As far as we can tell, neither painting was exhibited publicly, yet both are superb examples of 20th-century American social realism.

By Arthur D. Hittner

On the annals of popular music, there are artists remembered only for a single hit song: Norman Greenbaum’s Spirit in the Sky of 1969, for instance, or the 2000 Grammy Award-winning Who Let the Dogs Out by the Baha Men. The phenomenon of the one-hit wonder also exists in the world of fine art where, seemingly out of nowhere, there appears an extraordinary work by an artist largely unknown, a work so exceptional as to be virtually inexplicable in the context of the artist’s lifetime oeuvre.

What prompts the appearance of these minor masterpieces, and what circumstances explain the absence of comparable works from the same artists? The answers are not readily evident, as we shall discover through two paintings now in my family’s collection. As far as we can tell, neither was exhibited publicly, yet both are superb examples of 20th-century American social realism.

A Glance at Art History and Social Realism

Jackhammer

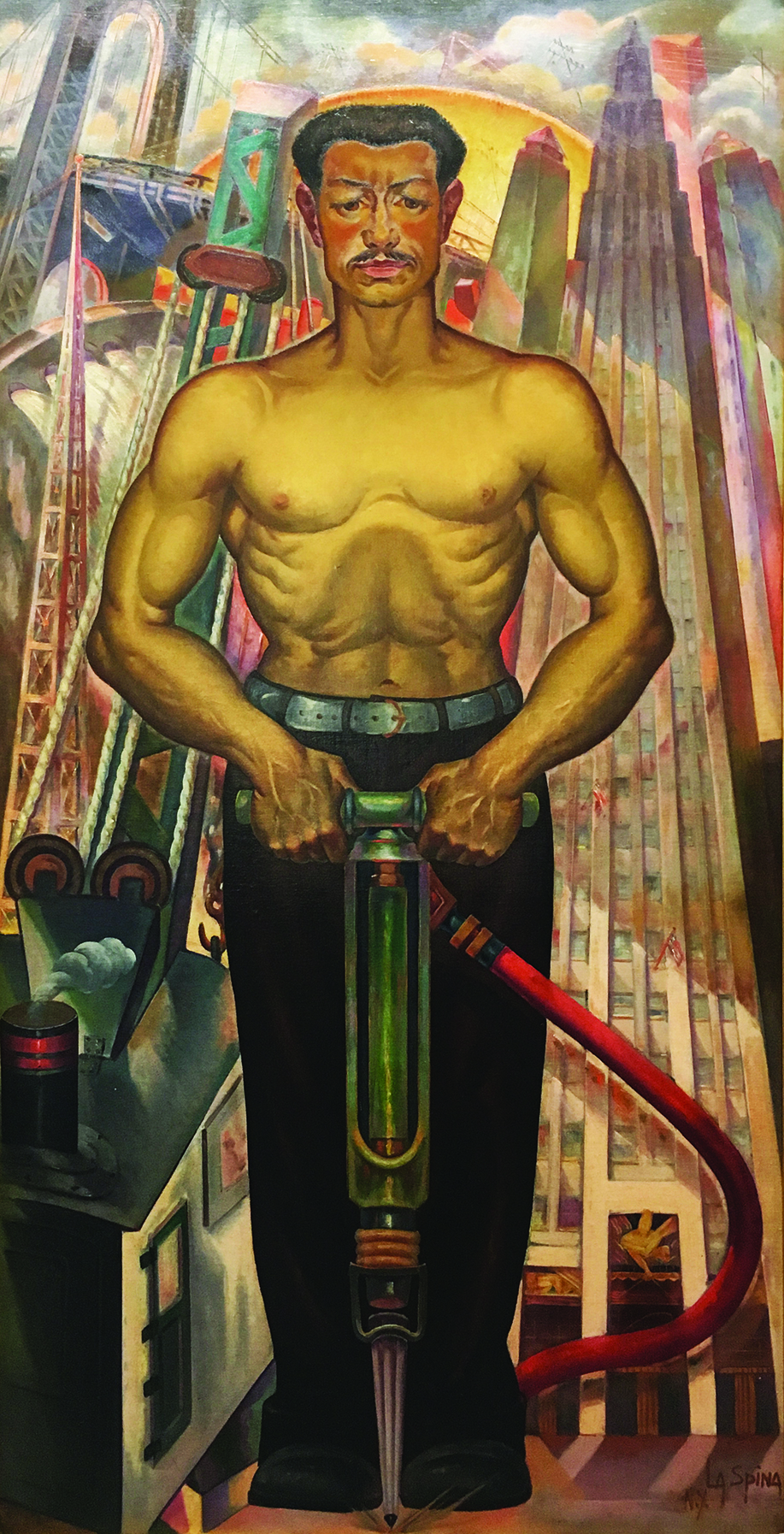

First, let’s consider the painting “Jackhammer,” created in 1932 by Nunzio La Spina (1900–1988). Almost six feet high, it depicts a muscular construction worker, possibly an Italian immigrant like the artist himself, operating a pneumatic drill before an iconic New York City background.

On the left appears the George Washington Bridge (completed the year before), and at right the nearly-finished Rockefeller Center. Flanked by heavy construction equipment and silhouetted by an exaggerated sunrise (reminiscent, perhaps, of the halo frequently seen in Renaissance art), the nameless laborer, as indestructible as his handiwork, is heralded as a hero. It is through his sweat that the architectural and engineering marvels of the city have risen.

So who was Nunzio La Spina? Online genealogical sources indicate that he was born in Palermo, Sicily, at the turn of the 20th century, immigrating to America in July 1914, two months shy of his 14th birthday. His father, Giacchino, had arrived eight years earlier. The artist appears in the 1920 census as a Manhattan resident, living with his mother and three siblings and earning his living as a barber.

A registration card indicates that a John La Spina enrolled in an evening class at the Art Students League of New York as early as 1917, while a 1925 New York census shows a person by the same name (living with his wife, Angeline), both of whom are identified as interior designers.

It is likely that John — listed as a participant in the Society for Independent Artists’ annual exhibition of 1928 — was the same person as Nunzio; it was common for recent immigrants to adopt anglicized names to foster assimilation. In fact, New York Times art critic Edward Alden Jewell noted an exhibition in November 1929 featuring modern landscapes and portraits by “John N. La Spina, a young Italian artist,” at the Little Carnegie Playhouse in Manhattan. (The emphasis on his middle initial is mine.)

Military enlistment records from 13 years later (1942) identify Nunzio as a draftsman of slight build (5’5” and 123 pounds) with two years of high school education. His service, however, inexplicably ended within five months, at the height of World War II.

La Spina’s painting “Portrait of Lillian,” shown at the Salons of America exhibition at Rockefeller Center in April 1934, garnered favorable notice from E.A. Jewell. Indeed, it was one of only a few works reproduced in Jewell’s review (from among 5,000 submitted). Despite this promising recognition from The New York Times, La Spina’s career never gained traction.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that he, like countless others, was unable to sustain himself as a professional artist during the Great Depression. His participation in the Works Progress Administration’s artist relief programs (WPA) is confirmed by the existence of two floral still lifes, one dated 1936 and presently in the collection of the New Deal Art Gallery at the Genesee Valley Council on the Arts in Mount Morris, New York. La Spina’s removal from the WPA rolls in 1937 is confirmed by a Times article in which he is identified as one of a pair of plaintiffs suing for reinstatement to the Federal Art Project. (They contended “that they were dropped without legal cause and that their constitutional rights were thereby violated.”) Although the immediate outcome of this legal action is unknown, La Spina was again employed by the federal government by the early 1940s; he is recorded as having decorated a ceiling in the lobby of Bellevue Hospital’s Psychiatric Building under the Federal Art Project’s aegis.

Not long after La Spina’s death in 1988, Paul Gratz, the proprietor of Gratz Gallery & Conservation Studio (Doylestown, Pennsylvania), acquired “Jackhammer,” along with a group of other La Spina works, from the artist’s estate; a New Jersey framing shop acted as the intermediary. He auctioned off most of the paintings soon after, but retained “Jackhammer.”

Gratz set aside this rolled-up canvas in anticipation of eventually restoring it. Almost 30 years later, he finally did so and then offered the painting for sale in 2017. Most of the few works remaining in La Spina’s estate (including a curious self-portrait) were sold at auction in 2000, but nothing even remotely as ambitious as “Jackhammer” has ever appeared on the market.

Pursuit of Happiness

Equally baffling is the work by Ramond Hendry Williams (1900–1977) assigned the title “Pursuit of Happiness” by its most recent owner. Approximately four feet square, this 1947 painting pulses with energy, reveling in the dynamism of swing jazz culture and the exuberance of post-war America.

Born in the same year as La Spina, Williams pursued a long career as an art educator, ceramicist, and sculptor. Born in Ogden, Utah, he received his Bachelor’s degree from the University of Utah in 1926. He spent three years teaching at Logan High School in Logan, Utah, before continuing his art studies at the University of Chicago and Art Institute of Chicago. Williams taught while pursuing a Master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin before heading up the department of ceramics and sculpture at the University of Nebraska’s school of fine arts from 1931 to 1938. He studied sculpture briefly with the Ukrainian-American modernist Alexander Archipenko at the Chouinard School in Los Angeles (probably in 1933), and was a frequent exhibitor of sculpture and ceramics throughout the Midwest and a regular contributor to the national journal Design.

In 1938, Williams was hired to teach at Texas Technological College (now Texas Tech University) in Lubbock, where he remained in its division of architecture and allied arts through 1946, one year before he painted “Pursuit of Happiness.” In the mid-1940s, he relocated his family to Mission, Texas, near the Mexican border. Little is known of Williams’s career beyond this point, although newspaper advertisements indicate he was teaching ceramics privately in nearby McAllen as late as 1974, three years before his death.

While Williams also painted, few of his paintings are known. An unremarkable modernist scene of prickly pear cactuses now in the Museum of Texas Tech University — along with several canvases owned by his descendants — offer little evidence of the virtuosity visible in “Pursuit of Happiness.”

Although my interviews with Williams’s son and daughter have revealed no specific recollection of this painting, family history hints at a credible source for its evolution. They recall that the family lived briefly in Corpus Christi, a few years before Williams painted Pursuit of Happiness. At the time that city maintained an active naval air station, and it was not unusual for entertainers — both black and white —to perform at dances for non-white guests.

The Corpus Christi Caller-Times of June 29, 1945 reported, for example, that “Clyde Lucas and his orchestra will play … for a dance for negro personnel at the Main Station gym on July 3,” adding that “Louis Armstrong’s band will play for a dance for negro personnel at the NAS gym July 30.” The probability that Pursuit of Happiness depicts such an off-duty event is bolstered by the prominence of the uniformed sailor and the American flag, which together underscore African-Americans’ crucial contributions to the victorious war effort.

Lingering Questions

La Spina’s masterful “Jackhammer” apparently remained with him until his death, more than 50 years after he painted it. Was it a mural spurned by the authorities as too risqué, or a speculative effort that, like most art created during the 1930s, found no ready market? We may never know, but its survival after so many years of obscurity is a stroke of luck. La Spina’s status as a “one-hit wonder” is explained by his apparent abandonment of art following the WPA’s termination in the early 1940s.

The singularity of Williams’s “Pursuit of Happiness” is harder to explain. Although he carved out a successful career in the arts, his focus on teaching — and on ceramics — likely discouraged further efforts at painting. That he managed to produce so fine a painting as this — truly a “one-hit wonder” — remains a matter of fortunate happenstance.

ARTHUR D. HITTNER is a retired attorney and the author of three novels (most recently The Caroline Paintings), two biographies, and numerous articles on topics relating to art and baseball. For details, visit hittnerbooks.com. His extensive collection of WPA-era art appears at paintingtheamericanscene.com.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue