“Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857–1907” is a new book by Eve M. Kahn, published by Wesleyan University Press (available here). Enjoy this excerpt and learn more about Mary Rogers Williams, “the Mary Cassatt you’ve never heard of.”

Excerpt from “Forever Seeing New Beauties: Why She Matters”

Mary Rogers Williams (1857–1907) is the only nineteenth-century woman artist for whom it is possible to relate in detail where she traveled, from the Arctic Circle to Roman ruins south of Naples, along with her evocative comments on what she ate, what political scandal was splashed across the newspapers, which street urchins tugged at her heart, what plants were clinging to nearby rock formations, what smells were wafting through the streets, how much she paid for tram rides, which hotel guests fascinated or bored her, what she thought of better-known painters and men’s treatment of women on the road, which museum shows and church restorations she loved and hated, what she was wearing, and how much she missed home—while she was sketching fjords, medieval doorways, harbors, chateau spires, and parched hillsides.

She is also surely the only nineteenth-century woman artist who fell into deep obscurity, while thousands of pages of her letters and mounds of other family paperwork plus virtually all her paintings were slumbering together in storage. The quantity of documentation, even about the ordinary, is part of what makes her story extraordinary.

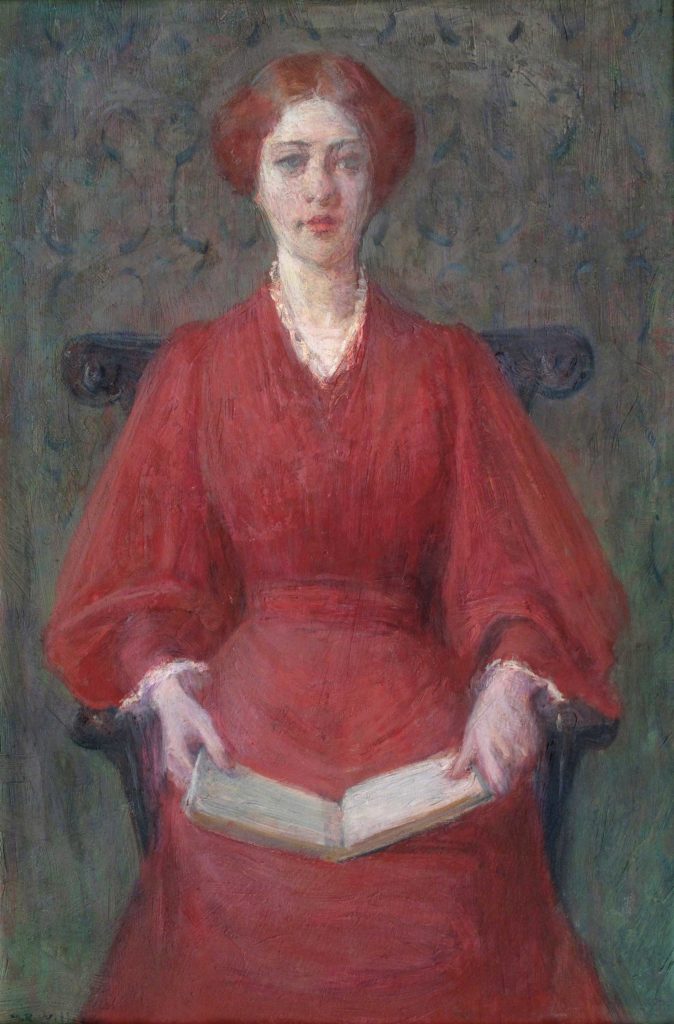

Mary has been called “the Mary Cassatt you’ve never heard of.” The two Marys, both Impressionists, did share a love for painting women and for bohemian living in Paris. But while Mary Cassatt enjoyed inherited money and patrons’ support and socialized with Degas’s circle, Mary Williams was a baker’s daughter who had little uninterrupted time for art. Mary Williams taught at Smith College for nearly twenty years to help pay her family’s bills.

But please do not feel sorry for her, or think of her as a martyr. Mary, above all, had fun, within the limitations of her budget and her era’s misogyny.

Her writings record not only her travels but also the travails of teaching female pupils and competing with men for space on gallery walls. Her story affords a rare woman’s perspective on nineteenth-century cosmopolitan life: Why were women not allowed to linger on ocean liner decks at night? Why did Italian waiters urge her to get married already? Why did Dwight Tryon, her Smith department head, believe that women could be taught so little about art? Why did he get the credit for what students achieved, although he spent only a few mornings each semester on campus?

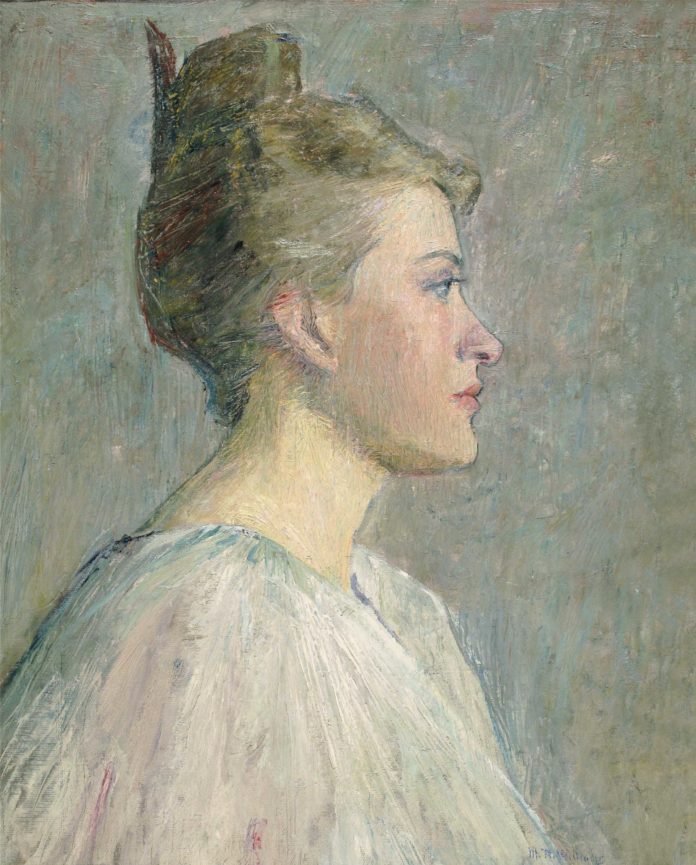

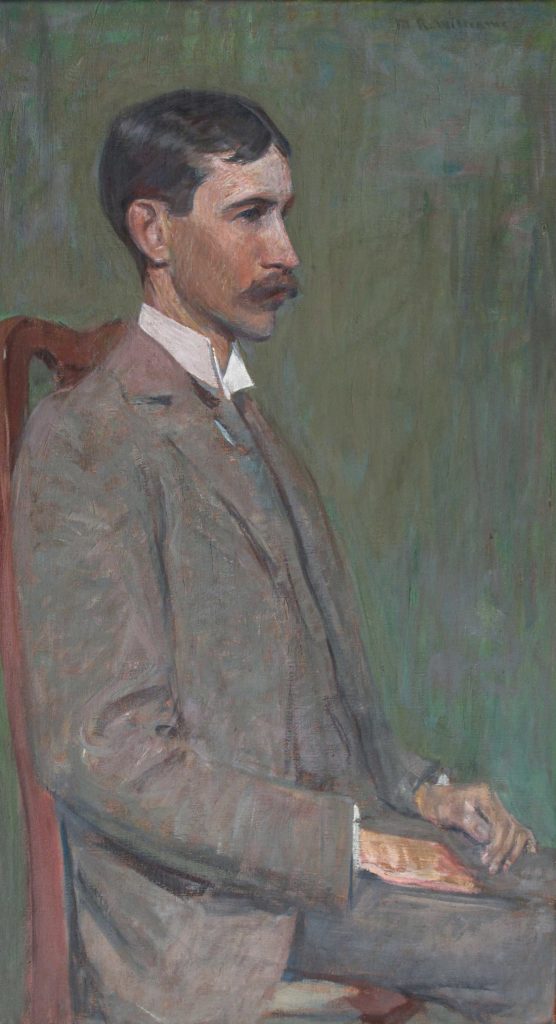

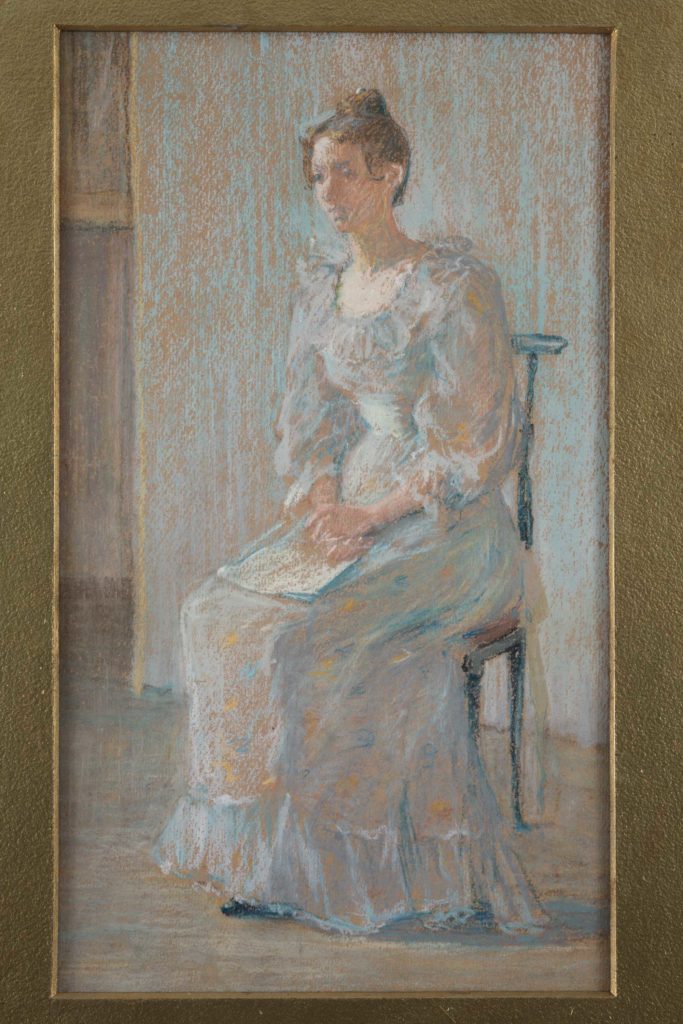

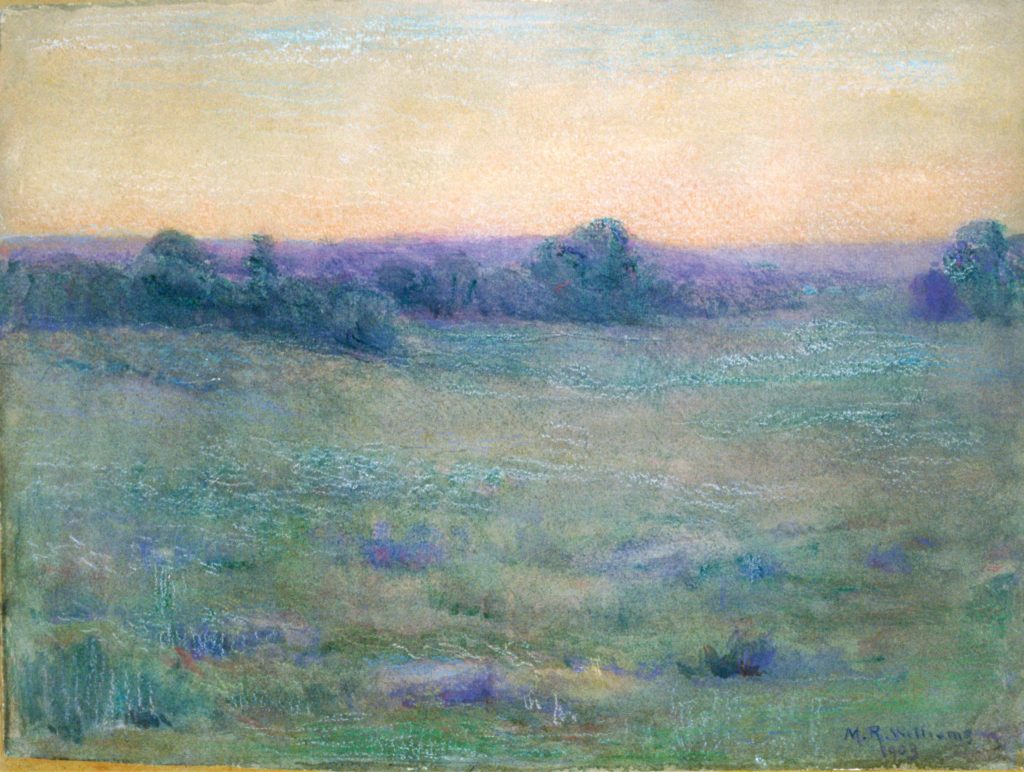

About 100 of Mary’s oil paintings, pastels, and watercolors and 160 sketches survive, many of them long kept in the Whites’ boathouse. She exhibited in Paris, New York, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Hartford, Boston, and Springfield and Northampton, Massachusetts, and she was lauded in publications including the New York Times. Henry White compared her to “those New England women of artistic temperament of whom Emily Dickinson, the poet, was an example.” But while Emily Dickinson scribbled in her upstairs bedroom, for Mary there was almost no such thing as too much time on the road. In her travels, Mary would try almost anything, including escargots, subways, wood carving, bookbinding, and sneaking out at night to see comets.

At Smith, along with teaching art and the history of art and sculpture, Mary hung exhibitions of student pieces and borrowed artworks, organized faculty parties, tried to flatter donors, handled her own housework and cooking, painted landscapes as well as portraits of Smith students and staff, and submitted and shipped her paintings and pastels for American exhibitions. She published a few writings about art, and she occasionally sold a work. On vacations with her family, she took charge of feeding everyone, and while living in Europe, she cooked, stoked heating stoves, painted and papered walls, waxed her floors daily, and made and repaired her own clothes. A single male artist of her time, even under similar financial constraints, would not have been expected to handle many of the chores that fell to her.

She knew celebrated artists, including James McNeill Whistler, Albert Pinkham Ryder, William Merritt Chase, and Childe Hassam. She liked Ryder, despite his absentmindedness and chaotic home, and she did not mind Chase, who had critiqued her early on for “too much timidity!” But she found Hassam’s work repetitive, and as for Whistler, she concluded after a few classes at his Paris school that he was a pompous fop surrounded by fawners. She dropped out of the school—and in general, she was anything but a joiner.

In artistic style, she has been classified recently as a Tonalist and an Impressionist. From the 1880s to the 1910s, Tonalist painters used a limited and largely somber palette to evoke the moods of landscapes rather than fine details. The Impressionists, who emerged in the 1860s in France, likewise set out to break away from realism, but they favored brighter hues and broader subject matter—from factories to brothels— than did the Tonalists. Neither category, as we now conceive them, existed in Mary’s lifetime. And while she knew Tonalists and Impressionists who congregated at Florence Griswold’s boardinghouse in Old Lyme, she scarcely socialized with them. She lived in Paris for years (1898–1899 and 1906–1907), but she befriended no Parisian art world celebrities—she does not seem to have met, for instance, Mary Cassatt.

Mary simply described herself as “forever seeing new beauties.” She did not analyze her brushstrokes, which at times gave only suggestions of buildings, foliage, land contours, and faces. In 1894, in her only published interview, “when asked what style she proposed to adopt, she replied: ‘If I cannot have a style of my own, I trust I may be spared an adopted one.’”

Little trace of her remains in the archives of more famous people; if anything had been filed there, historians might have rediscovered her before I stumbled upon her in 2012. She died unexpectedly; she had no time to organize her papers and place artworks in private and institutional collections. Henry and her unworldly sisters tried futilely to perpetuate her legacy.

Imagine what she could have accomplished if she had been longer lived, or rich, or a married man—if she had been allowed to concentrate year-round in her own studio, with servants or a spouse or lover or dutiful child to help, if anyone had promoted her in her lifetime or concentrated after her death on sharing her work widely with dealers, scholars, and collectors.

Mary, however, would likely scoff at any suggestion that she would have been better off privileged. She disliked wealthy people. Her letters are full of anecdotes about boring namedroppers, Americans who learned nothing while traveling and mangled foreign languages, and artists who repeated themselves or copied Old Masters. And she doubted her own talents for painting, teaching, and writing. “I know I was not built for an imparter of information,” she told Henry. In 1908, the Springfield Republican eulogized her: “She had an almost pathetic tendency to think less of her work than it deserved.”

One professional feat she apparently never attempted or even wanted to, unlike so many of her colleagues, particularly men, was painting a self-portrait.

When Mary was told that people loved her letters, and were delightedly passing them around, she was surprised that she had not bored anyone, or so she said. She must have suspected that her words sent across the Atlantic were powerful, as she sat in the glow of oil lamps or candlelight scribbling descriptions of radishes and cauliflowers striped and stacked on a French produce truck, mauve clouds during an Arctic Circle eclipse, and tasseled uniforms on British palace guards. Mailing the letters home to her sisters from Europe, she told them, gave her “one moment when I feel sure that I’ve done just the right thing.”

About the Author

EVE M. KAHN is an independent scholar specializing in art and architectural history, design, and preservation, and was weekly Antiques columnist at the New York Times, 2008–2016. She contributes regularly to the Times, The Magazine Antiques, Apollo, and Atlas Obscura.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

Thank you so much for article on Rogers… the other Mary Cassatt. I would add that Berthe Morisot was also be one. She was friends with Cassatt and they supported each other in a man’s world.

[…] Fine Art Connoisseur – Mary Roger Williams […]

I am reading The Art Spirit and Robert Henri writes about her. I am glad to find your article to learn more about an admirable woman in the arts.