For lovers of the Renaissance and printmaking, the National Gallery of Art is the place to be.

The advent of the printing press signaled a profound moment of modernization because it meant that the proliferation of information — principally academic and biblical — became much more affordable and accessible. It wouldn’t take long, however, for artists to appropriate the new medium, employing the technique in their own unique ways and creating an entirely new form of art. Yet another advantage of printmaking is the ability to reproduce the same masterpiece in quantity, allowing numerous stunning examples to survive throughout the centuries. Even so, perhaps printmaking’s greatest asset would also become its greatest obstacle: Because so many reproductions could be produced from the same plate, and relatively quickly, their aesthetic quality is often undervalued.

Cornelis Cort, “The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr,” 1567, engraving, National Gallery of Art

A current exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is giving viewers the opportunity to appreciate 16th-century Italian prints that were recently acquired by the museum. The museum reports that the prints “represent the principal techniques, types, and phenomena of the period: the extravagant invention of Roman and Florentine artists early in the century; the refined artifice of Parmigianino and his interpreters; the technical advances and incipient naturalism of Venetian printmakers; and the compelling expression of masters associated with the Counter-Reformation, especially the Bolognese. Many of the prints are rare, and most of the impressions are exceptionally fine, of the kind briefly printed and seldom seen.”

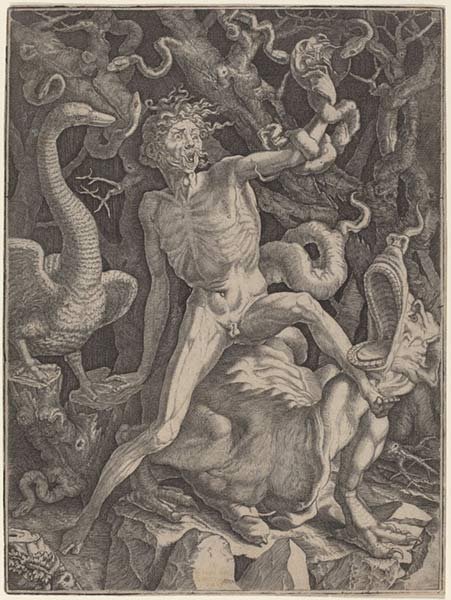

A horrifying but beautifully executed example is Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio’s “Fury,” circa 1524. Based off a similar picture by Rosso Fiorentino, this fantastic print features a gangly, contorted figure at center. Surrounding the man are numerous wild beasts and imagined creatures. Only upon closer inspection is Caraglio’s skill truly illuminated. The printmaker’s attention to detail, hatching, cross-hatching, and dexterity of hand have allowed the image to display an astonishing degree of depth, modeling, and naturalism.

Annibale Carracci, “The Crucifixion,” 1581, engraving, National Gallery of Art

Less demonic but equally moving is Annibale Carracci’s “Crucifixion” of 1581. Although colorless and tightly cropped, the engraving represents the canonical scene in outstanding — but painful — clarity. A toned Christ is presented directly and alone; Carracci has chosen to eliminate ancillary figures, forcing the viewer to concentrate on the most important aspect of the narrative: Christ’s sacrifice. Further, Christ is presented frontally and close to the picture plane, an imposing and powerful presence despite the folio’s size.

No matter their creed, audiences are sure to leave with a lasting impression.

“Recent Acquisitions of Italian Renaissance Prints: Ideas Made Flesh” opened on June 7 and will be on view through October 4.

To learn more, visit the National Gallery of Art.

This article was featured in Fine Art Today, a weekly e-newsletter from Fine Art Connoisseur magazine. To start receiving Fine Art Today for free, click here.