by Sherry Camhy

If you have never heard of metalpoint, you are not alone. A surprising number of art-smart people have not either. Until recently, few schools taught this technique, and fewer art supply stores sold the necessary materials. Only a handful of American museums own examples of it, and those that do rarely put them on view. Major exhibitions devoted to metalpoint are few and far between.

In a National Gallery catalogue essay for an earlier exhibition titled “Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns,” paper conservator Kimberly Schenck helpfully clarifies the terminology: “metalpoint” refers to “drawings created by a tool made of a metal or combination of metals of any type, whereas ‘silverpoint’ designates that the tool was made primarily of silver.” Indeed, artists over the centuries have used not only silver, but also gold, copper, lead, iron, zinc, platinum, aluminum, and brass. It is often difficult to be sure which metal was actually used in a drawing unless that information was passed down from trustworthy sources.

Because silver was traditionally the most commonly used material, most metalpoint images have generally been lumped together as “silverpoints,” but today, investigators can use microscopes, technical imaging, and non-invasive chemical analysis to be more precise.

Silver remains the material of choice because its warm glowing color tarnishes with age to become even more radiant.

Although copper tarnishes too, its coloring varies unpredictably among green, orange, brown, or red hues. Gold does not tarnish, of course; its marks do not look shiny yellow as you might expect, but instead cool gray. Since silver becomes tawny over time, it is sometimes confused with gold, as noted in several of the catalogue entries. Made by the artist Susan Schwalb (b. 1944), the abstract image Strata #295 in this exhibition is a striking demonstration of how silver, gold, copper, aluminum, brass, and platinum can be used together to stirring effect.

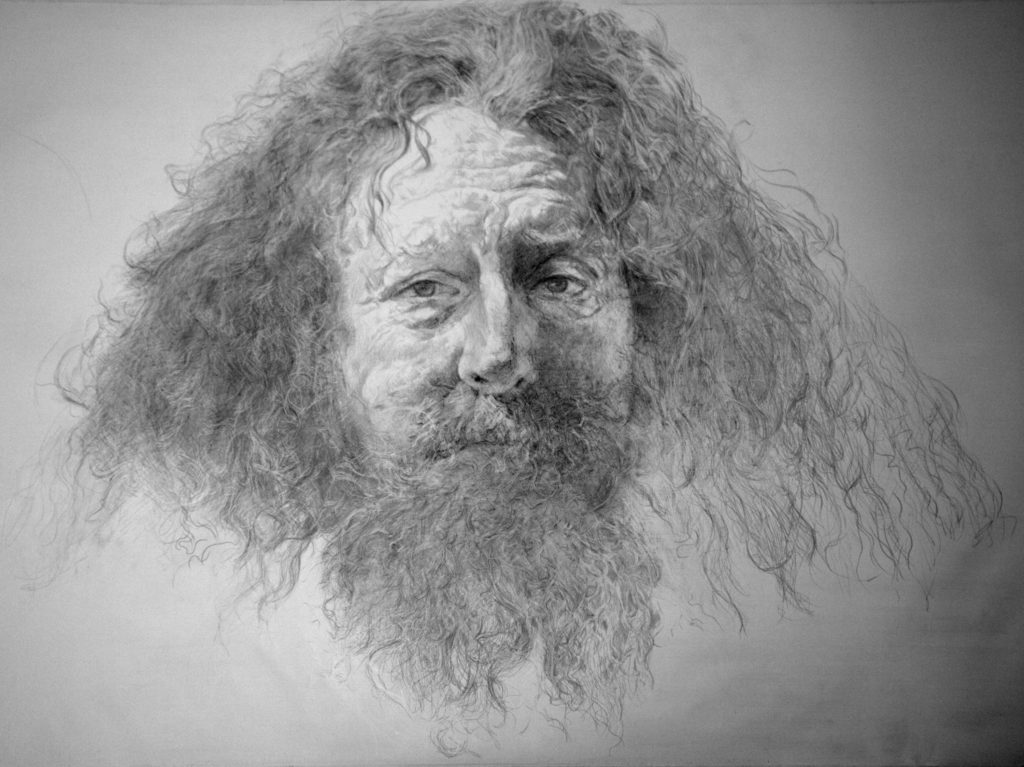

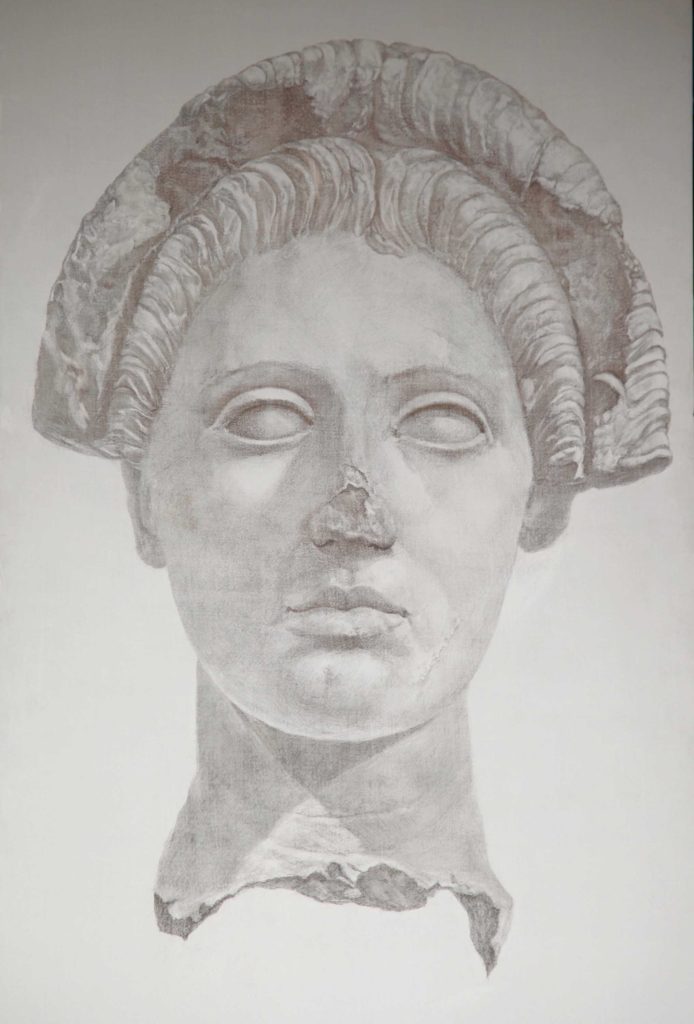

In the past, artists placed a short piece of metal into a stylus, a holder made of wood or ivory. Now, artists usually place the metal into something that resembles a mechanical pencil. In fact, metalpoint was the Old Masters’ pencil, because graphite did not become widely available until the early 19th century. Metalpoints are hard, and the lines they make are consistently even; they do not smudge easily, but they are also very difficult to erase, so each line must be considered carefully in advance. Darker areas must be developed patiently with repeated strokes.

Early on, metalpoint artists began to experiment with mixed media to add a greater range of darks and lights, as well as colors. They did this by toning their surfaces, highlighting with white, applying water media, chalks, and inks, and using blind drawing (cutting through the surface with a sharp tool into the primer tone below). As new materials appear, artists eagerly use them to extend the possibilities.

Today we are free to work on almost any size of two- or three-dimensional surface, prepared with ingredients that make erasing easy, the use of color, texture, and mixed media tempting, and even installation art feasible.

About the author:

Sherry Camhy is an artist, writer, and teacher. She curated a silverpoint exhibition at New York City’s National Arts Club in 2013 and at the Art Students League in 2015. Camhy will be giving a silverpoint workshop at the Art Students League, October 22-26, 2018. For more information, please visit www.sherrycamhy.com.

This article originally appeared in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine (subscribe here).

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

[…] Related: Silverpoint: A Drawing Medium That Remains an Enigma […]