BY MATTHIAS ANDERSON

The artist Jon deMartin (b. 1955) has spent much time in Venice drawing, painting, and studying the methods of the many historical Venetian masters who have long inspired him.

Over the years, his annual visits have prompted a subtle “sea change” in his artistry, a move from a naturalistic approach to one that is — in his words — “more felt,” more reliant on his own drawings and his own memory. This evolution has been somewhat surprising even to deMartin, who is hardly a newcomer to art. A native of Wilmington, Delaware, he graduated from Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute with a B.F.A. in filmmaking, then studied fine art in Manhattan at the Art Students League, School of Visual Arts, and New York Academy of Art, as well as privately with Michael Aviano.

Throughout his Venetian initiative, deMartin has “sought to work out a reliable method that supports what I want to express, because how I approach the painting, on the technical side, profoundly influences the outcome. This has been a fascinating, difficult, and passionate adventure, during which I have developed a certain degree of confidence in my process so I that can focus on the idea.”

Ever the educator, deMartin has lectured about this aesthetic journey at such institutions as Studio Incamminati (Philadelphia) and Grand Central Atelier (New York City). His talks are peppered with relevant quotations by the greats of art history, from Leonardo to Hopper, and illustrated by examples of his own work at every stage of the process.

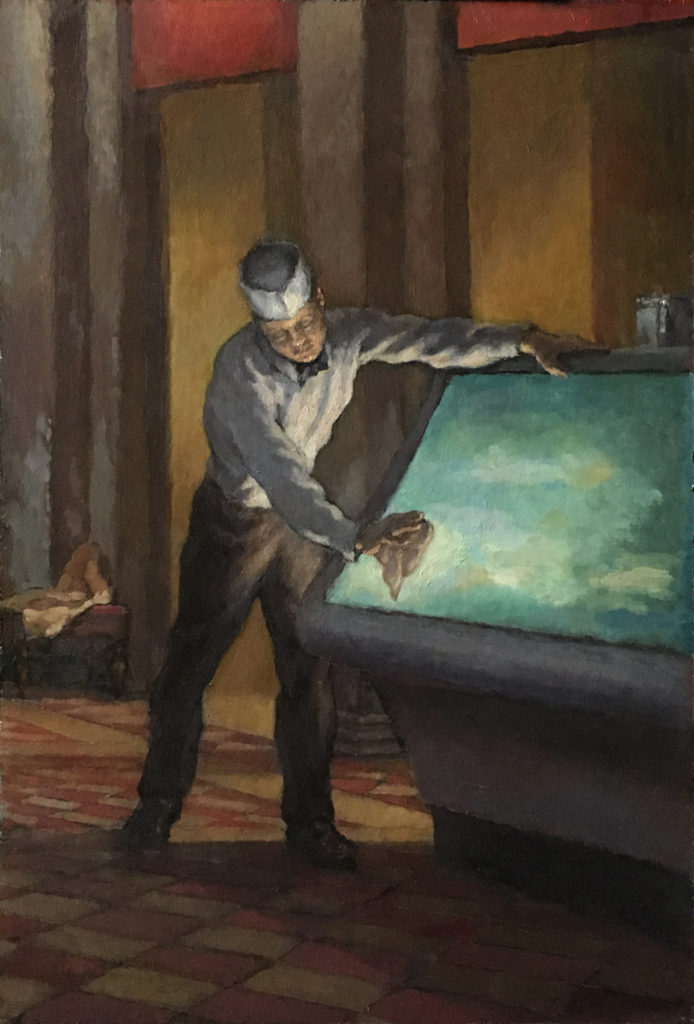

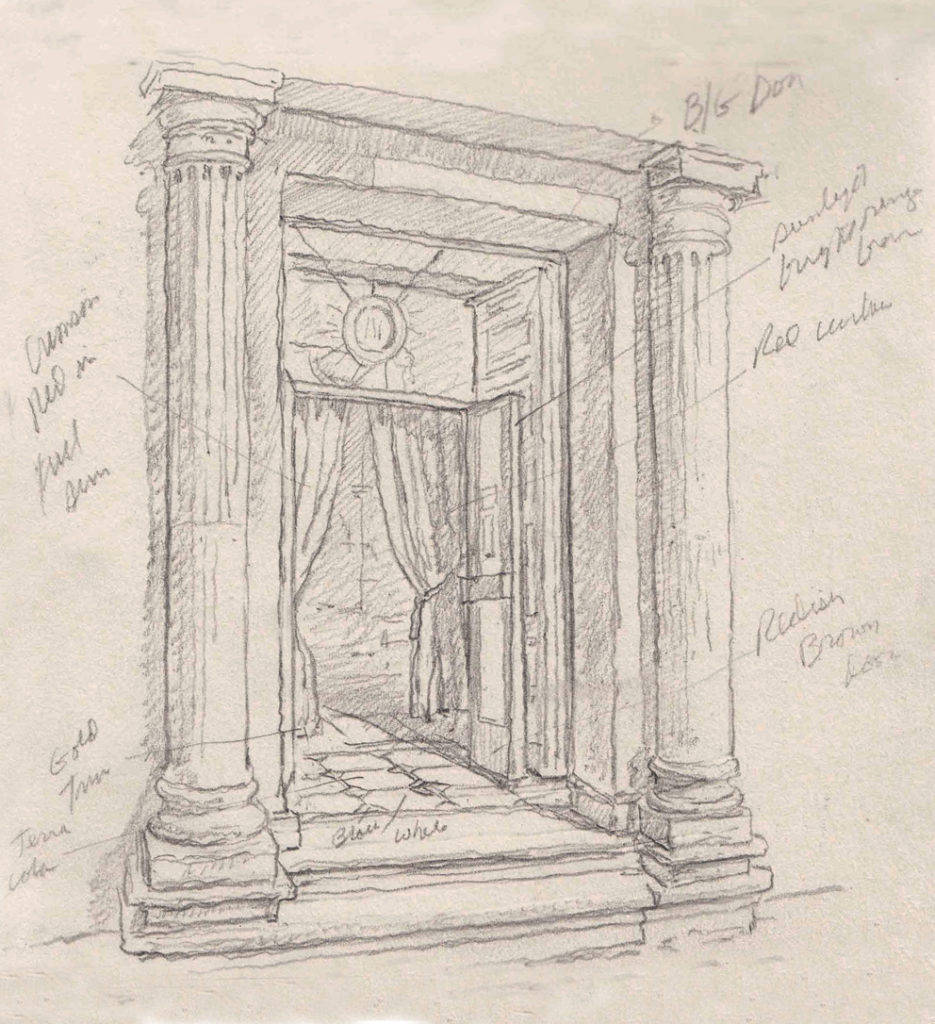

Illustrated here are a few of his paintings of Venetian subjects, and also an architectural study he drew there. Note the recurrence of smart phones in these scenes: deMartin is not seeking to turn back time, but rather to show the city and its people as they are today.

SELECTING THE ESSENTIALS

At the heart of deMartin’s self-discovery is his decision to no longer paint from life, but instead from drawings he has made from life, and also from his own memory. He stresses that the act of drawing forces the artist to “select the essentials,” eliminating the clutter of what does not matter. On occasion, he concedes, his photographs of a model or setting become useful in double checking backgrounds or colors, but never can a photograph select the essentials as a drawing does.

Logically, deMartin begins with the idea, allowing nothing to impede his imagination — especially reality. He always has paper and pen handy in case inspiration strikes unexpectedly, and he sees his compositional drawing as the initial “gesture” of the painting that will ultimately emerge. During its preparation, important questions may arise, such as, “Is this painting going to be about the figures or the setting?”

Having drawn a composition, no matter how tentatively, deMartin begins to draw figure poses from his imagination. Like past masters, he also feels free to borrow poses from historical sources, which is why having a good art library is helpful. He urges his students to conceive and draw the main figure, the background figures, the props, and the setting before they hire a single model or go outdoors: “I have wasted precious modeling time and money by not being prepared,” deMartin admits.

Once the models arrive, the artist makes drawings that purify their forms down to the essentials, always depicting them nude before drawing them clothed. DeMartin also draws the entire pose even if part of the body will be cropped out later. He notes that experienced models can provide unanticipated insights, but, like actors in rehearsal, they need a clear-headed director who already has a compositional drawing (or script) well underway. Having continuously sought to strengthen the image’s overall graphic power, deMartin “squares up” the final compositional drawing in order to transfer it to the canvas that he will paint.

After finalizing his color palette so that he can concentrate on the act of painting, deMartin begins to integrate his drawings of the models or architecture. Knowing that he may have to adjust the composition as the painting process unfolds, his goal now is to create “expressive, three-dimensional lines with spontaneous and flowing figures.” This approach means deMartin has abandoned the use of cartoon transfers (which, he says, “force me to color between the lines”) and of oil sketches (“which use up all of my expressive energy before I even get to the final canvas”).

Reasonable as this approach may seem to laymen, it is still not fully understood in the world of American classical ateliers. Fortunately, this is a free country, without a nationalized system of art instruction, so deMartin can do as he wishes, and we all can enjoy the results illustrated here. We at Fine Art Connoisseur look forward to seeing what comes next from his lively brushes and pens.

Connect with Jon deMartin at jondemartin.com.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue