An essay on traditional art, written by an artist

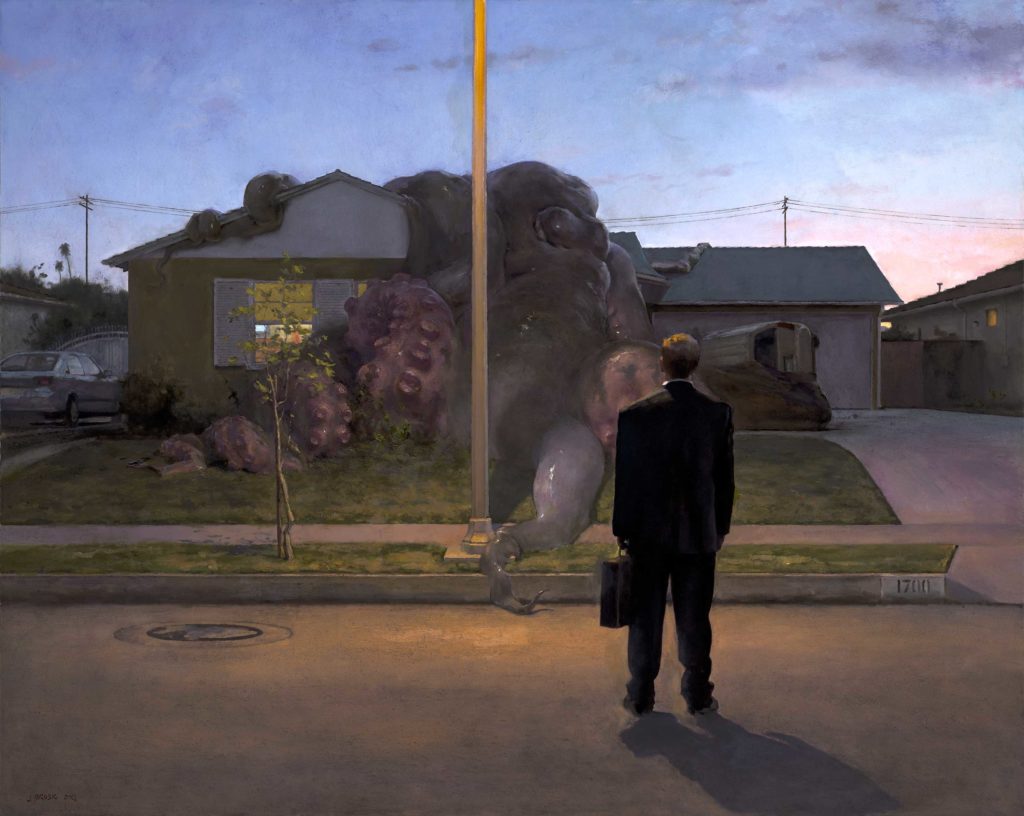

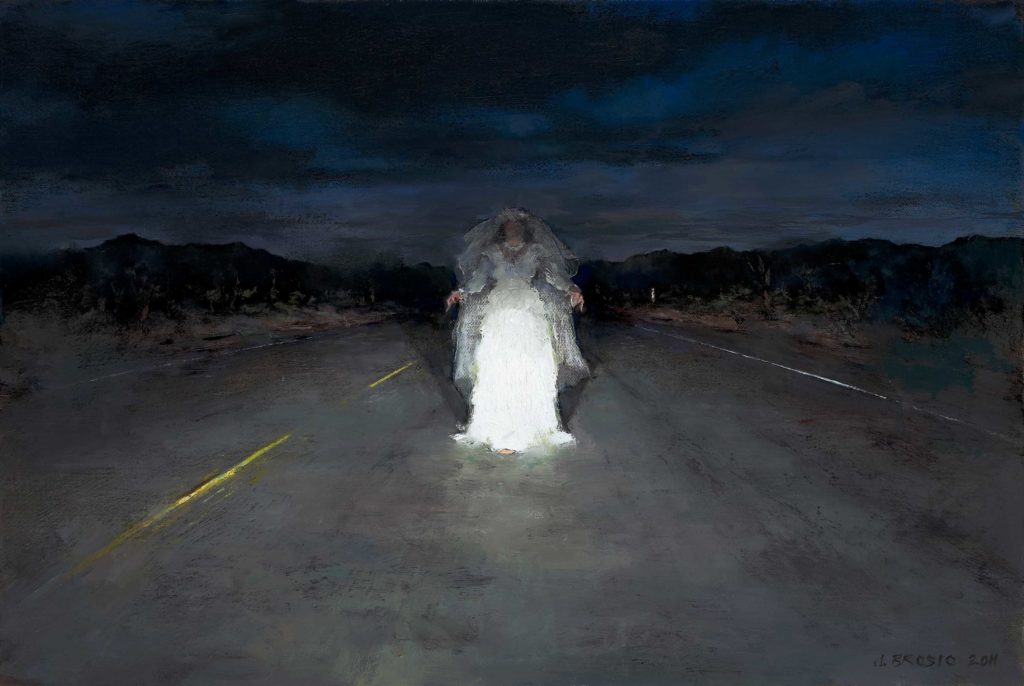

by John Brosio

What interests me most about writing this article is that I don’t know what to say.

In many ways I don’t consider myself a “painter.” Yes, that is what I do, but I don’t think I aspire to it, per se.. I feel that it is more incidental than anything. I am certainly compelled by some of my notions, my opinions, and painting is my means, my way of realizing and exploring those various ideas. My best imagery is the result of a good fight with relationships, proposals, and “what ifs.” Shoot, I almost continued with film in college. As a kid I made my own little abstract films. I even remember asking my mom, when I was in fourth grade, if I could have a hundred million dollars or so to make a movie. She laughed, of course. I think I even sighed and walked back over to my drawing pad to continue with what I was doing.

I am thankful for and enjoy the little realm of exploration in painting that luck and other things have afforded me, but I still don’t feel as if I always fit in. I still see lots of paintings at art fairs and galleries of idealized women walking in the surf, contemplating the intersection of orgasm and meaning. I see paintings of contrived, studio lighting dashed over otherwise majestic subject matter like ranch dressing on Kobe beef. I see thick paint, which of course denotes “meaning.” And oh . . . paintings of floating nudes. Tons of paintings of floating nudes, which assume and depend on that pervasive default fetish for “the figyur.”

And then there’s Warhol (see Robert Hughes).

I guess it was always like this. And will always be like this to some degree.

But must I only gripe?! Not at all. I like some of the things coming out England, like Justin Mortimer. I like Matthias Weischer in Germany (less so the Hockney stuff). These artists are trying something. Wayne Thiebaud still addresses color, mass-produced art, and excess better than Warhol.

I like Tara Donovan too.

But to focus in I am very suspicious of what people are calling “traditional” art. I think that folks have to be very careful with “traditional” because painting in many cases is no longer any of the things it was ever used for. The notion of context goes rather unaddressed I think.

Look, for purposes of analogy, to Galileo (who was born, FYI, three days after the death of Michelangelo). Building that telescope was compulsion. It was need. Only four decades prior the Catholic Church burned Giordano Bruno alive for putting forth essentially what Galileo proved with that little telescope.

That push against comfort, that progress, has palpably continued along in science to this day, where the most learned among us now say that what you are viewing through Galileo’s telescope (or anything else) is actually not entirely there if you are not viewing it directly and collapsing it by way of perception into a wave function. Huh? What? Hard science too now tells us that the universe is probably predetermined to a great degree and that free will is an illusion. Huh? What? These are disconcerting, almost scandalous notions to some, ideas that might get scientists in trouble with any variety of Church.

Or bring them hate mail.

For doing math.

Or for building a telescope.

So if I were to attend a science fair, a supposed meeting of top minds and wonderfully pointy proposals, how disappointed would I be if there were row upon row of homemade telescopes to every one cosmologist?

Just how I feel sometimes is all.

But don’t get me wrong: there is a wonderful culture of amateur astronomers who trade in backyard telescopes. Some have even built their own, if only to go through that first experience, to navigate some of what Galileo felt. That experience is beautiful and elevating. Human and universal.

But no such devices are ever put up anywhere near the summit of exploration.

So. Back to art.

I know a lot of wonderful painters I am proud to call friends. Painters who are trying things. And I see a lot of them struggling in painful competition with rather pedestrian works. One wants so much to find a place to lay some kind of blame for this but that is a mistake perhaps.

All of art and progress is a continuous struggle to elevate us above our nature, and this pursuit can never be abandoned. There will always be a competition with “beautiful” and that is by design. But again, don’t get me wrong: It is in the end a question of sensibilities, no matter what kind of work is being produced. Jeremy Lipking, for example, does what we call “traditional” art. His work is dazzling with regard to the reasons for which it is painted. One can never produce work of that nature, of a traditional sort, and not be responsible to at least that level of aesthetic.

Think about it: Madame Butterfly with world-class singers is amazing. Madame Butterfly with less than world-class singers is silly. “Tradition” has to hold up what has been achieved, not just imitate it or quote it. And the sensibilities have to be there in any successful work, traditional or not. But the folks who buy Lipking have a hard time considering George Herms, Llyn Foulkes, Frank Auerbach, or even David Park, for instance, all of whom champion amazing sensibilities in art that few would call “traditional.”

I wish it were not the case, this latter dynamic. I wish that any consumer could transition back and forth without hesitation between Monet, Turner, and Gustav Klimt on the one hand and artists like Max Beckman, Ed Kienholz, or Kathe Kollwitz on the other.

We are at the point now where no one, in my opinion, can make a great representational painting anymore and not incorporate the contributions of de Kooning, Diebenkorn, and Pollock. Likewise, no one can make great abstract painting without Velazquez and Da Vinci.

I have even seen self-professed Beethoven fans wince upon hearing his late string quartets like Op. 131. They like Beethoven but as soon as he starts trying something I guess he needs to be edited, huh . . .

And there is still a kind of “art smug” in the air as well over some supposed conflict between abstract and representational work, and that is getting to be a little tired, but I digress.

Here is another take on “traditional” just to end this rant:

If someone wants to engage in tradition, to be connected to the Renaissance, they can also participate directly in what the Renaissance has become. Anywhere you find that continuing, compulsive fever of exploration—in aeronautics, film, medicine, cosmology, art, all of it, you can trace it directly back to the first moments of what occurred in Italy. Folks who call themselves “traditional” artists might have a harder time with their label once they realize that 3D filmmaking has as much to do with the traditions of the Renaissance as do paint and brush.

The Renaissance was a time in which art and science were inseparable. Think about creating an art piece during the Renaissance that brings what are now so many disparate disciplines together—top minds of every pursuit—to create a machine that is designed to explore who we are. Think of combining craft, imagery, technology, engineering, and motion, and having it search for who are and where we’re going.

Then perhaps call it the Hubble Space Telescope.

And think on traditional art.

(The above was originally published in Artists on Art, sister publication to Fine Art Today.)

Since writing this the world has hiccupped a bit. All the Climate Change deniers are awfully quiet of late – for good reason.

I hope they stay that way.

And a pandemic has exposed corner-cutting weaknesses across all of human endeavor.

But the Webb telescope has not only just been launched; it is testing well and is expected to afford us the observations and data that could in some way impart the very kind of morale and innovation we need to get out from under some very dire predictions.

Maybe.

Learn more about John Brosio at www.johnbrosio.com.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue