An excerpt from a Fine Art Connoisseur feature on the Western Art of Thomas Blackshear (who is on the faculty of the upcoming 2nd Annual Realism Live virtual art conference), written by Michael J. Pearce

Western Art, Western Nouveau

The golden glow of success has gathered around Thomas Blackshear II (b. 1955). In September 2020 his painting “Swan Song” (above) was a smashing success at the 14th annual Jackson Hole Art Auction, where it sold for $77,350 — more than double its high estimate. That same week, Blackshear’s painting “Hunter’s Watch” appeared on the commemorative poster of the Jackson Hall Fall Arts Festival and then sold for $37,000.

The following month, he was inducted into the Society of Illustrators’ Hall of Fame, an honor previously accorded to such legends as Maxfield Parrish, Norman Rockwell, and Dean Cornwell. This past March, three new Blackshear paintings — “The Wait,” “American Nobility,” and “Native American with Feather” — appeared in the Masters of the American West sale at Los Angeles’s Autry Museum of the American West, where “The Wait” won the Artists’ Choice award.

It is easy to see why. Blackshear’s “Western Nouveau” paintings are light, decorative, and elegant, a romantic and fresh kind of imagery that has captured the imagination of Western art connoisseurs, who always have a sharp eye for a rising star.

Divine Inspiration

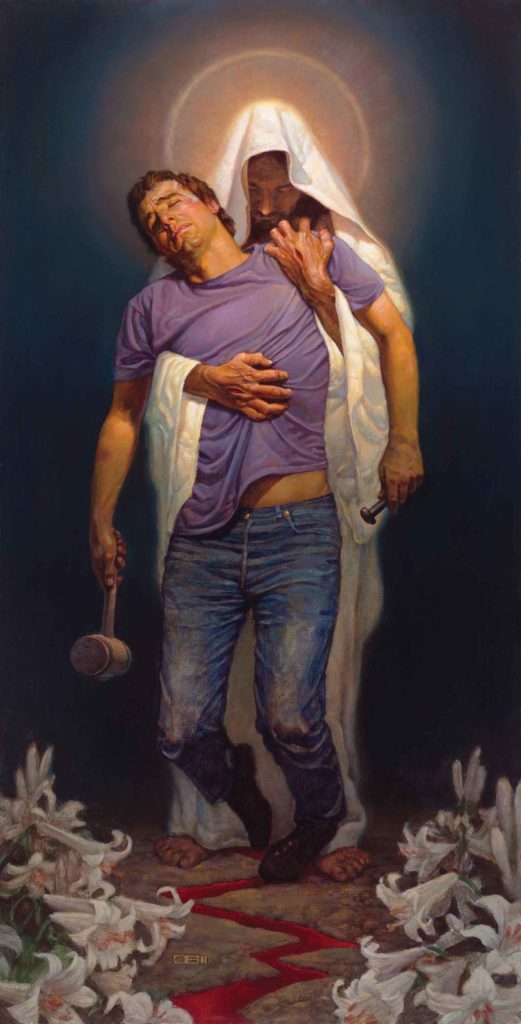

Blackshear has found divine support. He has a deep Christian faith, and has long enjoyed success selling religious paintings and prints to evangelical churches throughout the U.S. Prayer and painting are closely tied, which makes this body of work a spiritual journey for Blackshear.

Gold is the most material of substances, but it also symbolizes God. So, does the gold he paints with have a spiritual component? Blackshear is ambivalent about whether the gilding itself might be spiritual, in the way that monks illuminating their manuscripts once considered their craftsmanship as prayer.

His religious imagery transcends denominations. When a friend set off on a missionary trip to India, Blackshear gave him a selection of his own prints. In Calcutta that friend visited Mother Teresa (1910–1997) and offered her two of them — “Forgiven” and “Coat of Many Colors, Lord of All.”

She asked him, “May I put them in the room of the dying?” Of course, the friend agreed, assuming she would hang them in a hospice ward. A year later, the friend met a nun from Mother Teresa’s facility who invited him to visit the hospice. Not seeing the Blackshear prints anywhere, he asked what had become of them. His guide replied, “You misunderstood. When Mother Teresa asked, ‘Do you mind if I put it in the room of the dying?’ she meant herself.” In her last days, St. Teresa had kept Blackshear’s prints in her bedroom, which is now a shrine to her memory. In 2010, he was commissioned to design a U.S. Postal Service stamp commemorating her.

A lay spirituality is manifest in Blackshear’s paintings of Native Americans, who are elemental guides. Here he follows the conventions of Western art, painting indigenous people as “noble savages” and flavoring their images with romanticism. The men bear smoking incense that curls around them in decorative flourishes that are also seen in Mucha’s gorgeous embellished posters. Blackshear’s “Native American Nouveau” features a warrior wearing a headdress fashioned as a butterfly’s wing, suggesting the transience and fragility of the tribes.

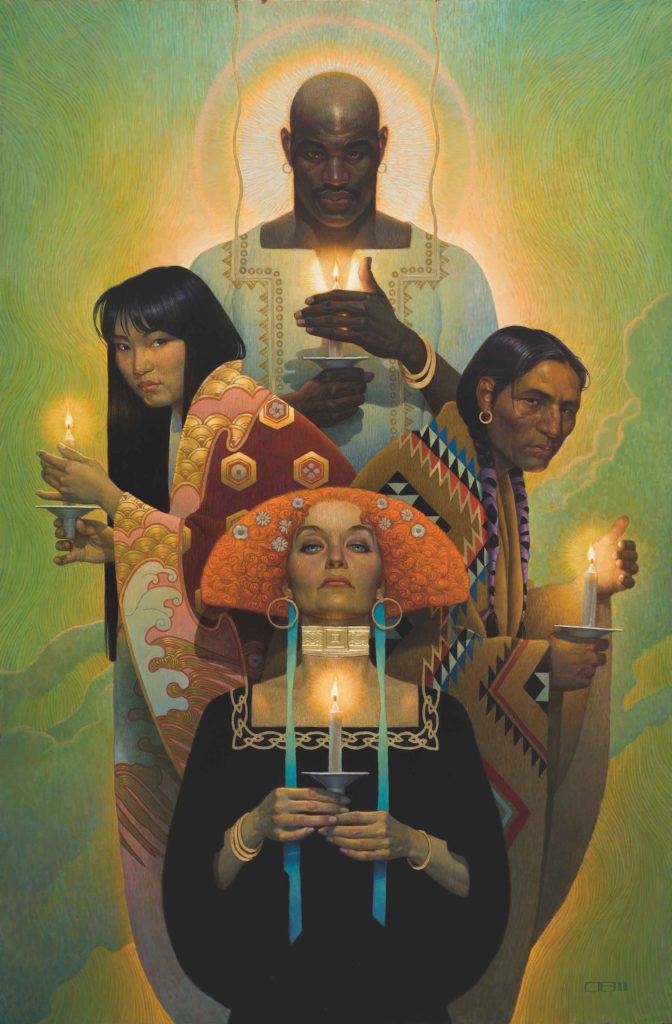

Blackshear’s “A Common Thread” echoes the heartfelt plea for racial tolerance that Rockwell conveyed in his famous “Golden Rule (Do unto Others)” in 1961. Figures representing the four races bear lit candles; they are unified as a community, as light-bearers, as keepers of the flame of decency and truth, which they hold up against the threatening darkness of intolerance.

Though decorative, Blackshear’s Western paintings avoid much of the sentimental excess that afflicts the genre. His images of black cowboys are a necessary reminder that the Old West wasn’t actually as white as Hollywood has suggested. Wrapped in rawhide, his rugged black buckaroos chew tobacco and smoke with the same machismo as their white colleagues.

“The Wait,” Blackshear’s latest addition to a series examining African-Americans’ role in shaping the U.S., is a powerful reminder that black Union soldiers also paid the ultimate price in the Civil War: 180,000 black men served in that fight for justice, and thousands died in battle or hospital.

Blackshear’s soldier waits for a better world. Moving forward in time, “Airman’s Inspiration” is a sensitive portrait of a Tuskegee pilot with the wings of Perseus, caught in a quiet, beautiful moment with a hummingbird balanced on the finger of his leather gauntlet. Yes, there is nostalgia and romance in Blackshear’s work, but it is aimed at a broad and inclusive audience, an audience of all Americans.

Visit Thomas Blackshear’s website at thomasblackshearart.com, and learn from him in person at the 2nd Annual Realism Live virtual art conference.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue