“The Symbolist Vision” is on view at Shepherd W&K Galleries (New York) through April 20, 2019. The exhibition is organized by Robert Kashey and David Wojciechowski.

From the catalog (by Kashey and Wojciechowski):

How long has there been a Symbolist vision in the history of art? The answer is, for as long as man has created art.

To choose what is “Symbolist” in art for this exhibition, we surveyed the 19th to the 21st centuries for the Symbolist element, regardless of whether the artists have been categorized as Symbolists or not.

In our survey, many of the works have a religious aspect. The concept of the Sacred and the Profane is essential to the tenets of Symbolism, as it liberates the artist from the materialistic world.

Dream, in which the mind is freed from rational thought, is a source of inspiration in Symbolism.

Horror is often a subject. By facing demons, the artist attempts to tame fear itself.

Death and the afterlife figure prominently in many of the works. Here, the artist confronts mortality and attempts to reveal its secrets.

The erotic is fundamental to Symbolist imagery.

Especially depicting the conflicting attitudes of the 19th century up to the present, human sexuality — desire, fear, hostilities — are all ripe subjects for the Symbolist.

Lastly, many of the aforementioned subjects have been cloaked in mythology, to validate the Symbolist vision.

Symbolists are visionaries who reveal alternate realities and seek out the inner mystique otherwise obscured by the mundane.

The Symbolist Vision Catalog Preview:

Eugène Roger had a short but very promising career. At age 22 he won the second prix de Rome; at age 24 he exhibited for the first time at the Salon; at age 30 he won the first prix de Rome. During his stay at the Villa Medici he painted the portrait of his fellow pensionnaire, the architect Victor Baltard (1805–1874), and he became good friends with the artist Hippolyte Flandrin.

French School

“Medusa,” circa 1900

Glazed ceramic. Height, from top of Medusa’s head to the snakes’ bodies under her chin: 15″ (38 cm); width, from left wing tip to right wing tip: 17″ (43.2 cm); depth, from front peak of Medusa’s hair on the top of her head to the rear: 7″ (18 cm). Impressed on verso: MULLER.IVRY/1,24.

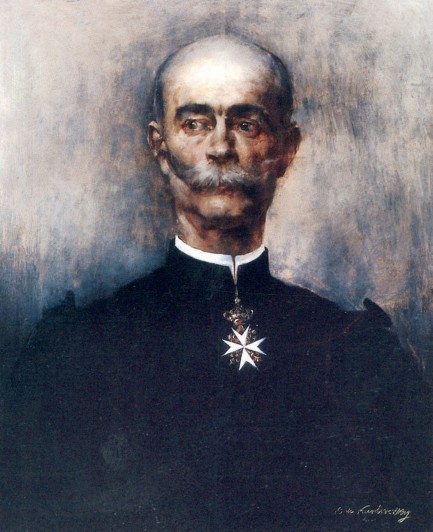

Bertalan von Karlovszky was one of the most sought-after portrait painters in Budapest during the decade before World War I. The present work is inscribed as being painted in Paris, but it shows little resemblance to French portraits of the 1880s. The psychological intensity is similar to works by the Austrian Anton Romako, an outsider in the second half of the nineteenth century. The powerful use of black and the hazily lit background may also reflect the influence of Spanish art, to which Karlovszky would have been exposed in Paris (as extensively documented by the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition Manet/Velázquez, March 4–June 29, 2003).

The plagues in Venice became topical with Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice” (1912), after the disease had struck the city for decades. In the Salon of 1896, Clairin exhibited a painting “The Convalescents Re-entering Murano-Venice” (Les convalescents reentrant à Murano-Venice). It depicts healed women, happily sent back to Venice. The present watercolor depicts sick women being ferried on a gondola to a hospital outside Venice. The present watercolor is clearly related to the Salon entry.

Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer was born in Algiers into a Jewish family. It is not evident when he or his family moved to France. To differentiate himself from numerous other Levys, he adopted a part of his mother’s maiden name (Goldhumer). His education did not follow the routine path of École des Beaux Arts, Rome prize, Salon debut. Instead, after studying with Raphael Collin for a few months, Lévy-Dhurmer became a potter. He was artistic director in the manufactory of Clément Massier on the Côte d’Azur for eight years, inventing new forms and techniques and signing his pieces L. Levy. After a row with Massier he left and went to Italy around 1895. The encounter with Italian Renaissance art was to influence him for the rest of his life.

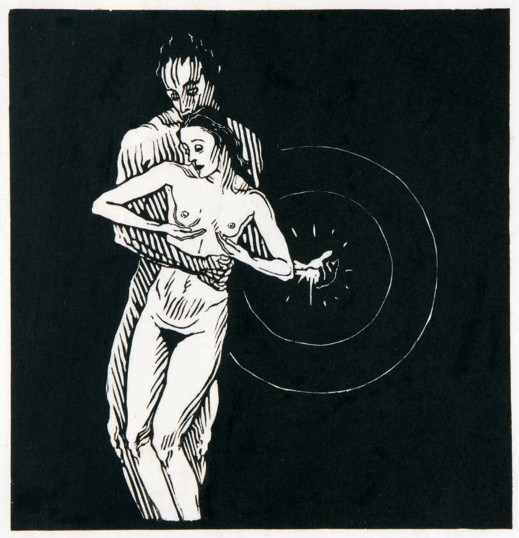

Grete Wiesenthal met Erwin Lang at a ball in 1904. She was soon a welcome member in the Lang family. Gustav Mahler was an often-seen guest in the same house. However, when Mahler cast Wiesenthal in the title role of the Mute Girl of Portici, he stepped on the toes of the ballet director Josef Hassreiter, and the scandal led to the departure of Grete Wiesenthal from the opera ballet. However, this gave Wiesenthal the freedom to pursue her solo career, which led her to Max Reinhardt in Berlin. Erwin Lang worked in Berlin at the same time, drawing designs for the Hebbel Theater and costumes for Grete Wiesenthal’s performances. He also created several paintings of her, as well as a series of woodcuts.

Throughout his career, Kley drew illustrations and cartoons. Once he moved to Munich in 1908, the artist dedicated himself almost entirely to pen line drawing. Combining savage humor with brilliant draughtsmanship, Kley was soon widely known for his wildly capricious and satirical illustrations that he produced for Simplicissimus and Jugend. The present drawing is most likely from his early years in Munich. After the 1910 publication of Skizzenbuch II — the second of two sketchbooks — Centaurs appear much less frequently in Kley’s oeuvre.

Learn more about “The Symbolist Vision” and view the catalog here.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.