Death. It can be a frightening concept for some, a liberating one for others. The Egyptians were consumed by it, and most of their art and architecture that survives was in service of death. A fascinating new exhibition in Maine that delves into mortality — and morality — in Renaissance Europe may shake you to your core.

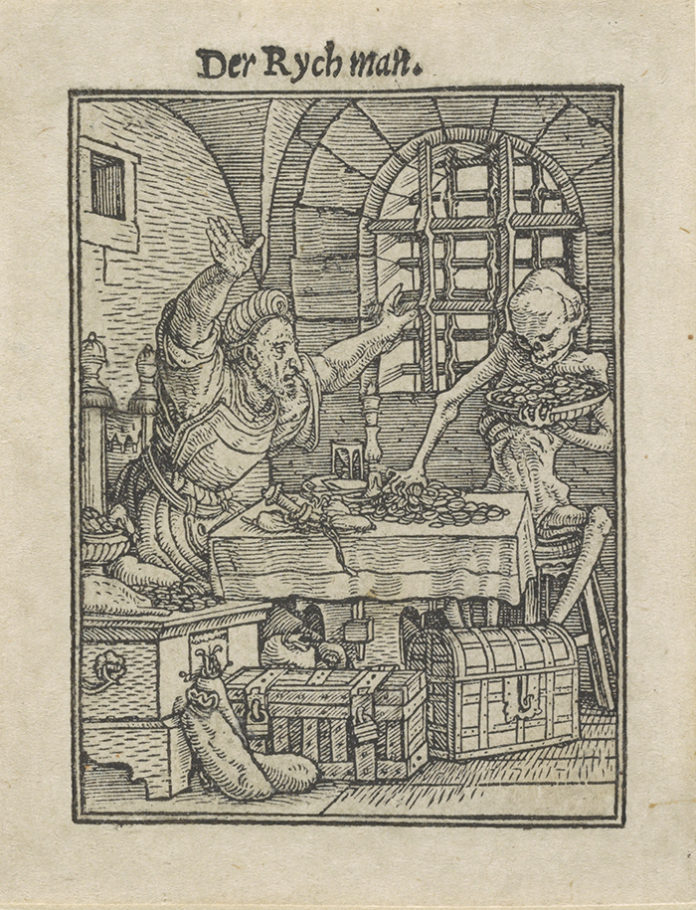

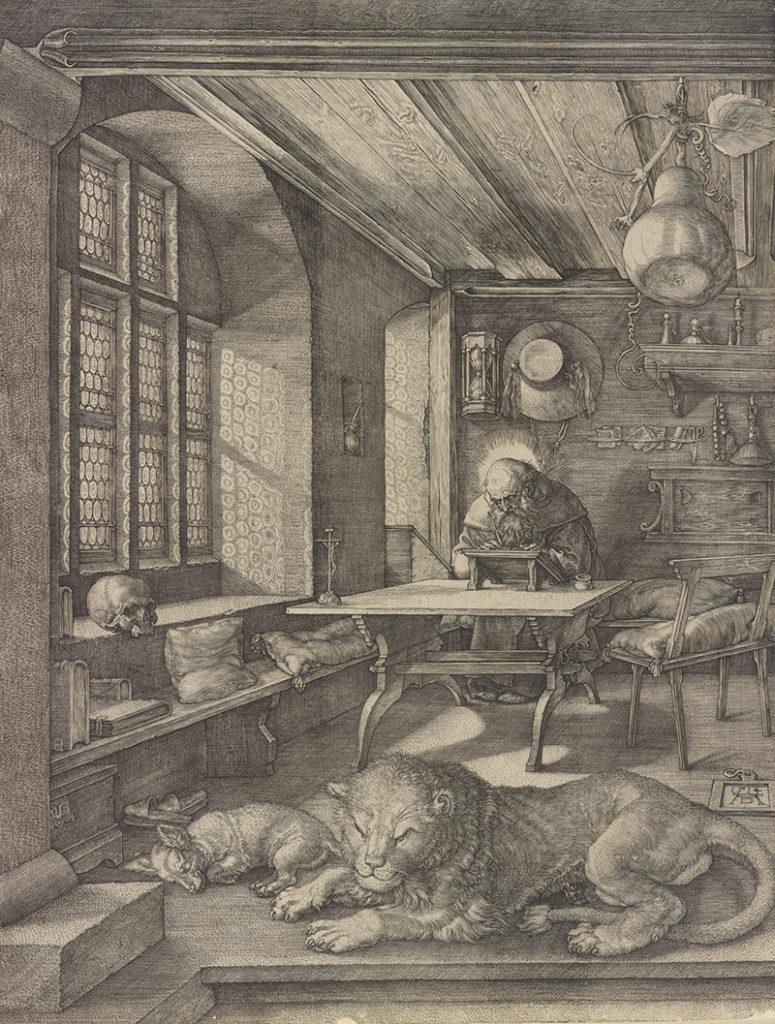

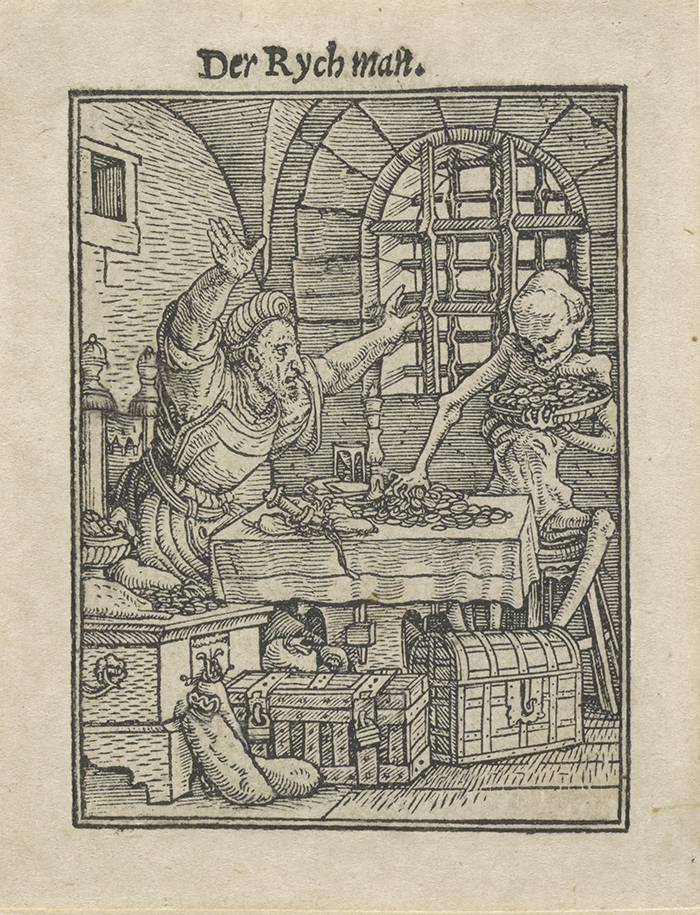

The Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, Maine, recently unveiled a chilling but beautiful exhibition of nearly 70 objects from major North American and European museums titled “The Ivory Mirror: The Art of Mortality in Renaissance Europe.” Curated by the college’s Peter M. Small Associate Professor of Art History, Stephen Perkinson, the show reveals how “in an increasingly complex and uncertain world, Renaissance artists sought to address the critical human concern of acknowledging death while striving to create a personal legacy that might outlast it,” the museum writes. “[The exhibition] brings together exceptional examples of ‘memento mori,’ a genre of artistic and literary imagery that emerged in the early Renaissance to remind viewers of their inevitable death, to question how art historians have conventionally interpreted these objects and to propose new ways of considering their significance.

“‘The Ivory Mirror’ will bring together nearly seventy exquisite artworks, many of which have never been seen before in North America, from European and American institutions — among them the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Huntington Library in San Marino. New scholarship across the humanities features critical new discoveries, such as the attribution of several ivories, of previously uncertain authorship, to Chicart Bailly, a prosperous ivory carver active in Paris from at least the 1490s until 1533. The precious objects included in the exhibition — from ivory prayer beads and gem-encrusted jewelry to exquisitely carved small table sculptures — draw attention in spectacular fashion to the depictions of death, dying, and decay that proliferated in popular culture between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, when mortality rates were perilously high. The appeal of objects featuring macabre imagery urging us to ‘remember death’ — and, by implication, to consider how best to take advantage of our time on earth — reached the apex of its popularity around 1500, when artists treated the theme in innovative and compelling ways.”

The show, which opened on June 24, will continue through November 26. To learn more, visit here.

This article was featured in Fine Art Today, a weekly e-newsletter from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine. To start receiving Fine Art Today for free, click here.