How painting on location has changed for one artist, in multiple ways.

BY NANCY BEA MILLER

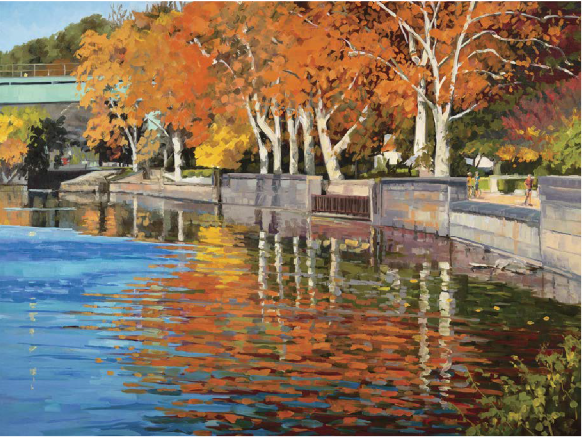

For many years, the urban landscape paintings of Elaine Moynihan Lisle (b. 1954) have gloried unabashedly in bright summer days. Using bold colors and lively brushwork, the artist has infused energy into her world of flowerbeds and leafy trees contrasting with red bricks, colorful awnings, and the pure blue skies soaring above them. “It has been hard for me to paint a rainy or cloudy day,” Lisle explains. “When there is no sun, I have always sought the silver lining, or the bright spot hidden in a bank of clouds.”

Lately, however, Lisle has been focusing on other seasons and times of day. Her family weathered two tragedies in 2019: her mother lost a difficult battle with ALS, and then a beloved sister-in law died at a relatively young age. These experiences inevitably influenced Lisle and her art: “I’m still an aesthetic optimist, which I equate with saturated colors and light,” she says, “but perhaps that optimism is being tempered. I’ve developed more of an appreciation for all seasons, from dawn to dusk. A sunny summer day is not necessarily the only beautiful moment.”

Lisle says this realization is due in part to her growing participation in the national plein air movement. “Plein air competitions have pushed me to paint more quickly, even when I’m not in the mood. Whether it’s rainy, chilly, or hot, you must be out there when you’re competing. You rise to the occasion and it stretches you in a good way. These experiences have also made me push harder once I get back to the studio.” Just for example, Lisle cites a nighttime event during Maryland’s Plein Air Easton as having opened her eyes to the aesthetic possibilities of darkness.

Painting from nature is hardly new for Lisle. Her maternal grandfather, Russell Barnes, was a landscape architect who loved to sketch. “I visited my grandparents’ place in New Hampshire in the summer; my grandfather and I would paint together and he’d give me tips about things like aerial perspective. He would say, ‘Put more blue and white in the distance to push those mountains back, Elaine!’ Being with someone like that encouraged me by example. He was always observing, trying new things.”

One of Lisle’s own new things is a 36-by-30-inch painting titled “Rittenhouse Snow.” It depicts Philadelphia’s most prestigious square glowing at sunset and twinkling with street lights, all covered by fresh snow. The subtlety of its colors and the interaction of its various light sources offer a visual feast.

Lisle recalls, “When my husband and I turned the corner and walked into Rittenhouse Square, I was absolutely knocked out by the colors. The snow had transformed a familiar landscape into something softer, different.” She snapped as many photos as possible with her smartphone, regretting that she “couldn’t start painting the scene right at that moment.”

Back in her studio the next day, Lisle painted a small study from memory, augmented by her photos. “I was trying to remember the feel of the color rather than going strictly by the photos. Photographs never exactly capture the color anyway. In my memory, the sky was brilliant coral and the lights were like glowing coals in the blue shadows of the snow.” Lisle realized then that she could indeed recreate what had struck her so viscerally.

“Broad Street Banter” is another painting that offers a slightly oblique view down Broad Street toward Philadelphia’s City Hall. In the foreground people converse under the red banners of the University of the Arts. Though this painting depicts a sunny day, there is a captivating tension in how the figures interact.

“I just loved those guys,” Lisle laughs. “Sometimes I put in people, sometimes I don’t. Often I will take someone from one scene and insert them into another. I am not slavish to a photographic moment, and figures must add something to the ‘story’ in a real way.” This lively painting is the by-product of a commission Lisle received for a more typical view of City Hall. “I finished the commission, and then I got to paint this for myself,” she explains with evident satisfaction.

THE WINDING PATH HERE

Lisle grew up in rural Storrs, Connecticut, and now lives in a Philadelphia suburb. Why, one might well ask, does she feel so drawn to urban scenes? The answer stretches back to her youth. Lisle was helping her father clean out his house and found one of her sketchbooks from high school. It was filled with perspective studies of streets and buildings, apparently drawn for the fun of it.

“Understanding perspective was such a light bulb moment for me,” Lisle recalls. “Drawing a city street with buildings marching away into the distance was so much fun!” Unlike many artists, Lisle has always had a mathematical side: “I considered studying architecture,” she says, “but painting won out. Still, whenever I look at anything, I am studying the interactions of planes. I break things up into pieces, shapes of colors. It’s the way I perceive things.”

One of Lisle’s favorite professors during her two years of post-graduate study at Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was the late Murray Dessner. “As an abstract painter, Murray was always talking about edges, how paint edges meet and where different colors touch each other. Until then I was not so focused on how these pieces make a pattern.”

Lisle had previously earned a B.F.A. at the University of Pennsylvania, including some independent study with the late Neil Welliver, who was renowned for his large landscapes, often made en plein air. Lisle remembers, “Under his influence I was taking my large canvases outside. I had been trying to be more abstract up to that point, interpreting the urban landscape in terms of shapes and color; it was the ’70s and abstraction was typically the goal for young artists. But then, when I saw what Neil was doing, I realized that it was okay to be a realist. What a relief.”

Like so many landscapists before her, Lisle prepares for her larger works by painting “a small oil sketch on site. Based on its information, as well as on additional photos I take on site, I then create the larger piece in the studio. Sometimes I go back and take more photos, or do another color sketch. I might decide that I now want to see what was behind a parked truck, or if a slightly different angle might work better. The larger painting never just replicates the on-site sketch. It must have its own spirit.”

Learn more about Elaine Moynihan Lisle here.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue