Through June 24, 2018

J. Paul Getty Museum

From The Getty Museum:

One of the most intriguing series in Rembrandt’s oeuvre comprises his drawings made in the style of artists serving the Mughal court in India. Juxtaposing Rembrandt’s depictions of Mughal rulers and courtiers with Indian paintings and drawings of similar compositions, this exhibition reveals how contact with Mughal art inspired Rembrandt to draw in an entirely different, refined style prompted by his curiosity for a foreign culture.

Among the most surprising aspects of Rembrandt’s prodigious output are 23 surviving drawings closely based on portraits made by artists working in Mughal India. These drawings mark a striking diversion for this quintessentially Dutch “Golden Age” artist, the only time he made a careful and extensive study of art from a dramatically different culture. Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India explores for the first time the artist’s Mughal drawings, exhibiting them alongside the Mughal paintings that inspired them to assess the impact of Indian art and culture on Rembrandt’s artistic interests and working process as a draftsman.

“Rembrandt may be one of the most famous painters in European art history, but there are still remarkable discoveries to be made about his work,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “This exhibition is a case in point, demonstrating how Rembrandt turned to the art of India to produce some of his most intriguing images. This vivid example of cultural exchange reminds us how artists on different continents take inspiration from one another, a reality that of course continues to this very day.”

The exhibition pairs 20 of Rembrandt’s surviving drawings depicting Mughal emperors, princes, and courtiers with Indian paintings and drawings of similar compositions, which had been brought to Amsterdam from the Dutch trading post in Surat. Rembrandt’s portraits reveal how his contact with Mughal art inspired him to draw in a newly refined and precise style.

Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India also examines how global trade and cultural exchange impacted artists working for Mughal emperors in India, who were in turn inspired by Dutch and Flemish printed images of European rulers and scenes of daily life. Among the treasures found in a Dutch East India ship, which sank en route to China, was a package that contained four hundred prints by and after Dutch and Flemish artists. This astounding quantity suggests that Dutch merchants thought that art would help them gain access to the Asian market in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

These prints were particularly interesting to Mughal court artists, who were already accustomed to working with single-tone drawings and calligraphy. Rather than copy the European compositions exactly, Mughal artists adapted them to their own artistic purposes, as seen in Keshav Das’s “Roman Hero” (about 1590-95), based on prints by the Dutch artist Hendrick Goltzius. The use of these prints illuminates the range of images that found a positive reception in India long before Rembrandt made his creative copies.

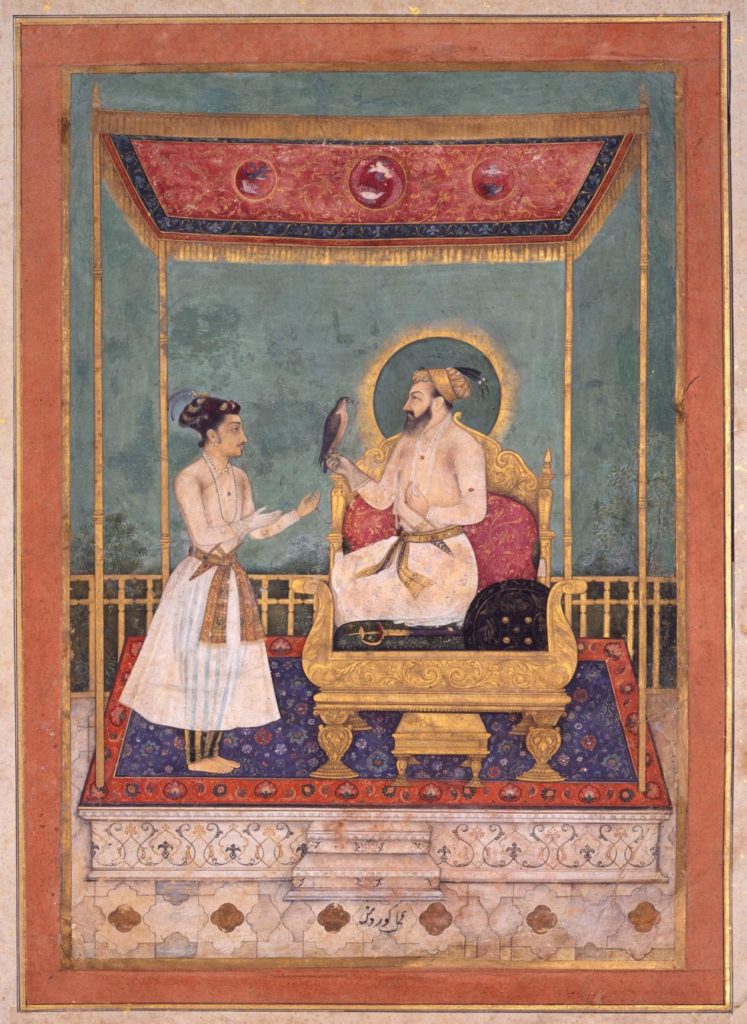

The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1627-1658) was well known for his patronage of the arts — most notably the building of the Taj Mahal. Shah Jahan’s rule of Mughal India spanned the years that Rembrandt worked in Leiden and Amsterdam. In his eight drawings of Shah Jahan — more than he made of any other Mughal ruler — Rembrandt carefully studied the trappings of imperial magnificence, as seen in “On Horseback (Shah Jahan)” (about 1656-61). The poetic claim that Shah Jahan was “Royal Rider of the Piebald Steed of the World” was not lost on Rembrandt.

Rembrandt’s drawings after Mughal compositions constitute the largest group, by far, of his copies after other works of art. Moreover, they are his only surviving drawings on expensive Asian paper, which suggests the high value the artist himself placed on them. “Shikoh” (about 1656-60) is quite different from the typically known “late Rembrandt” style of drawing. His careful attention to details of clothing, jewelry, turbans, and footwear pays tribute to Mughal artists’ exceptional artifice.

On almost every level, Rembrandt and the Indian court painters operated in completely different worlds. Yet such differences did not prevent these innovative artists from appropriating foreign imagery to reflect upon and enrich their own more familiar artistic practice and culture.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

Nice museum