Spotlight on the John F. Peto Studio Museum > Experts have come to acknowledge this artist as one of the leaders of late 19th-century America’s trompe l’oeil movement.

By Allison Malafronte

John F. Peto’s legacy has been enhanced by the preservation efforts of a team formed by Peter and Cynthia Kellogg, who used to own his Island Heights home. In 2010, after a five-year, $2 million renovation, this group opened the home to the public as the John F. Peto Studio Museum. And in September 2020, the Kelloggs donated the building to the museum’s board, which is now growing the permanent collection while planning exhibitions, events, and projects that highlight Peto’s significance.

Although his trompe l’oeil (“trick the eye”) still life paintings are owned by major museums nationwide, and although famous talents like Jasper Johns and Roy Lichtenstein have paid homage to him in their own work, John F Peto (1854–1907) has remained relatively obscure in accounts of American art history. Perhaps that’s due, at least in part, to the fact that he avoided both the spotlight and chasing commercial trends, preferring instead the family time, artistic reflection, and spiritual replenishment he enjoyed at his year-round cottage home in Island Heights, New Jersey.

Another factor contributing to Peto’s posthumous obscurity was the wrongful attribution of many of his paintings to William M. Harnett (1848–1892), whom Peto befriended while they were studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Peto admired Harnett’s style and emulated it for a short time, which accounts for some of the confusion. But from 1949 onward, thanks to careful research by the art critic Alfred V. Frankenstein (1906–1981) and the perseverance of Peto’s only child, Helen, Peto’s name was eventually reassigned to dozens of his paintings. Since then, experts have come to acknowledge him as one of the leaders of late 19th-century America’s trompe l’oeil movement.

Beginnings

John Frederick Peto was born in Philadelphia, the first of five children in a tight-knit family with whom he always remained close. By the age of 22, he had a studio on Chestnut Street near various friends and family members involved in the arts. Peto was also a musician and played the cornet in the Philadelphia Fire Department Band and at church meetings. At 23 he enrolled at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, just a year after Thomas Eakins was (controversially) forced to leave his post as director. Though Peto stayed only a year, he continued submitting his paintings to the academy’s high-profile annual exhibitions.

In 1889, when he was 35, Peto and his new wife, Christine, moved to Island Heights, a summer resort town on the Jersey coast he had gotten to know while visiting two aunts there regularly. Records reveal that Peto originally moved to “The Heights” in order to open a photography studio — following in the highly regarded footsteps of an uncle — before turning his full attention to painting. He designed and built a house at the corner of Cedar and Westray Avenues, then constructed a studio addition a few years later. This is where Peto spent most of the rest of his life, painting and taking photographs surrounded by the artworks and objects that inspired him, as well as his beloved wife, daughter, and two aunts.

While Peto basked in his sanctuary, friends and colleagues such as Harnett — who often tried, and failed, to persuade Peto to travel with him — were enjoying commercial success in Philadelphia, New York City, and other major markets. Peto earned a modest income by selling his paintings to tourists or bartering them with local businesses, sometimes supplementing it by playing his cornet for the Island Heights Methodist Camp Meeting or taking in summer boarders. After his premature death from a kidney condition at 53, Christine remained in their home, taking in boarders. Later Helen — followed by her daughter Joy Peto Smiley — ran the house as a bed and breakfast. Ultimately, three generations of Petos lived there for more than a century until Joy’s passing in 2002.

Stepping Back in Time

Today, when visitors arrive at Peto’s two-and-a-half-story Victorian house — located just north of the Toms River where it flows into Barnegat Bay — its rusty red and ochre façade offers few hints of the rich artistic heritage inside. During its extensive renovation (2005–10), every effort was made to return both the exterior and interior to their appearance in 1907, the year Peto died. Using family photographs, archeology, and materials analysis techniques such as paint microscopy, the team replaced older shingles with cedar shakes, demolished several add-ons, restored the original rooflines and shutters, and reconstructed the front porch.

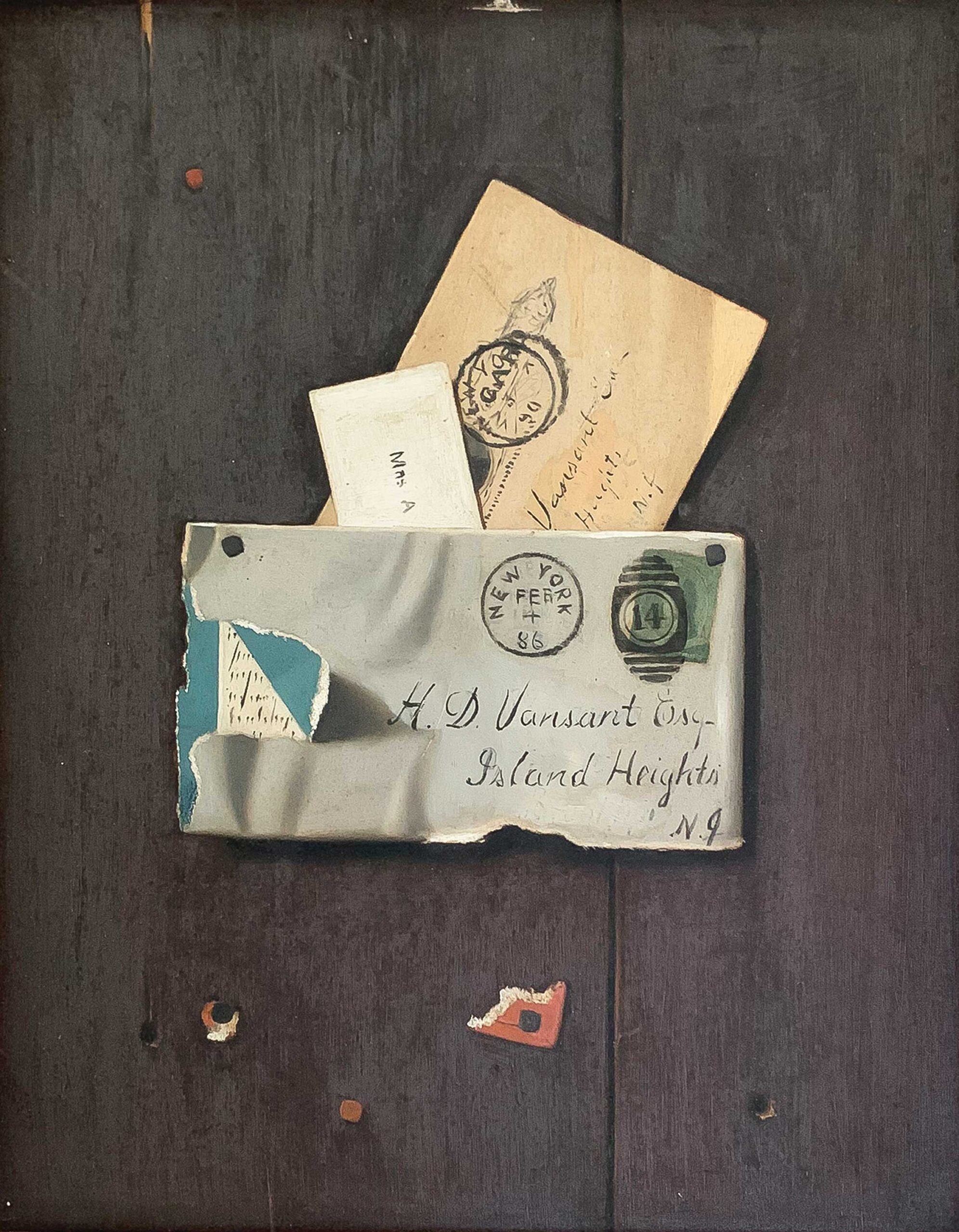

Walking through the front door is like stepping back in time. Throughout the 12 rooms on public view are pieces of period furniture, many original to this house; some of the actual books, candlesticks, vases, and ephemera that appear in various Peto paintings; his palette, brushes, and jars of medium; and examples from his collection of artworks and artifacts. Even the bright aqua wall color Peto selected has been replicated by analyzing a paint sample retrieved from the ceiling and then searching through more than 60 paint mixtures to find an exact match.

Then there’s the art itself, displayed throughout the first floor, which encompasses the studio, parlor, office, and kitchen. The museum’s growing collection contains 22 original Peto paintings obtained through purchase, loan, or gift. Among them are seven recent acquisitions from a board member and from a local whose ancestors knew Peto. Various stages of the artist’s career are represented, with most emphasis on his trompe l’oeils and less on the landscapes. Rounding out the collection are several paintings by his Philadelphia-based contemporaries — such as Franklin D. Briscoe, Fred Wagner, and Emily Perkins — as well as black-and-white family photographs.

Because no photographs of the five upstairs bedrooms survive, the restoration team felt free to convert them into gallery space, where visitors now enjoy rotating exhibitions throughout the year. When asked how he selects these projects’ themes and participating artists, the museum’s “Arts & Artifacts Curator,” Harry Bower, explains that he is not limited strictly to trompe l’oeil or New Jersey. “We show both regionally and nationally known artists working in genres that complement Peto’s lifelong interests, subject matter, and style,” he says. “Recent exhibitions have included Thomas Eakins in New Jersey, The Women of Peto, and Trompe l’oeil Meets Photo Realism.”

A retired art educator as well as a fiber artist, Bower has lived in Island Heights for more than 40 years and knew Joy Peto Smiley when she ran the bed and breakfast during the 1970s. He became further interested in 1983 while exploring the National Gallery of Art’s ground-breaking exhibition Important Information Inside: The Art of John F. Peto and the Idea of Still-Life Painting in Nineteenth-Century America.

After Joy’s passing in 2002, Bower was invited to join the house’s steering committee. Two decades later he remains enthralled with Peto’s art. “He was inspired by the everyday,” Bower notes. “When you look around his home and at the paintings themselves, you see many common objects: a good book, a good pipe, and a good beer quite often show up. Sometimes I look at the bold, bright colors in his paintings and think, ‘Was he influenced by those colors because he surrounded himself with them in his home, or was it the other way around?’”

Where An Artist Creates Reveals Why

Perhaps it was both. Peto may have been drawn to commonplace objects, but his penchant for vibrant, uncommon colors is evident in both the objects he chose to depict and in the palette in which he decorated his home. “Walking through its rooms offers an opportunity to experience the inspiration that Peto found every day in the profusion of lush yellows, blues, reds, and greens,” writes Valerie A. Balint in her Guide to Historic Artists’ Homes & Studios (2020). She continues, “His paintings on display reveal that the same colors often appear in his work. The combination of original furnishings, objects, and artwork against this vibrant backdrop offers unique insight into Peto’s creative process and means of expression.”

Much of Peto’s later work was marked by expressive color, along with his usual attention to light, texture, and precise technique. It also became increasingly introspective and somber: ruminations on objects with history, meaning, and a story to tell, be they weathered books, newspaper clippings, rusty violins, or official documents that once belonged to his father. (A picture-frame gilder and dealer of fire-department supplies, Peto’s father was an enduring influence throughout the artist’s life.)

Viewing artists’ work in the context of where they created it is always enlightening. The John F. Peto Studio Museum is one of 48 sites currently in the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s network of Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS), and it’s well worth the journey to coastal New Jersey — or any other location cited in Balint’s useful HAHS guide — to experience them in person.

“Art is the result of both a physical and mental practice, but what is displayed in a museum represents only the results,” Balint observes. “Artists’ homes and studios help us imagine the form of this rigorous process by allowing us to see where art was actually made…. [T]hey reveal not only an artist’s process, but what in the environment inspired it. The working spaces, the objects the artists chose to surround themselves with, the books they read, and the views they regarded beyond their studio walls all inform what they created.”

Plan your visit to the John F. Peto Studio Museum at petomuseum.org.

View more art museum spotlights and announcements here at FineArtConnoisseur.com.