How contemporary artist Yuqi Wang, a master of portraiture, discovered Western Art, defied authorities in school, and has answered the question, “Why am I here?”

Portrait of a Portraitist

BY DAVID MASELLO

Yuqi Wang (b. 1958) is looking for the right word. A vintage recording of the great tenor Franco Corelli singing Neapolitan love songs is playing on the phonograph in his Red Hook (Brooklyn) studio, a quiet, contemplative space shot through with beams of sunlight from the west.

“In my portraits, I try to capture something spiritual about the people, their humanity, their interiors — but those are still not the right words I’m after to describe what I want to do as a portrait painter,” Wang says while pointing to various canvases. Although born and raised in China, Yuqi (pro-nounced “Yoo-chee”) Wang speaks English fluently, albeit with an accent, but to find that precise word for his intention, he consults an online Chinese-to-English dictionary.

“Ah, here it is,” he says, holding out the iPhone to show the answer that appears in both English and Chinese characters. “‘Dignity,’ that’s what I want to achieve with everyone who sits for me. Their dignity.”

To look at the many painted faces and figures on the walls and easels of Wang’s loft-like studio is to see the inherent dignity of the men and women he has chosen to depict. Some of the figures are clothed, others are not, and while most are physically beautiful, some wear their years a bit more frankly. Given the way Wang characterizes his subjects, it is not surprising that he cites Rembrandt as among his most important influences.

“Rembrandt tried searching for what was inside a person and putting that on the canvas,” Wang says. “He painted people, yes. But he didn’t always seek out pretty faces or prettily shaped bodies. His figures appear like lighthouses on the sea. You see the real person. The first time I saw Rembrandt paintings, in an art history book as a boy in China, I was very touched. I didn’t recognize the faces he painted as being Western art or Eastern art. They were human faces. That’s what mattered to me.”

Wang came of age as China was convulsed by Mao’s so-called Cultural Revolution, which began in the mid-1960s, and which forced people to shun all things Western, be they political or aesthetic. It wasn’t until Wang was 10 or 11 years old that he saw his first example of true Western art — a black-and-white image in an old newspaper hanging in someone’s window as a makeshift curtain.

He remembers stopping to stare at the image of the figure with long hair and an enigmatic expression. It was Leonardo’s Mona Lisa. “I had no concept of what was or wasn’t Western art at that time, but I couldn’t stop looking, even though the face was a little scary to me.”

Later, in high school, he saw more examples of Western art in textbooks and art magazines. Those images, coupled with a truly revolutionary exhibition of paintings loaned by French museums and mounted in Beijing in the late 1970s, provided Wang with a firm context for the subject matter that has propelled him forward ever since.

He cites Chardin, Millet, Waterhouse, Moreau, the Barbizon School, and Courbet as among the artists and movements that helped forge his artistic identity. “Even today, I keep thinking of the Pre-Raphaelite artists and how powerful it was for me to see their works, especially the red-haired woman in the boat in Waterhouse’s The Lady of Shalott,” he says, referring to the legendary figure who died of unrequited love.

AN EARLY REVOLUTIONARY

Today Wang is one of the world’s acknowledged masters of portraiture, having won prizes and notable commissions, including a grand prize and first place prize from the Portrait Society of America, and a second prize in the National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever competition.

Yet the portraiture for which Wang is famous is not actually the genre he pursued as a young artist. When he attended the Academy of Fine Art in his home city of Tianjin, he was assigned to learn printmaking. “In those days, what you were assigned to study in art school was what you had to study for the four years until graduation. There was no breaking of rules. I was warned that if I kept trying to make oil paintings, which is what I wanted to do, I wouldn’t get my certificate at the end.”

In true revolutionary spirit, however, the precocious Wang defied the authorities. For his graduate thesis, he produced a series of paintings depicting Chinese country life, an echo, in many ways, of the 19th-century French pastoral scenes he had recently come upon and admired. “I must admit, I became a kind of star on campus,” he recalls.

Later, Wang attended Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Art, where he was finally able to experience the thrill and methodology of painting live models, the technique he continues to use whenever possible. There, renouncing the color palette, notably garish reds, that had been promoted by Communist authorities, Wang painted a poignant scene depicting two farmers — a man and a woman just in from the field, dirty and exhausted but inherently noble — a work that earned him a prize. “That painting was dark and its colors muted; it was realistic in ways that paintings in China had not been for many years.”

In keeping with his passion for depicting real people doing real things, Wang later embarked on a five-part series of paintings of a woman. “I remember as a young kid attending a funeral and I saw a girl there in a dress with a white collar. The sight of her and what she was wearing, both on her and the expression she wore on her face, really touched and moved me.” It was from that memory that Wang produced the canvases that traced the complete life of a woman, from girlhood to old age.

From the time he was a boy drawing anything and everything to when he became a student and, later, a teacher, Wang learned the importance of cultivating the right subjects. To be a good — now a great — portraitist requires the earning of trust. The sitter needs to trust the artist for whom he or she sits, often for weeks at a time. It also requires a special vision on the artist’s part — the ability to see into a person.

“As a boy, I taught myself to draw as a way to protect my dignity during the disastrous years of the Cultural Revolution,” Wang explains. “I purposely sought out people I knew would be friendly, willing to let me draw and paint them. My first models were family members, neighbors, and classmates.”

Although China had become a very different place by the mid-1990s, Wang was eager to begin a new metaphorical canvas in his life. Chinese friends already settled in Chicago encouraged him to come there.

“There were four reasons I decided to go to Chicago,” Wang recalls. “One was that I had seen in Paris some of Gustave Moreau’s mythological scenes, and I was especially intent on seeing Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra in the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. I also wanted to see Sir Georg Solti conduct the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, to watch Michael Jordan play basketball, and, maybe, the fourth reason, to see where the Mafia once had so much power.”

While Chicago proved to be the right portal to life in America, Wang continued to feel the pull of New York City, eventually relocating there, where he remains, shuttling daily between his Brooklyn apartment and his studio nearby.

Wang remembers his first tour through the rough-and-tumble, post-industrial landscape of Red Hook; he had heard that the light there — and the low rents — were ideal for artists. “The landlord took me up to the roof of this building, and when I saw the 360-degree views from up there — of Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Statue of Liberty peeking between a church and some factories — I thought, this very setting could be my subject.”

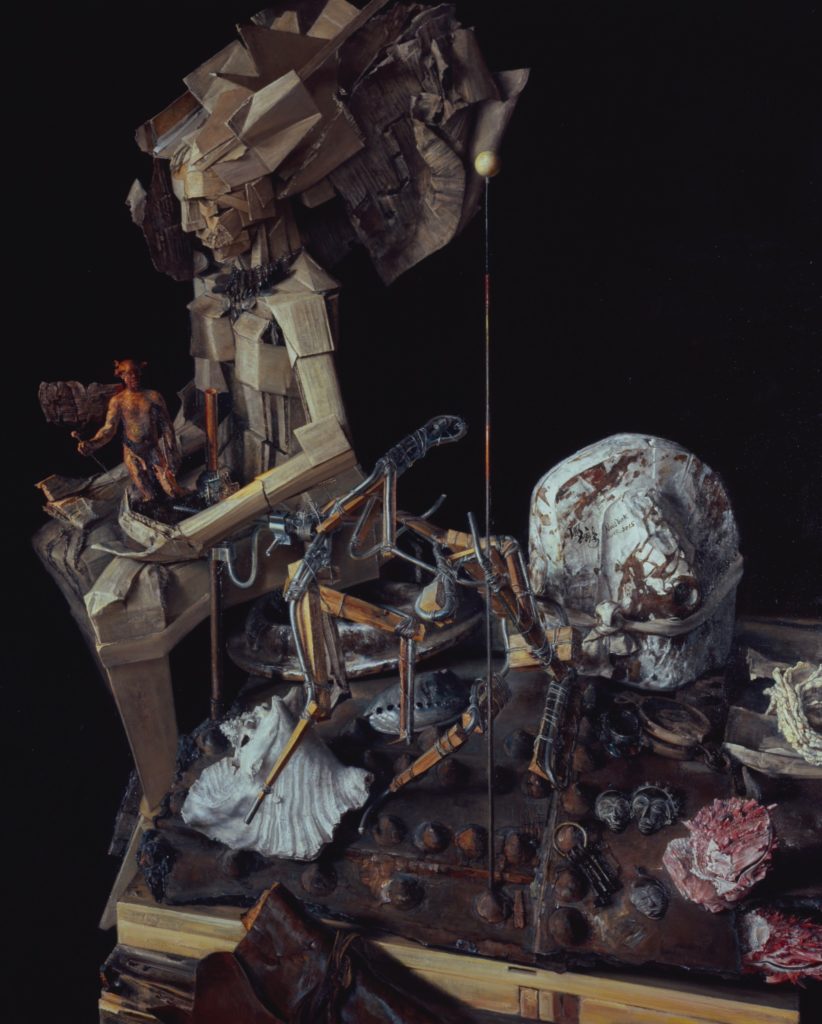

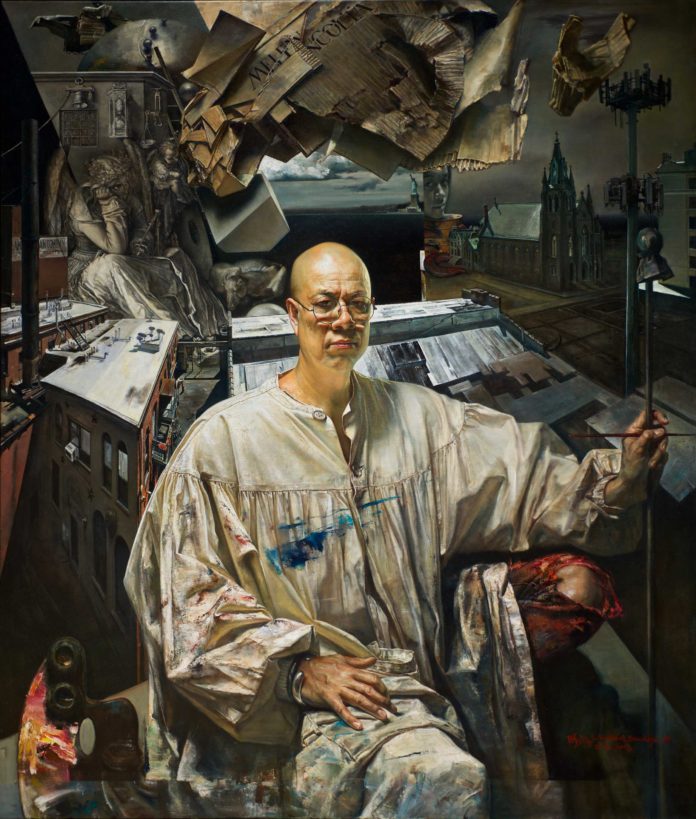

Indeed, to look at “Red Hook Fantasy” (shown at top) his recently completed, and quite magnificent, self-portrait, is to see not only the dignity of the sitter, but also the very surroundings and structures just outside his windows. The factories, the Gothic Revival Catholic church on the corner, the same roof from which he first admired that panorama, the noirish alleyways of Red Hook — all appear as the backdrop to the artist in his paint-smeared smock.

Hovering over this scene — which is decidedly urban and also jarringly post-apocalyptic — is the painted word Melencolia. This references yet another historic master who has influenced Wang: Albrecht Dürer. “I love this word because it evokes the artist’s ‘loneliness,’ which I experienced myself, especially during the Cultural Revolution.”

Wang opens a sketchbook containing some early iterations and ideas for the self-portrait. Page after detailed page reveals a figure, hovering almost angel-like in the background next to him.

Asked about that shadowy figure, Wang replies, “That is Gustav Mahler. I am crazy about Mahler. I wanted to include him, somehow, in a self-portrait because his music is so important to me.” Recognizing, finally, that he was forcing that image onto the canvas in ways that did not feel right, Wang ceded control and instead included an overt reference to Dürer, who represents, perhaps, a more direct artistic bond. Wang’s self-portrait now includes a version of Dürer’s angel from the master’s famous engraving Melencolia I.

ANOTHER PALETTE

In addition to his palette of pigments, Wang works with a musical palette. Whether it’s a recording of Wagner’s Parsifal, a Shostakovich symphony, or, most often, Mahler’s Titan symphony, music accompanies every one of his brushstrokes. “Why Mahler?” Wang asks rhetorically. “Because Mahler is always thinking about the human condition, about philosophy, about religion, about nature, about the meaning of life.”

To further emphasize this musical bond, Wang goes to a corner of his studio and pulls out a canvas that shows a humble house, situated at the end of a long expanse of dense green woods. “This is Mahler’s house in Austria, which I went to see. He had no motherland, really. He was Jewish in a world hostile to Jews. He was always in search of a home, never at home. Even in China, you go from village to village and a person’s accent is different. It marks them as an outsider. I still feel like an outsider, too.”

But feeling like an outsider has advantages for an artist, as it heightens one’s powers of observation. Wang continues to express awe at the people he has met through both serendipity and introductions. One of his most notable models is the Harvard-based scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr., whom he has painted three times; the most formal version hangs at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington.

Wang points next to a large canvas in progress that depicts a beautiful, discreetly nude woman. He was introduced to the sitter, Charlotte de Broglie, by a neighbor who thought she might make a good model. “It turns out she’s a French princess, the real thing,” Wang explains. When she visited his studio days later and saw Wang’s completed canvases, she was the one to offer herself as a model. “She sat for me four or five times. She stated that she couldn’t commission a portrait, but she did hint that once it was complete, maybe her father would buy it!”

In his large portraits, Wang paints not only his sitters’ likenesses, but also their histories. Just as he did with his self-portrait and that of Gates, he has included motifs that reference the princess’s life — for example, an image of Ingres’s 1851 portrait at the Metropolitan Museum of Art depicting the Princess de Broglie. “That is her direct ancestor,” says Wang, pointing to the woman in a shimmering blue gown he has eerily recreated. Also depicted is another relative of the princess, a man who won a Nobel prize in physics. Today the young princess’s gown, trimmed in what appears to be chinchilla, hangs beside the canvas, ready to be worn should she return for another sitting.

Wang continues to study his self-portrait, which he gave himself as a kind of birthday present. While painting it last year, he suffered a serious gallstone attack during which, he says, he “kissed death.” That episode, coupled with world events that have led him to despair — everything from the current U.S. president to Brexit to the European refugee crisis — is what led him to inscribe Melencolia on the canvas.

“One day, I walked to the end of the Louis Valentino Pier, here in Red Hook, and I looked across the water to the Statue of Liberty. I asked myself, ‘What is the value of life? Why am I here?’” By the time he returned to his studio, he knew the answer. “I’m here to be an artist, and every artist’s mission is to speak out.”

Having described this episode, Wang shifts to a cozy seating area in his studio, furnished with a couch and floor-to-ceiling shelves filled with CDs and LPs. He pulls out a vintage LP and puts on Wagner’s Parsifal, the tale of a man’s quest to find the Holy Grail. “Bach, Mahler, Wagner — they help me find the entrance to my soul,” Wang says as the needle drops.

Surveying the many canvases in Wang’s studio, as well as those in private and public collections, it is clear that Wang has found his soul and is sharing it with the world.

David Masello is an essayist on art and culture, a poet, and a playwright who lives and works in New York. This article was originally published in Fine Art Connoisseur, January/February 2019.

Awesome and incredibly interesting life’s lesson learnt as I read the story of this great Artist Wang🥰💗 I live to see his masterpieces and I am thrilled that I can relate with him as an Artist too.

God bless you dearest Wang!

[…] Source: fineartconnoisseur.com […]