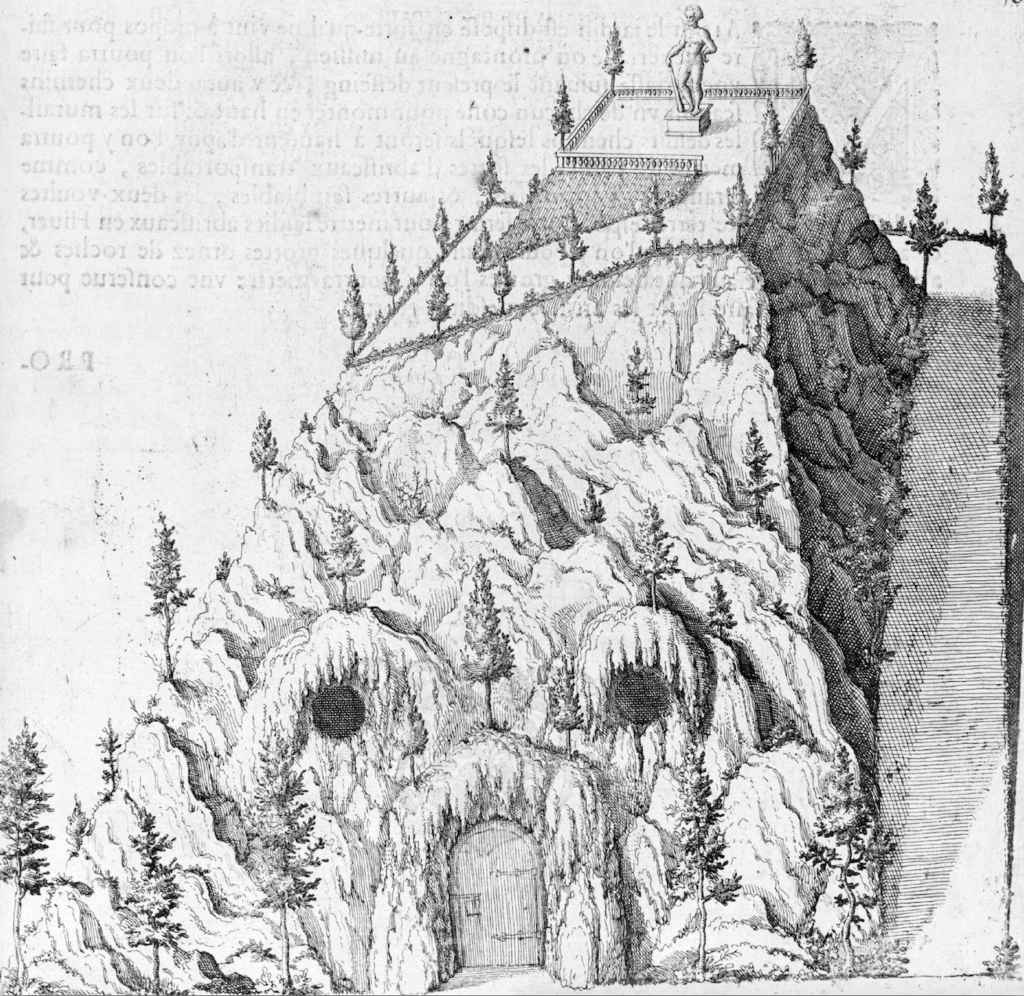

“Mountains and the Rise of Landscape” is the culmination of a curatorial project and a research seminar conducted at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, the latter focusing on the question, How do you model a mountain?

by By Pablo Pérez-Ramos, Edward Eigen, Michael Jakob, and Anita Berrizbeitia:

To ask when we started looking at mountains is by no means the same as asking when we started to see them. Rather, it is to question what sorts of aesthetic and moral responses, what kinds of creative and reflective impulses our newfound regard for them prompted. It is evident enough that in a more or less recent geological time frame mountains have always just been there. It is possible that mountains, like the sea, best provide pleasure, visual and otherwise, when experienced from a (safe) physical and psychical distance. But it might also be the case that the pleasures mountains hold in store are of a learned and acquired sort.

Which is also to say that mountains themselves, for all their unforgiving thereness, are themselves the products of unwitnessed Neptunian and Vulcanian tumults or divine judgment. For the late seventeenth-century theologian and cosmogonist Thomas Burnet, mountains were “nothing but great ruins.” A dawning appreciation of these wastelands appeared in the critical writings of John Dennis. Satirized as “Sir Tremendous Longinus” for his rehabilitation of the antique aesthetic category of the sublime, Dennis expressed the complex concept of “delightful horror.” Mountain gloom was ready to become mixed with mountain glory. More work was still to be done on the literary and philosophical front before the Romantic breakthrough, one high vantage point being the dream of essayist Joseph Addison of finding himself in the Alps, “astonished at the discovery of such a Paradise amidst the wildness of those cold hoary landscapes.”

But a kindred innovation in seeing and feeling was called for in the formation of mountains and the rise of landscape. Mountains, among other earth forms, are both the medium and outcome of still-evolving habits of experiencing, making, and imagining. Architects and landscape architects, mutually occupied with the horizontal surface, have had a touch equally as searching as that of mountaineers and poets in sensing the terrain.

“Mountains and the Rise of Landscape” is the culmination of a curatorial project and a research seminar conducted at the Graduate School of Design, the latter focusing on the question, How do you model a mountain? The installation in the Druker Design Gallery and continuing in the Frances Loeb Library collects diverse objects and scientific instruments, drawings, photographs, and motion pictures of built and imagined projects and presents invitingly challenging modes of seeing (and hearing!) mountains of varied definition. Allied with the work of artists, visionaries, and interpreters of natural and cultural meaning, they propose new and foregone possibilities of perception and form-making in the acts of leveling and grading, cutting and filling, shaping and contouring, mapping and modeling, of reimagining “matter out of place,” and finally of stacking the odds and mounting the possibilities.

“Mountains and the Rise of Landscape” is on view at Harvard University Graduate School of Design through March 10, 2019.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.