From Fine Art Connoisseur’s “Today’s Masters” series on contemporary master artists, a spotlight on Eileen Hogan >>>

Master Artists > Eileen Hogan: Painter-Craftsman

BY PEYTON SKIPWITH

Eileen Hogan (b. 1946), the subject of a 2019 retrospective at the Yale Center for British Art, is one of the most admired figurative artists working in Britain. Though not a familiar name in the often sensation-seeking world of contemporary art, she is no recluse, instead serving as professor of fine art at University of the Arts London, trustee of the Royal Drawing School, and former dean of Camberwell College of Art, where she founded the Camberwell Press.

Over the years Hogan has completed major projects for the Imperial War Museum, the All England Lawn Tennis & Croquet Club at Wimbledon, H.R.H. Prince Charles, and London’s Garden Museum, where she served as artist-in-residence in 2017. These activities and many others are recorded in the well-illustrated, multi-author catalogue Eileen Hogan: Personal Geographies (Yale University Press) that accompanied the exhibition. On view were 70 paintings, 20 sketchbooks, and a dozen books, most never exhibited in North America before.

Now in her early 70s and at the height of her powers, Hogan is truly a painter-craftsman.

Born in London of Irish stock, she has been a compulsive observer, draftsman, reader, recorder, and note-taker since childhood; these habits were honed from age 9, when she was confined to a hospital bed with rheumatic fever for an entire year. At 14 Hogan was already attending Saturday-morning classes at Camberwell School of Art and Design, and she became a full-time painting student there two years later.

Her four years of study were followed by three more at the Royal Academy Schools in London, then a year’s scholarship to the British School at Athens and a further three years at the Royal College of Art. This trajectory constituted a thorough grounding by any standard, but also allowed Hogan a slow and steady development.

At Camberwell, Hogan was obliged to take a subsidiary subject and opted for lettering, submitting herself to the rigors of cutting individual letters in lino from which to print texts. Words have always attracted her, both for their letter-forms and their quirks of usage: they appear frequently not only in her heavily annotated sketchbooks, but also as the motifs that have kick-started various series of paintings.

Examples include the names of such fishing boats as Bountiful, Sweet Promise, and Golden Gain (along with their ports of registration), the names of the beehives in the artist-poet Ian Hamilton Finlay’s renowned garden at Little Sparta in Scotland, or even his battered watering can, Kettle Drum.

A city-based landscape painter may seem to be something of a contradiction, but like the London Impressionist before her, Paul Maitland (1863–1909), that is exactly what Hogan is. Sky, for example, is of little interest to her and is almost invariably omitted from her landscapes.

In his introduction to the catalogue of Maitland’s memorial exhibition in London, Walter Sickert described him as living in “Kensington Gardens by day and on the Chelsea Embankment by night.” This is a pattern that Hogan instinctively appreciates; with its rich grays and rusty-clover tints of old iron, her “Trinity Buoy Wharf 1” echoes Maitland’s Thames-side evocations.

Here we see a grim industrial site with its clutter of rusting metals; on a gray day they possess a certain melancholy beauty, bearing witness to the fact that no aspect of the London landscape is too humble to escape Hogan’s scrutiny.

She finds equal delight in the quotidian and the grand, having painted settings as mundane as a community garden, a deserted football ground, and rubbish skips that residents have converted into planters, and as prestigious as the bluebell woods at Kew Botanical Garden and the patrician squares of London’s West End. In all of these instances, Hogan has gravitated toward enclosures rather than rolling countryside.

In 1998 Hogan painted a series of works based on four squares in London — Bryanston, Manchester, Montague, and Portman — through which she walked most mornings on her commute from home to studio. These, and others such as Edwardes Square, which she has also painted, are both public and private: everyone can walk by and admire them through the railings, but only owners of the surrounding houses hold keys to access the enclosed gardens.

In Hogan’s depictions these squares are usually bereft of people, though she notes “there may be an echo or a trace of someone — a bench just vacated, a man in a hat disappearing at the edge.” These squares represent for her the contrast between the human and inhuman aspects of London — a city that is at once a hive and a place of loneliness, a dichotomy that never ceases to intrigue her. In fact, Hogan is also a considerable painter of portraiture, a discipline she says she became involved in “by stealth.”

PEOPLE

Early in Hogan’s career, she saw trees as more important — more individual — than people. For her, a tree has always been specific, not generic, particularly the great London plane trees with their irregular, knobbly trunks and scaly bark, which she loves to draw and paint. People, on the other hand, tended to be little more than cyphers, useful for rhythm or color notes as needed.

By the early 1990s, however, this began to change. While painting a picture inspired by a luncheon in the gardens of the Chelsea Arts Club, her Royal College tutor, Carel Weight, began to emerge as an identifiable figure. Though not depicted in detail, he is clearly recognizable to all who knew him by his stance.

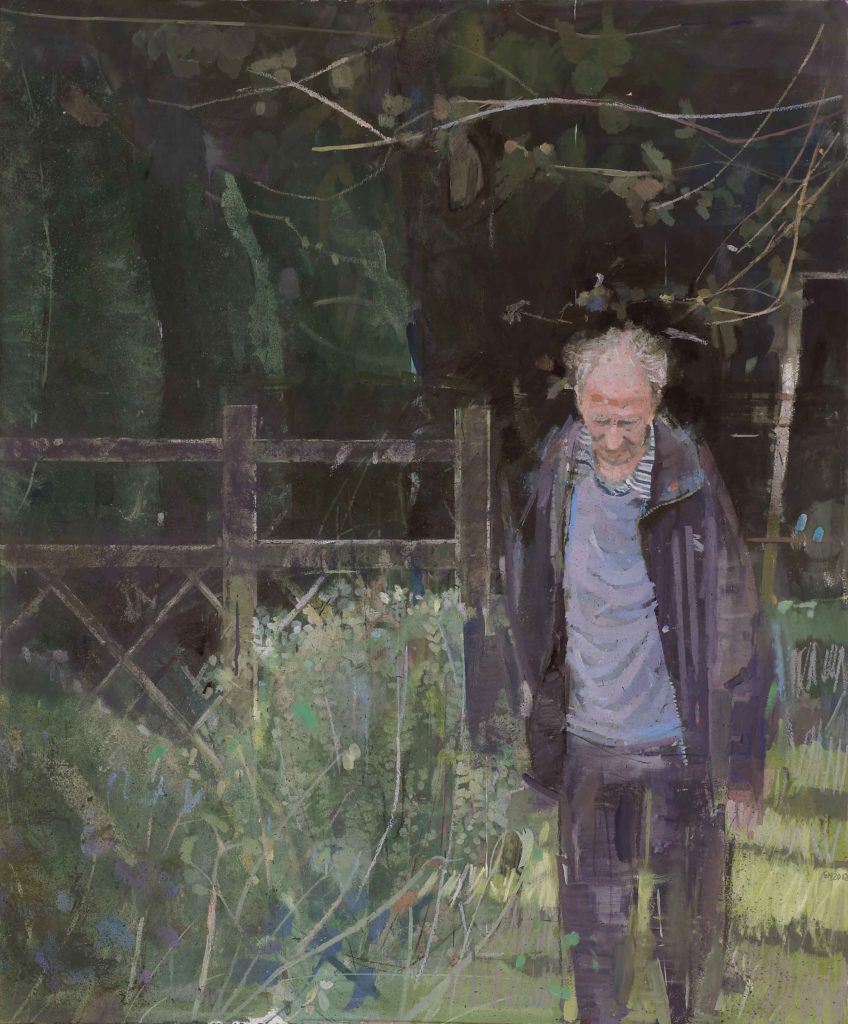

Since then, Hogan has continued to capture the body language of her subjects, as we can see in the series of paintings of Ian Hamilton Finlay, one of which is now in the Yale Center for British Art’s permanent collection. Hogan had originally encountered Finlay when her partner, Cathy Courtney, was interviewing him for the British Library’s oral history initiative.

Since then, Hogan has sat in on the interviews of many other individuals, noting how their expressions and postures change as they describe different experiences and phases of their lives. Her portrait study of Brian Webb wearing the robes of Master of the Art Workers’ Guild caught the attention of the Prince of Wales, leading him in 2015 to commission portraits of “Tony” Leake and Alistair Urquhart as part of a series he conceived to honor the surviving veterans of D-Day 70 years on. Later Prince Charles commissioned portraits of himself and the Duchess of Cornwall, as well as a record of the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle last July.

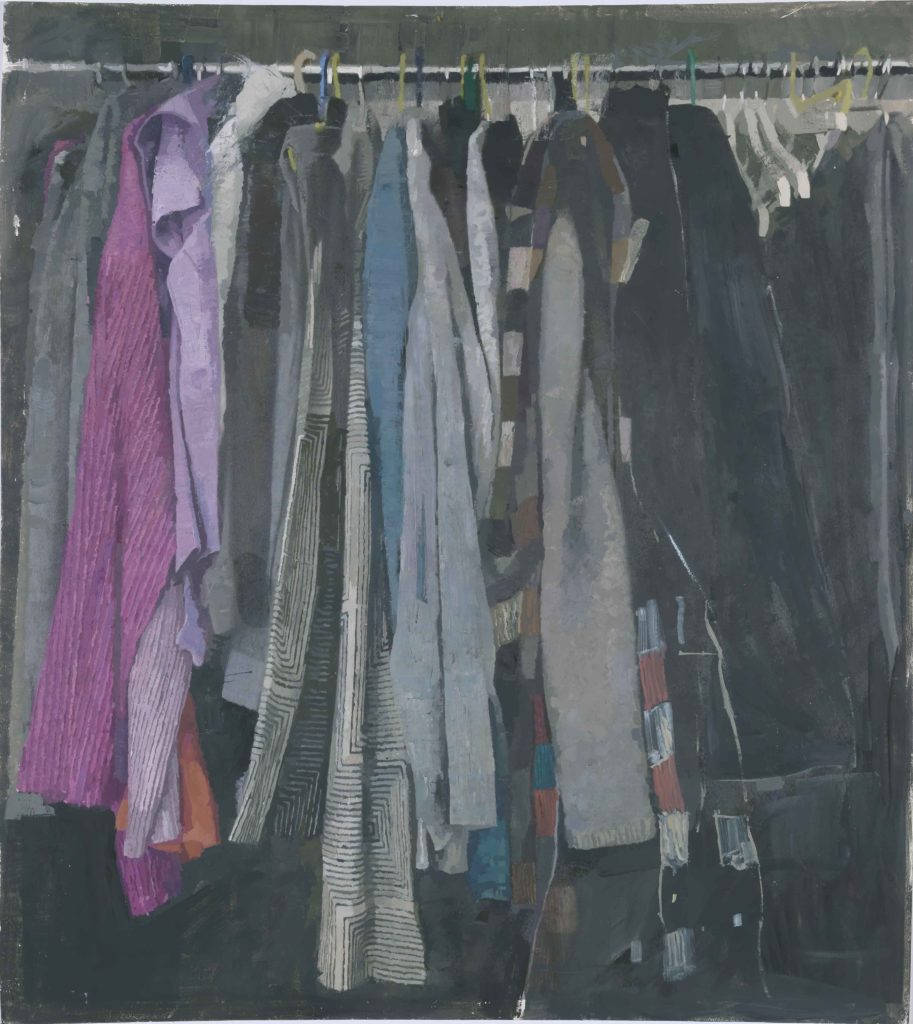

For any artist, the most readily available model is oneself. Hogan’s large “Self-Portrait in Pembroke Studios” — in her typical hues of gray, gray-green, and mauve, with strong emphasis on the geometrical pat-tern of furniture, the paint trolley, and bare floorboards — is one of her most ambitious to date. She has also painted Self-Portrait through Wardrobe 2; though she does not actually appear here, her presence, individuality, sense of style, pattern, and design clearly identify her as the absent sitter.

STARING FOR LONG STRETCHES

Pattern and design have always interested Hogan, coming to the fore during her year in Greece, where the strong, clear sunshine dramatized contrasts between light and shade. This particularly impressed her as she sat in sidewalk cafes observing the world, leading to a series of paintings and watercolors based on chairs and shadows.

The ornithologist W.H. Hudson, while recalling his boyhood on Argentina’s pampas in Far Away and Long Ago, describes his ability to stand motionless “staring at vacancy,” a propensity that disturbed his mother until she discovered he was observing birds and insects. Hogan shares this ability, and indeed the poet W.H. Davies’s lines — What is life if full of care / We have no time to stand and stare? — could almost have been written for her.

Some years ago, Hogan sent me a postcard from Tuscany illustrating a detail of a painting by Piero della Francesca — one of her favorite artists. On its back she wrote, “The churches and museums have been almost empty so lots of room to draw and stare for long stretches. It’s perfect.”

Hogan is contemplative by nature. She works slowly and thoughtfully, and her paintings evolve by degrees. She draws and redraws her subject, starting from notes and sketchbook jottings, which may be no more than a few seemingly random lines, then gradually working up her composition. Hogan often uses photographs as an aid, computer-manipulating them to help isolate and define the underlying geometry of her composition.

Initially she works on a small scale to produce a near-definitive study, often no bigger than a postcard. If this pleases her, Hogan will paint a larger version, laying her paper flat and covering the surface with a layer of wax before starting to define the composition with small marks, made with sable brushes to create a delicate tracery. Then, after adding another layer of wax, she mounts the paper onto thick card so she can place it on her easel and start working more freely with larger brushes and with charcoal.

In this painstaking manner, Hogan’s grand compositions finally emerge. Few are grander and more reflective of this technique than “Chelsea Physic Garden 2, 8 September 2016,” in which every touch of the brush is as light and sparkling as the airborne water droplets emitted by the sprinkler itself.

In 1956 the suspense filmmaker Henri-Georges Clouzot directed his only documentary, The Picasso Mystery. In it, the maestro created an entire painting on camera, but then Clouzot reversed the footage to show the brushstrokes being “removed” one by one. For a moment, the painting improved before the whole thing fell to pieces.

I have known Eileen Hogan for almost 40 years and have watched her develop as an artist; she has seldom, if ever, spoiled a work by going too far. Just the opposite, in fact, as she has never been beguiled by the heavily laden brush and bold gestures. Even early in her career, though confident, she would stop short rather than outrun her ability to control the final image. Those works from the 1980s retain a tentative yet delightful quality.

I recall one instance when Hogan borrowed back an older painting of seagulls from this period for an exhibition; having grown in experience, she recognized its shortcomings and proceeded to take it a stage further, ignoring the fact that it was no longer her property. Fortunately, the owner, a practitioner of the law, agreed that she had considerably improved it, but still felt bound to issue a written reprimand, which Hogan remembers to this day.

It is incredible to think that, at some future date, Hogan might look back on “Self-Portrait in Pembroke Studios” or “Chelsea Physic Garden 2” and wish to improve them, yet, despite her 73 years, she feels she is still learning. It is rare, and a true distinction, for an artist’s later works to be her best, but Hogan seems destined to join that elite circle.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter to discover more spotlights on master artists