How can feelings be put into ground pigment and linseed oil? When a viewer finds a deeper meaning beyond the portrayed subject of a painting, what are they responding to? Mary Pettis addresses this and more in the following essay.

BY MARY PETTIS

“The aim in art is not to imitate the outward appearance of things, but their inner significance.” – Aristotle

Art collectors often wonder what it means when an artist says, “I want to show those who view my paintings not just what I SEE, but what I FEEL.” What are they talking about? How can feelings be put into ground pigment and linseed oil? When a viewer finds a deeper meaning beyond the portrayed subject of a painting, what are they responding to? Are they responding to technical brilliance or something beyond mere paint on canvas? How do artists move from representing how things look to recognizing and rendering visible an inner significance?

Great artists see deeply. I believe each sees beyond the surface appearance. Edgar Payne said, “Art is the reproduction of what the senses perceive in nature through the veil of the soul.” As an artist who also teaches, I am compelled to understand and try to explain this phenomenon. I want to know how, exactly, we transition from the facts of what we see in front of us to the wordless visual poetry inspired from our subjects. In my work I want to capture the inexplicable.

With the following considerations, I offer some pieces of the puzzle that are moving me forward on this quest.

THE TWO GREAT DIALECTS OF ART

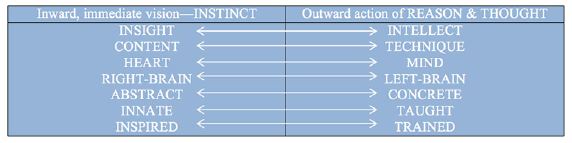

Knowledge comes to us in two ways. First, it comes to us intuitively, through an open heart and receptive senses. Second, it comes to us with disciplined study and training, through the intellect. These are the two ways of seeing. Through the years these dual modes of perception have been explained in many ways.

Through a history of discourse on the riddles of great art, writers and critics of art have called these two camps Colour and Form. They were considered the two great dialects of art, the expressive vehicles for their respective sides of the chart. These two ways of seeing were well represented by nineteenth-century contemporaries Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Impulse and reason, these inner and outer vital elements, form a dance, a pas de deux. It is between these two opposing forces that the Chi, the energy in a work of art, is created. We can recognize, honor, and train both sides, together and separately. Our strengths will often shift heavily to one side, then back to the other side, then back to the other, as we hunger to find balance and improve our wholeness as artists.

The question at hand is: “How do we beyond the surface appearance?” The answer is that we cannot get there through technique and reason alone; we must develop and employ our intuitive, inward vision.

RECOGNIZING OUR INTUITIVE, INWARD VISION

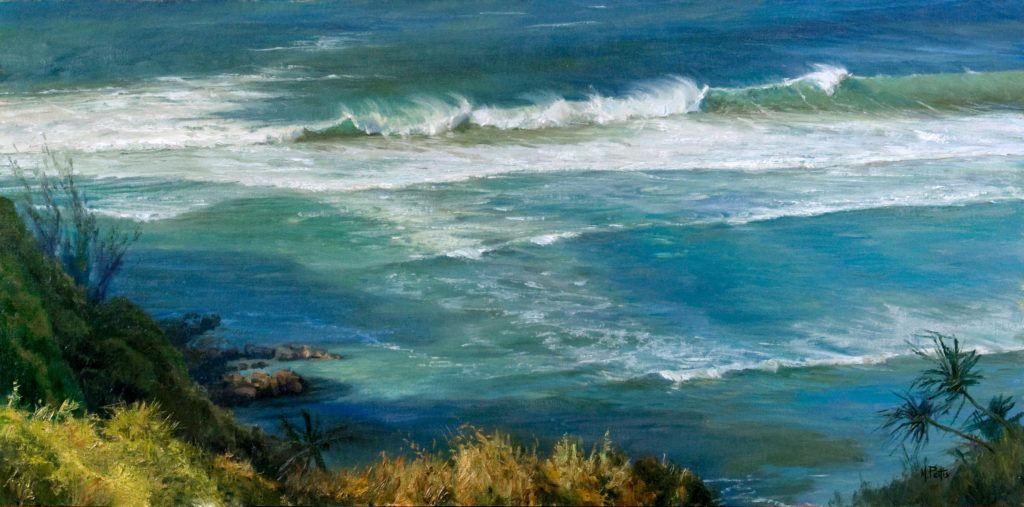

One step in the right direction of understanding the experience of inner vision comes in the first chapter of the early twentieth-century author, L. March Phillipps’ Form and Colour. Phillipps invites us to imagine ourselves on a small ship, traveling along cliffs that descend abruptly into the sea. As we round the promontories each bay reveals a cluster of cottages, fishermen and their boats, white gulls wheeling above, and dozens of other features distinct with meaning and associations belonging to them. They have much to communicate about the life and character of the village. As we notice and think about them, their appearance naturally awakens in the mind a correspondingly observant mood. These forms stimulate the kind of reasoning and comprehension we call intellectual.

But imagine then, as our boat drifts under the shadow of the cliff, we lean over the side and gaze into the depths of water until they absorb our vision. We will immediately be aware of a change of mood or consciousness corresponding to the change in view. Forms become suffused and indistinct, and then cease to exist, and with that change the busyness of mental activity is laid to rest; another set of faculties, the passionate, meditative faculties that apprehend the connections and mysteries of the universe, are awakened and stimulated.

Most of us can identify with this experience. Even if we have not been at sea, perhaps we felt that shift in vision looking deeply into the forest or sky, at a perfectly cut jewel, or into the eyes of someone we love. It is in this state of enhanced emotional awareness that we become more sensitive to the abstract influence of balance, rhythm, and harmony.

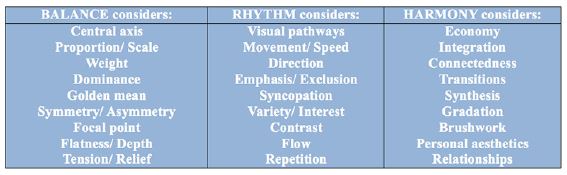

BALANCE, RHYTHM, AND HARMONY

All the arts, no matter the discipline, have in common a desire for the “unity of effect” that is achieved through balance, rhythm and harmony. These instinctive qualities are strongly felt as we form the message of our painting. The message of a painting is the concept, or idea. It is the subject of the sermon, the spark; it is Emerson’s “gleam of light that flashes across the mind from within.”

To truly capture the quality of a place or subject, artists must have a feeling about it beyond its physical appearance. If the artist feels nothing, so will the viewer. To cultivate inner vision, it is important to contemplate what fascinates and stirs us. Is what we are looking at or experiencing a metaphor for something deeper? Something larger: solitude, peace, security, love, interdependence, praise? What is the emotion? What is the inspired content? We must determine the inner significance in order to portray it. I love Emerson’s quote:

“The power in a work of art depends on the depth of the artist’s insight of that object he contemplates.”

In painting, our expressive tools are Line, Shape, Value, Color, Edges, and Texture. Each of these tools can be used, separately or together, to express those things in nature and life that make our hearts skip a beat.

I will submit, as an example, abstract qualities of the first tool, LINE.

Line is here defined as a mark or stroke, real or implied, which defines the contours of a shape or mass, or indicates a visual path. Lines possess potential balance, rhythm, and harmony, according to the artistic intent. Here are seven types of lines that express various emotions:

1. Horizontal, sloping, and meandering lines are calming and bring repose.

2. Vertical lines denote strength and grandeur, nobility, rigidity, or stability.

3. Diagonal lines express movement and action or excitement.

4. Radial lines can draw attention and emphasis to the focus of the painting.

5. Jagged lines are disturbing or distressing or can impart a sense of wariness or danger.

6. Sweeping or spiral lines can direct the speed at which the viewer’s eye moves through the painting.

7. Circular or curved lines can give a womb-like sense of protection, safety, or love.

Simply put, there is an infinite variety of ways artists use the abstract qualities of each of these tools—not just line—to tell the story we want to tell (which I will save for another essay . . .) For now, it is enough to say that great artists slip into a way of seeing where individual parts become a unified whole, and they recognize the character of that whole. Instead of a single tree, they see the outstretched reach of the tree, or the relationships among a family of several trees. They see the flow of the drapery or the vines, the fragility of a child, the gesture of the clouds in the sky.

Great artists identify, through contemplation, what they love, and they know the means and tools to express it. It might be the large sweep of a line or mass, the power or structural rhythms of the large shapes. Perhaps they are responding to the gentle tonality of a landscape in high key values, two vibrant colors dancing next to each other, the softness of edges of every object bathed in cool moonlight, or the sumptuous textures across a field of wheat.

Every other aspect of the painting must be sympathetic with that emotional content. What do I mean by that? Every other detail, element, or added thought must be quieted down or eliminated, to play a subordinate role to that main, inner response!

A painter must be like the choir director who knows how to sense the melody as it intertwines among the sections, while allowing the soloists to shine. The more awareness an artist brings to the orchestration of a piece, the more clearly viewers will understand the message.

As we come of age artistically, we seek to master the two great dialects of art. We learn that Nature is an inexhaustible source of both inspiration and instruction. The deeper we have penetrated the inner being of nature, the greater our desire to recreate the experience. The more methods of expression we possess, the better our ability to communicate our inward vision. We paint solely under the influence of insight and evaluate with the intellect when we set the brush down. It becomes more and more evident that the artistic tools are only the means to an end. That end is to let others into our inner poetic life, to share with them what we see beneath the surface.

Connect with Mary Pettis at marypettis.com.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Click here to subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue

> Join us for Realism Live, October 2020

Articles like ‘The Soul’s Veil:Seeing Below the Surface’ by Mary Pettis usually leave me confused (what in the world are they talking about), disillusioned (if this is what it takes, I’m never gonna get there) and not really understanding what is being said. THIS ARTICLE IS DIFFERENT !! She speaks of the history of art, etc, but then gives a SPECIFIC list of lines (the first in the e list of expressive tools) and the emotions they bring to the painting. FINALLLY something concrete that I can build on! I can’t wait to see her essay on to use the expressive tools to ‘tell the story we want to tell’ !! This is a BREAKTHROUGH article for me – Mary, thanks for writing it so clearly and eloquently !

[…] Read the full article here… […]