A shared passion for researching the life and art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, and the lessons that can be learned 150 years later.

Mentor and Master: The Enduring Influence of Jean-Léon Gérôme

BY EMILY M. WEEKS

In 1980, the California realist painter Jon Swihart (b. 1954) learned that the Baltimore Museum of Art possessed a group of artists’ palettes. Among them was the well-worn palette of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), the French academician Swihart had long admired. Impressed by Swihart’s excitement during their phone conversation, a museum registrar kindly measured and photographed the historic palette for him.

Within a few weeks, Swihart had an exact replica made and still uses it to this day. “My palette has become a sort of talisman,” Swihart explains, “and I feel a deep connection with Gérôme while holding it.”

Bottom: Jon Swihart’s wooden palette, 11 x 16 in.

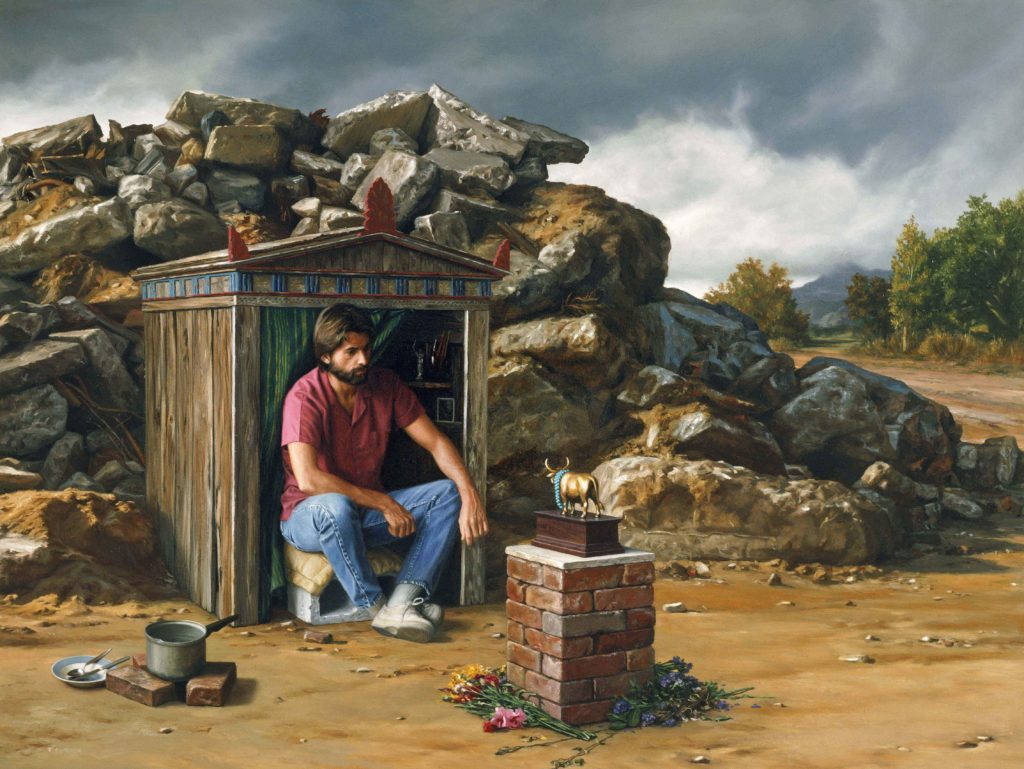

Swihart’s enthusiasm for Gérôme is evident throughout his Santa Monica studio. His paintings, inspired by some of the master’s best-known compositions, are propped on easels, their surfaces as smooth and painstakingly precise as Gérôme’s slick, detailed originals. The door of Swihart’s studio is similarly revealing: an Arabic phrase is painted across the chestnut-colored wood, lifted directly from the inscribed portal that appears in an early Gérôme painting of a Sudanese guard. (Written in Ottoman script, this quotation from the Quran reads “Your Lord is indeed the Creator of All, the All-Knowing.”)1

Scattered throughout Swihart’s studio — and also in the comfortable home he shares with his wife and fellow artist Kimberly Merrill — is a selection of Gérôme paintings, drawings, and sculptures the artist has acquired over the years. They, along with a wealth of related ephemera, form a thoughtfully curated collection that is both museum-like in quality and, in its deep and visible influence on Swihart’s daily life and artistic practice, animate and approachable as well.

”Although I regard all the Gérômes in my collection like holy scripture,” Swihart muses, “one of my favorite pieces is an early study of a draped figure. I love this drawing because it is so intimate and so telling, like a window into the artist’s mind and soul. It embodies what I believe is at the heart of Gérôme’s work, and what I strive for in my own — sincerity, reverence, restraint, and economy of form.”

AWE AT FIRST SIGHT

Swihart’s interest in Gérôme began in 1972, when he found at the Santa Monica library the catalogue of a retrospective at the Dayton Art Institute.

“I had never heard of Gérôme and was instantly enthralled by his paintings,” Swihart recalls. “This was the mentor I had been seeking!”

Determined to learn more about this 19th-century master, Swihart was surprised to find that little research had been undertaken: “At that time, there was virtually no information available on Gérôme, which fueled my obsession and curiosity all the more. Then a few scholarly articles began to appear, all written by Gerald M. Ackerman [1928–2016], who, I later discovered, lived near me in California. The first time we met, we spent the entire day meticulously going through his massive Gérôme archive.

“It was one of the most powerful experiences of my life, and I left that evening with my arms full of irreplaceable documents that he generously allowed me to borrow. That was the beginning of a long friendship with Jerry, in which we shared our passion for all things Gérôme.” (Swihart’s geographic serendipity would continue; he only recently discovered that a neighbor and collector of his art — a friend for 30-odd years — was in fact the great-niece of Fanny Field Hering, Gérôme’s contemporaneous American biographer.)

Though remarkable in many ways, Gérôme’s powerful influence on Swihart, a practicing American figurative painter, is not without precedent. Indeed, during the course of Gérôme’s long and prolific career, no fewer than 150 American artists passed through his Paris atelier, learning the nuances of his academic style and finding inspiration in his extensive travels and exotic subject matter. (Gérôme traveled throughout the Middle East between the 1850s and 1880s, accumulating a vast library of sketches, props, and souvenirs that were used for his later paintings.)

Among the most famous of these students were Frederick Arthur Bridgman, Thomas Eakins, Edwin Lord Weeks, and J. Alden Weir, who each took from Gérôme’s training elements they adapted for their own idiosyncratic purposes.

For Swihart, the lessons from Gérôme have been many and varied — and each equally profound. “In the wake of Abstract Expressionism in the 1970s and ’80s,” Swihart explains, “art schools frowned upon developing any skills in drawing and painting. So, with no real support or guidance, my approach to creating realistic art was unfocused and random. But the discovery of Gérôme gave me a clear goal of what I wanted to achieve.”

He continues, “Gérôme is a great mentor because countless pencil drawings, oil sketches, and abandoned half-finished paintings have surfaced thanks to his growing popularity over the last few decades, providing numerous opportunities to observe his creative and decision-making processes. It’s actually inspiring to watch him struggle from a mediocre beginning until he creates a masterpiece. This kind of visible agonizing — the persistence and effort we see — makes Gérôme very human and accessible to me.”

Swihart’s admiration extends to the most specific aspects of Gérôme’s technique. He has adopted the master’s practice of developing and improving an idea through a series of sketches, which culminate in a resolved oil study that, in Swihart’s words, “allows for total concentration when executing the final painting.”

One such oil study by Gérôme, among the last to be finished before his death in 1904, holds a special place in Swihart’s home. Displayed in characteristically thought-provoking fashion, with complementary or amusing objects nearby, “Lion in the Desert” both educates and offers a continual source of inspiration to Swihart, who sees beneath its brilliant hues.2

“I use the same orderly painting process witnessed here,” he observes, “first toning the canvas or panel with an imprimatura, or preliminary stain of color, then making a precise drawing over it, adding a thin roughed-in underpainting, and finally, putting in the fully finished upper layer, with only one area being completed at a time. I also use Gérôme’s oil-resin painting medium.”

A MASTER WHO LOOKED BACK AND AHEAD

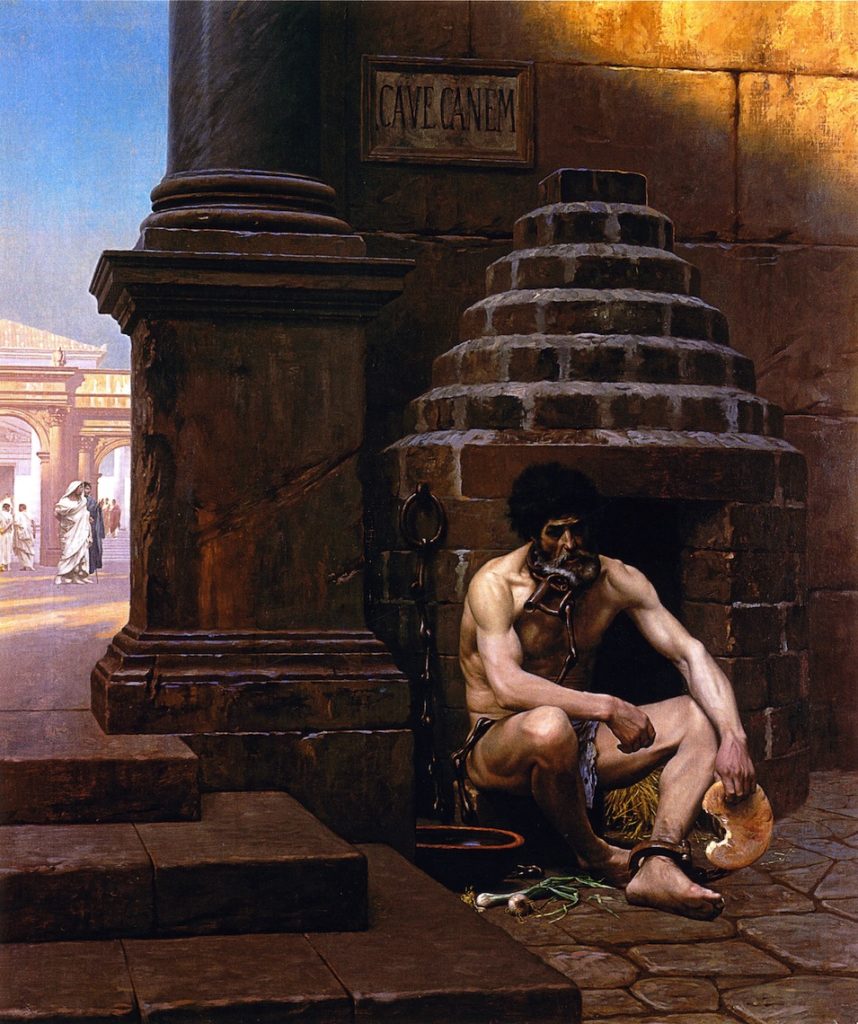

Such dedication would surely have been appreciated by Gérôme, perhaps the most disciplined artist of his day. Born in Vesoul, France, in 1824, Gérôme began his career as a leader of a group of young painters studying in Paris with Charles Gleyre and Paul Delaroche.

Inspired by Greek art and the recent discoveries of frescoes at Pompeii and Herculaneum (sites that Gérôme visited), as well as by contemporaries’ love of narrative and a modicum of scandal, these Néo-grecs painted antique genre scenes with a salacious touch and a distinctive, sun-drenched palette. Such subjects were the perfect vehicle for Gérôme to display his lifelong love of drama, theater, gesture, and costume, and to indulge his developing and seemingly divergent interests in color, light, and the archeological reconstruction of the classical and, later, Eastern worlds.

Gérôme’s path to Orientalism — the genre for which he would become best known — began in 1856, when he first traveled to Egypt with a group of colleagues and friends. Subsequent trips to the region expanded his repertoire of subjects, and confirmed — at least in contemporaries’ eyes — his talents as an ethnographer and his reputation as a privileged witness to all aspects of Middle Eastern life.3

In addition to these firsthand observations, and the artifacts and decorative objects he brought back, Gérôme made great use of the latest technology and scholarship to create his art. An ardent supporter of photography, he accumulated a massive archive of amateur and professional photographs, which he added to his bookshelves of academic publications on Islamic culture, architecture, and design.

Though his subjects are more domestic, Swihart arrives at them through a similarly rigorous investigative process, and via many of the same means. Photographs — most taken by Swihart himself — provide a practical solution to the demands of his hyper-realistic style, releasing his models from what would other-wise be an endless marathon of sittings and offering a means by which to study even the most minute detail. (Swihart is quick to correct anyone who compares his work to photography, however, explaining that it is instead, much like Gérôme’s, “an intuitive blend of fidelity to reality and poetic license that just happens to resemble a photo.”)

Travel and bookish research also contribute directly and indirectly to Swihart’s artistry. During one of his many trips to France (his “magical faraway land of dreams”), he embarked on a pilgrimage of sorts. It included measuring and drawing the floor plan of one of Gérôme’s studios (now an office space); visiting the room in which the artist was born and the street corner where he waved farewell to his dining companions on the night he died; and visiting descendants of the artist, who shared their stories and the artworks they inherited to help bring the master to life.

The sum of these experiences and the logs of quantifiable data — which constitute an archive that, in many ways, rivals Ackerman’s — add a gloss of erudition and an element of history to even the most modern and “popular” of Swihart’s paintings. His 2014 portrait of the legendary cartoonist, artist, and fashion designer Paul Frank, for example, traces its lineage to the penetrating figure studies and society commissions produced by Gérôme and, rather cleverly, to a dynamic portrait of Gérôme at work, painted by his peer Fernand Cormon and also owned by Swihart.

It is this connection with the past — between the works Swihart collects and those he is inspired to create — that grounds and guides him at every turn. “The artist,” Gérôme once advised his students, “should be a poet in conception, a determined, honest, and sincere workman in the execution.”

As a young man, Swihart once taped this quotation to his studio wall. Ever since, Gérôme’s words have become an all-embracing philosophy, resonating as powerfully today as they did more than 150 years ago.

EMILY M. WEEKS is an independent art historian and consultant for museums, auction houses, and private collectors in America, Europe, and the Middle East. Her areas of expertise include Orientalism and 19th-century British and European visual culture; she is also the acknowledged expert on the artist Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Endnotes:

1. Surah Al-Hijr 15, verse 86.

2. A more complete version of this painting is in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo.

3. Today, the “realism” of Gérôme’s Orientalist works is rightly called into question.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Click here to subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue

I was disappointed that there was no mention of the wonderful collection of Gerome in the Haggin Museum in Stockton, California.

I was lucky enough to meet Jon when he lectured at the Getty, during a display of Gerome art. Jon is a very nice gentleman who invited me to lunch at his home, and allowed me to see his collection. I had just stumbled upon a Gerome bronze, Caesar Crosses the Rubicon at a swap meet. I snapped it up for the princely sum of $15.00. Jon was good enough to authenticate it, and have a lively discussion of Gerome and his son in law’s art. Oddly, Jon and I knew a few people in common. I’m not an artist, but a sign painter and contractor since age 13.