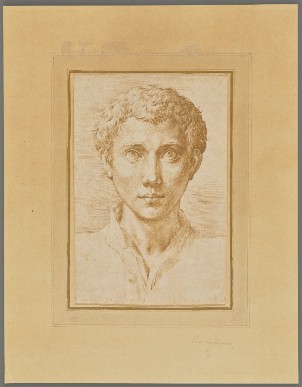

During the Italian Renaissance — the period from about 1475 to 1600 that is often seen as the foundation of later European art — drawing became increasingly vital to the artistic process, as it grew dramatically more sophisticated in technique and conception. Today, Italian Renaissance drawings are considered some of the most spectacular products of the Western tradition. Yet, they often remain shrouded in mystery, their purpose, subjects, and even their makers unknown.

Featuring drawings from the Getty Museum’s collection and rarely seen works from private collections, “Spectacular Mysteries: Renaissance Drawings Revealed” highlights the detective work involved in investigating the mysteries behind master drawings.

“The Getty’s collection of Italian drawings counts among the greatest in this country, and this exhibition will surprise many visitors with how much we still have to learn about these rare works of art,” explains the Getty Museum director, Timothy Potts. “This display, which includes some of our best Italian drawings, provides many insights into the methods curators use to investigate the purpose and meaning of these superlative works of art, and some of the revelations they have disclosed.”

The practice of drawing flourished in Italy during the Renaissance, due to a surge in patronage for paintings, sculpture, and architecture, which went hand in hand with the rise of artists’ studios and a rigorous production process for these works.

Many of the drawings produced at the time tell stories of their creation and the purposes they served, yet sometimes even the most seemingly simple question — who drew it? — is a mystery. Given the ease and informality with which a sketch can be made, its purpose and other information about it must be discovered from the only surviving evidence: the drawing itself.

Clues about the artist can be uncovered by comparing a drawing with the stylistic characteristics of other sheets. In 1995, for example, a Sotheby’s expert looked at “Study of a Mourning Woman” (about 1500–1505), and immediately recognized the distinctive penwork and handling of the drapery of Michelangelo. Subsequent study confirmed this attribution. The Getty acquired the drawing in 2017.

Inscriptions can sometimes also be a useful clue to the artist but should be treated with caution since they often reflect the over-optimistic attribution of a past owner. One work in the exhibition — “Exodus” (about 1540) — features many inscriptions. It took some time and much research to decipher which inscriptions belonged to past owners and which was that of the artist. Eventually, the drawing was attributed to Maturino da Firenze.

Mysteries about the sitter, subject, and purpose can sometimes be revealed by linking a drawing to a painting, sculpture, or print. The purpose of “Two Male Standing Figures” (about 1556) was unknown until 2001, when the work was auctioned and identified as the work of Girolamo Muziano. At that time, it was determined to be a study for figures in an altarpiece the artist painted for the cathedral in Orvieto.

“As I try to learn more and more about these captivating works, I sometimes feel like a detective,” says Julian Brooks, senior curator of drawings and curator of the exhibition. “In the end, this exhibition is the story of what we know, what we don’t know, what we might know, and what we can’t know about these extraordinary works of art and their world.”

“Spectacular Mysteries: Renaissance Drawings Revealed” is on view through April 28, 2019 at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center (Los Angeles, CA). The exhibition is curated by Julian Brooks, senior curator in the Department of Drawings.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

I saw the exhibit of the Renaissance period at the Getty and I loved them. It was wonderful reading your article in this E-mail about them. Art is wonderful, and it just makes the hate in this world go away while reading and looking at the fine are we are exposed to.