We are all in this together. Everyone who reads Fine Art Connoisseur believes not only in representational art, but also in the talent, training, rigor, and dedication required to attain excellence in this field. Though the artists appearing in this issue are generally faring better than their counterparts did, say, 40 years ago, it’s still not easy for them to get noticed or make a living, so I’m always keeping an eye open for kindred spirits in other cultural sectors from whom we might borrow ideas.

Recently I learned about the Michelangelo Foundation for Creativity and Craftsmanship, established in 2016 to preserve master craftsmanship by celebrating artisans’ capacity to make something of lasting beauty with their hands. The foundation supports people who make — for example — lace, leatherwork, haute couture, crystal, musical instruments, and porcelain, though there are many more products involved. Based in Geneva and initially focused on Europe, the foundation was created by Johann Rupert, the founder of Richemont, the Swiss-based group that owns such luxury brands as Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Montblanc, Alfred Dunhill, and Chloé. His co-founder is Franco Cologni, who had previously established the Cologni Foundation for Artistic Craft Professions, which is focused only on Italy.

At first it seems ironic that the executives who cultivated a global demand for European luxury goods are now worried about sustaining the artisans who make those very goods. Accidentally, you see, they have created a monster, as Rupert once explained to The New York Times: “What’s not fun anymore is going to Bond Street or Fifth Avenue or Via Montenapoleone where the shops and product all look the same, and have done for the last 30 years, because all the smaller, independent artisans have been pushed out by the retail rentals.”

Exactly. One obvious symptom of globalism is homogeneity. It is much easier to manufacture and distribute worldwide just a few kinds of Cartier watches, to name one example of a luxury good. Cartier is a revered brand and everyone everywhere will ultimately want to associate themselves with its prestige. But where does that leave a small-scale creator of bespoke watches back in France or Switzerland or Italy?

OK, let’s transfer these same questions to the world of fine art. Now that Larry Gagosian has 17 — yes, 17 — galleries around the world selling the same roster of 135 artists in total, where does that leave other artists? After all, it’s much easier to buy a name brand (like Jean-Michel Basquiat) than to take an aesthetic and financial risk on an artist not so prestigious, right? Sound familiar? Actually, I am not here to pick on Gagosian or his artists, some of whom are fantastic. Instead, I think that some of the Michelangelo Foundation’s objectives might just pertain to our corner of the art world.

Specifically, the foundation seeks to rekindle public esteem for craftsmanship, to create spaces and opportunities for masters and students to come together, to promote draftsmanship, to save old-school crafts from oblivion, to identify emerging craft professions, and to build links with museums that engage directly with the public. I see many parallels here. Most importantly, the foundation seeks to put human beings back in the center of the conversation, and ultimately to foster a cultural movement built around the values of handmade creativity. Folks, this is especially urgent in our era of artificial intelligence and 3-D printing, when every mass manufacturer is laying plans to replace its human workers with robots. At this rate, it’s only a matter of time before fine art is directly impacted by robots, too. But that does not necessarily have to happen.

Bluntly speaking, the luxury goods world has picked up this flag because their suppliers and workers are declining in number and quality, and also because well-designed luxuries made by real people have every reason to cost more than robot-produced ones, thus giving them a completely understandable competitive advantage.

If you care to muse on how this worldview might help our kind of fine art, visit michelangelofoundation.org and fondazionecologni.it/en, browse around, and see which of their strategies might make sense to copy into your community. Moreover, let’s all work together to remind others — collectors, youngsters, bloggers, curators, whomever — that handmade art really is different, better, more meaningful. The prices we charge are so worth it when you consider all the stories and heritage behind and within what we do.

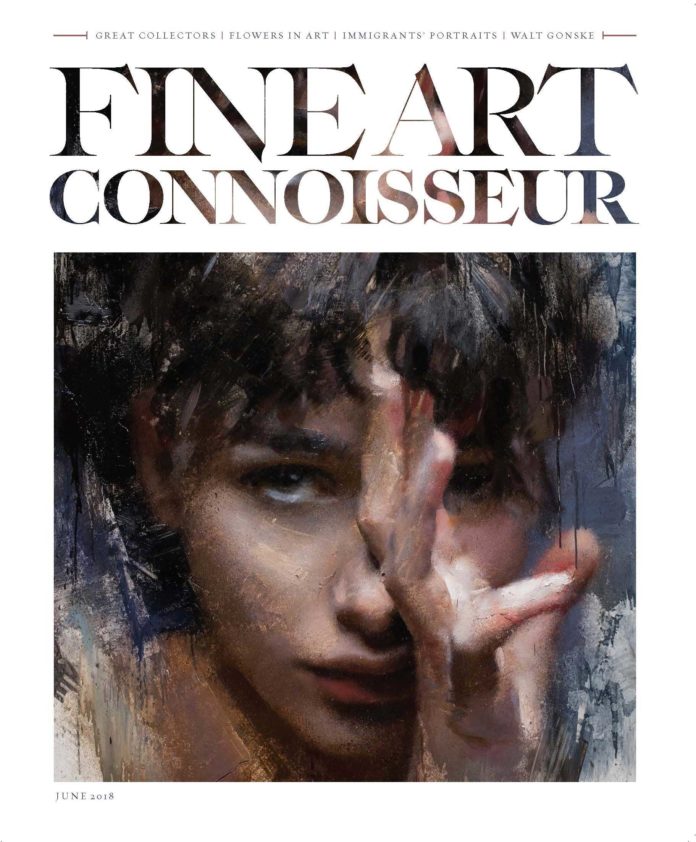

Fine Art Connoisseur May/June 2018 Contents

Something New in Realism

By Vanessa Francoise Rothe

Classical Furniture American Style

By William J. Miller

Celebrating America’s Great Collectors

Walt Gonske Looks Back

By Kelly Compton

City/Country: The Studio Homes of Daniel Chester French

By Karen Zukowski

Gather Ye Rosebuds While Ye May

By Kelly Compton

Great Art Everywhere

Artists Making Their Mark: Three to Watch

Betsy Ashton: Portraying Immigrants’ Stories

By Peter Trippi

Download the May/June 2018 issue here, or subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur today so you never miss an issue.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

[…] fineart […]