Catherine Murphy: Always Looking

by Daniel Grant

Catherine Murphy (b. 1946) considers herself an “observational painter,” not the photorealist that many of her works might suggest, nor the surrealist that other of her paintings might bring to mind. Perhaps even “observational painter” isn’t the correct term. “I once had a conversation with one of the old realist painters,” Murphy recalls, “and he said, ‘Well, you’re not really an observational painter because you make things bigger than life.’ And I said, ‘Okay.’” Still, she continues, “I call myself an observational painter. I don’t know if other people would, but I do always work from what I’m looking at.”

So the more interesting questions may be, what is this artist looking at, and what does she see? But first, what do we see?

Take the 1991 painting “Persimmon,” which zooms in on the lower half of a woman’s face; we see lipstick smeared on her upper lip. We search for content and meaning, our natural response to realist imagery: was this person kissed by someone who wore the same shade of lipstick? Was she too distracted to apply her lipstick carefully? Does the bright lipstick seek to cover her sadness, which is suggested by her downturned lips? Something seems to be happening here, but Murphy isn’t offering any hints.

Then there’s the 1969 painting “Unmade Bed,” a tumult of colors, textures, and patterns in the sheets, blankets, and bedspread. Behind them is a blank green wall and a window that reveals the greenery of summer. There is a “look what I can do” element to the painting — that question of whether Murphy is at heart a photorealist comes up again — but still we wonder if there is a significance to the bed itself, which suggests a human story. Is someone just not tidy, or was there a reason this person rushed out of bed? Again, we aren’t offered any help from the artist.

“I love the fact that, when viewers look at my paintings, they make up narratives all their own. I sort of think that’s fantastic,” Murphy says. “If you want to spend enough time with a painting that you’re making up your own narrative, that’s cool. I mean, my narrative is just a portal into the possibilities of what happens in life.”

Bring your own associations to that unmade bed, and that’s just as good as anything else. “There are so many things that happen in bed,” Murphy notes, identifying some of the possibilities as sex (satisfactory or disappointing), trauma, or just sleep. “It could be any of those things. I don’t complete the story. I leave it open-ended.”

Establishing the ultimate meaning of Murphy’s art, then, may not be altogether possible. It becomes the viewer’s job to put the pieces together to determine what is going on (or the artist’s intention). This may be easier to do when we look at a number of her paintings rather than just one at a time.

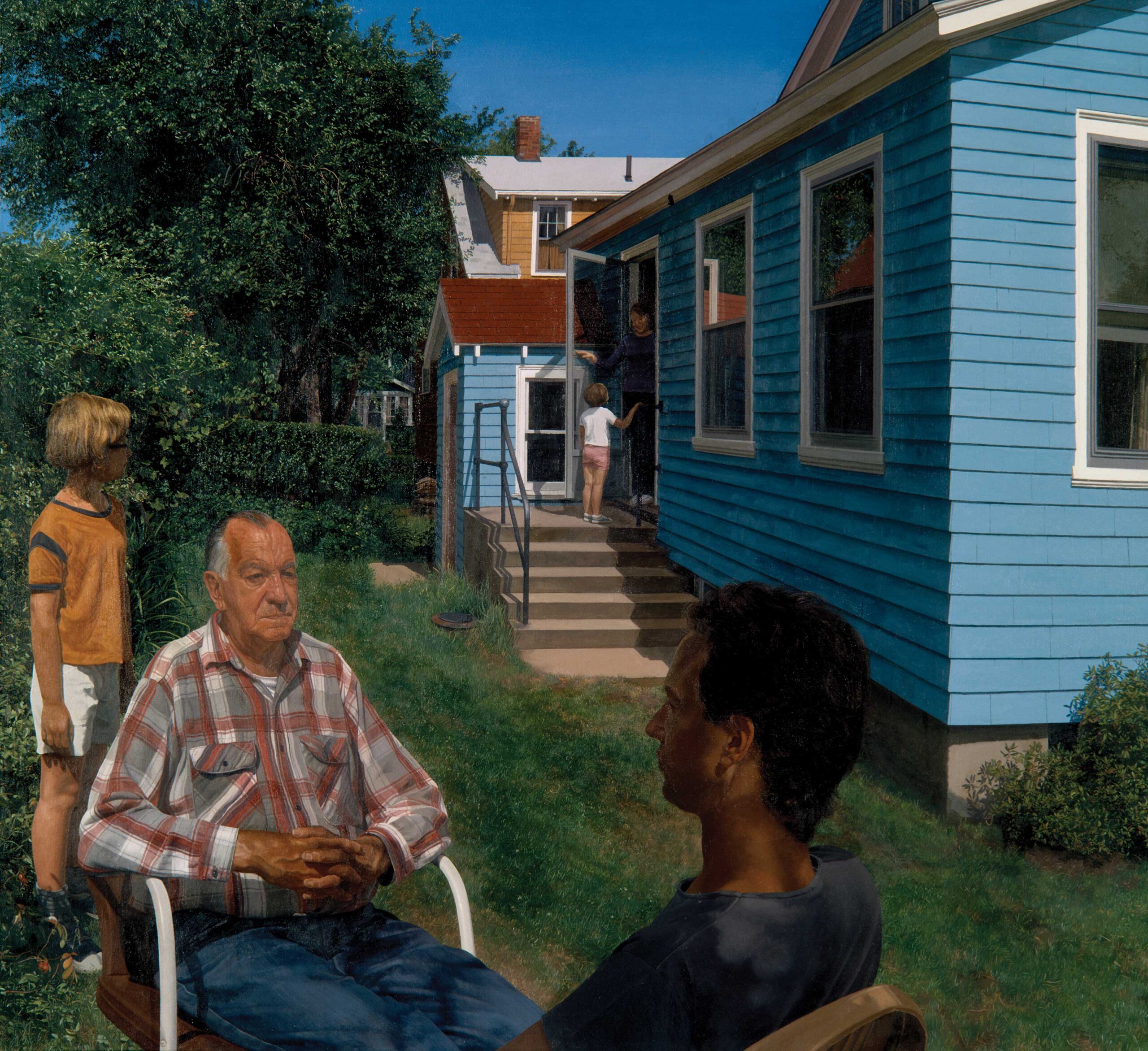

For instance, the first thing one notices in her paintings of people — friends and family members, in many cases — is that no one is smiling, or even communicating. “Frank Murphy and His Family” (1980) features the artist’s father and husband in the foreground, sitting in close proximity but silently looking in different directions.

Even in her 1975 “Self-Portrait with Pansy,” the artist looks in our direction with a sober expression while her cat on the windowsill turns its attention to the city below.

Perhaps one of the glummest images in Murphy’s entire body of work is a 1979 painting of her mother, Catherine O’Reilly Murphy, sitting in profile in a dark-paneled room around midday, cigarette in hand. She stares blankly at an unseen television while a window in the far wall reveals the lush verdure of a summer day.

In 2011, University College London neurobiological researchers conducting brain-scanning experiments found that looking at art triggered a surge of the pleasure-inducing chemical dopamine in test volunteers. Judging from this scene, however, it may also be that the creation of art does not necessarily make either artists or their subjects any happier.

CONTINUE: Read the full article in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, January/February 2023 (download here).