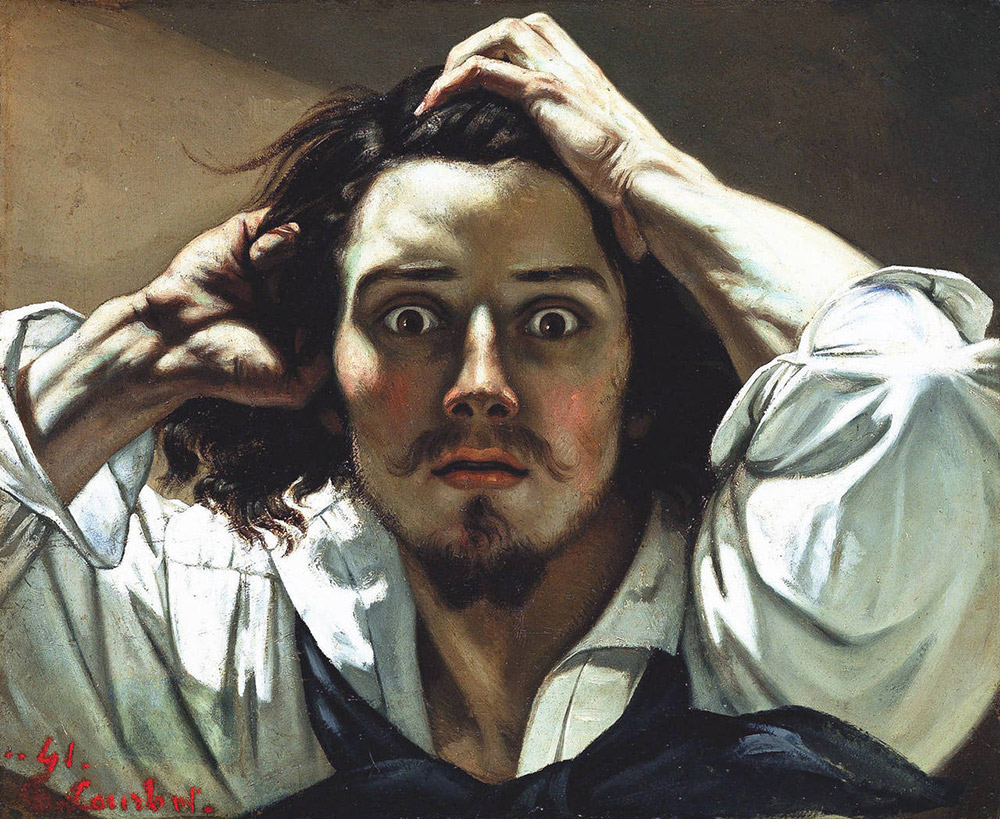

In this highlight, view a historical and contemporary example of superb quality and skill: Gustave Courbet, “The Desperate Man.”

The self-portrait has long been employed by artists to convey different messages or psychological states in their art. In fact, the exploration of the inner being through self-representation has been well documented among some of the most influential and monumental figures in Western and Eastern art.

However, few artists have investigated their own souls to such an extent that their bodies of self-portraits provide an autobiographical description of their journey through life. Immediately, one thinks of Rembrandt, the 17th century Dutch master who left us nearly 90 representations of himself from the time he was an adolescent to months before his death. Similarly, other significant figures such as Max Beckmann, Albrecht Dürer, and Van Gogh have all been recognized for the deep psychological tone of their self- representations.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) can be added to this illustrious group of artists. As one of the most recognized painters of his time, Courbet earned success as a young man, though a period of uncertainty and financial misery pervaded his life until the mid-1850s. Further, letters to family, friends, and patrons suggest that even as late as 1860, Courbet was susceptible to melancholy.

Significantly, between the years 1840 and 1850, Courbet produced nearly 24 self-portraits that offer his viewers a glimpse into the formulation of his early identity and psychological evolution. As scholar Dominique de Font-Reaulx has noted, “the early self-portraits are a window into the artist’s early training and development. The visual habits formed in these works would continue throughout his oeuvre.”

However, Courbet is seldom recognized as being connected to the themes and ideologies of the Romantics, who enjoyed the apex of their success around the time of Courbet’s birth in 1819. Courbet found his career in a transitional period that saw Romanticism coming to a close and subsequently, the birth of realism and modernism in European visual culture. However, his early self-portraits would seem to argue differently, suggesting Courbet was acutely aware of and inspired by traditions extending back to Dürer in the 16th century and Rembrandt in the 17th.

Courbet’s “Self-Portrait as the Desperate Man” is one early example, produced in 1845, at the apex of the artist’s melancholy and Romantic disillusionment. Courbet presents himself frontally in a tight, claustrophobic, horizontal frame. His expression seems to be one of both fear and psychosis. His arms are raised to his head, clenching his dark hair, with tensed muscles bulging from his wrists and forearms. There is no escape, and the confrontation with the viewer achieves an intensity rarely witnessed in the history of art.

It has been suggested that Courbet’s goal was to “share the intensity of a moment in which the artist, having come to the end of his Romantic education and suddenly overcome at the spectacle of his imminent downfall, finds the strength to repudiate a destiny that is not his.” In this way, it proves to be a key work in the artist’s life, and it remained in his studio until his death.

This was Courbet’s chance to express what he had not done in his letters and his desire (to use his words), “to bury the amorous follies of my youth.” This is precisely why self-portraiture was so attractive to Romantic artists, and it touches the core nature of self-portraiture as a genre. Indeed, in this way, Courbet’s “Desperate Man” is quintessential Romanticism in every sense of the term.

Pushing it further, Courbet could have appropriated Renaissance imagery, which would add yet another Romantic tone. Consider Albrecht Dürer’s etching “The Desperate Man” of 1514 — the central figure bears a strikingly similar gesture and mood. Note the clenched fists that grasp the figure’s hair and the raised arms, which seem too similar to Courbet’s rendering to be mere coincidence.

To learn more, visit the Musee d’Orsay.

(This article was originally published in 2017)

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue

[…] Vinci | William Bouguereau | VG Gallery | Italian Renaissance | Study | Museo del Prado | BC Edu | Fine Art Connoisseur | Artble | Caravaggio | […]

[…] attached article from the Fine Art Conniseur” (https://fineartconnoisseur.com/2017/06/portrait-of-the-week-gustave-courbet-the-desperate-man/) mentions suggestion that Courbet’s goal for this […]

[…] https://fineartconnoisseur.com/2017/06/portrait-of-the-week-gustave-courbet-the-desperate-man/ […]

[…] Gustave Courbert’s , Desperate Man (1844-5) and Lucian Freud Self-portrait from 1963), both oils, they gaze down with hands in or […]

[…] his paintings to portray fear, thought, despair, etc. Gustave Courbert hands touch his head in Desperate Man (1844-5). Hands gestures can be very expressive, but just the presence of the hand near the face […]

[…] https://fineartconnoisseur.com/2017/06/portrait-of-the-week-gustave-courbet-the-desperate-man/ […]