try?) Or I will invest significant time in a subject without knowing if it will appeal to a collector. (Who am I painting for, them or me?) Or simply, I will start something without knowing if it can be completed in the time available. (Others have done it, can I?) I took my friend’s statement to heart because I know it is tempting to develop a routine, method, or shtick that will permit me to crank out manneristic work lacking much meaning or substance.

But to try and answer your question more directly, let me share one final artist quote. This one comes from Hokusai at the age of 95: “If Heaven granted me another five years, I could have become a real artist.”

You never stop. You keep on and let everything else settle behind you in your wake.

Thomas Jefferson Kitts has a new exhibition showing from August 1 through September 30 at James J. Rieser Fine Art in Carmel, California.

To learn more, visit Thomas Kitts.

This article was featured in Fine Art Today, a weekly e-newsletter from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine. To start receiving Fine Art Today for free, click here.