Figurative art and portrait paintings >

The artist Duffy Sheridan (b. 1947) seeks “to magnify the dignity of the human spirit, and also the singular beauty of all things.” He explains, “When people look at one of my paintings, I’d like them to see that humans, indeed, are noble beings.” He achieves this by capturing in paint “a look, a movement, a casual occurrence that enshrines power and grace in time.”

Amazingly, Sheridan has been able to create his compellingly life-like paintings without formal training, except for a few basics proffered by his father, who was a traditional painter of marine scenes. “But if I had it to do over again,” he admits, “I probably would have gone to art school, as it would have saved me considerable time.” As it was, he taught himself by looking in all directions. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Sheridan was living in the Bay Area, managing a grocery store by night and selling portraits by day. He married his wife, Jeanne, in 1969, and two years later they became members of the Bahá’í Faith.

“There is a direct relationship between what I do as an artist and what I believe as a Bahá’í,” Sheridan notes. This proactively international faith was formalized by the Persian thinker Bahá’u’lláh (1817–1892), who wrote that “the earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.” His belief that all of the world’s religions have been stages in the revelation of God’s will and purpose for humanity informs the Sheridans’ outlook generally, and Duffy’s art specifically.

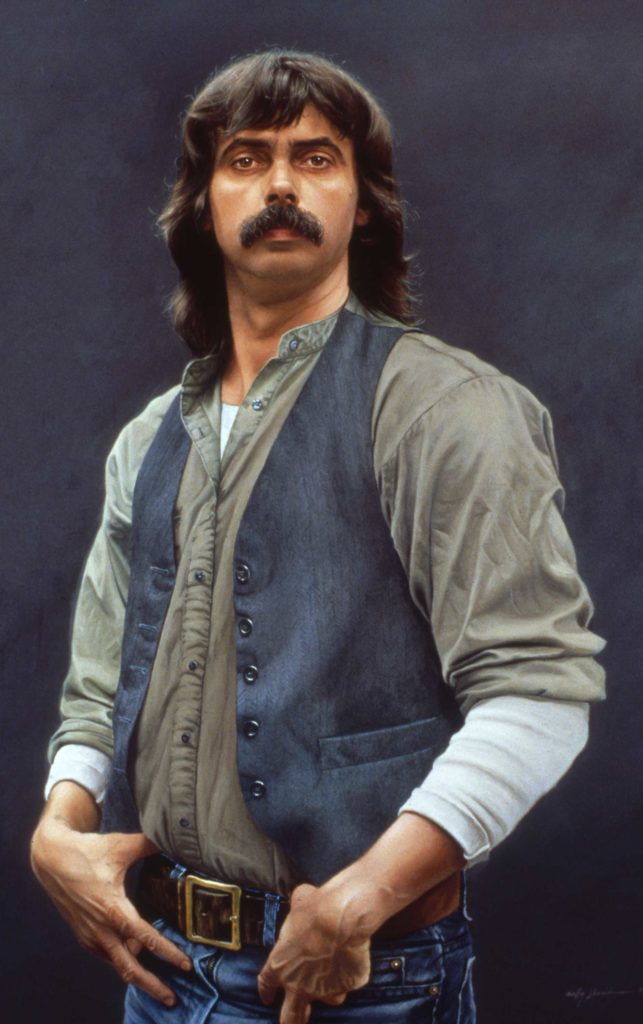

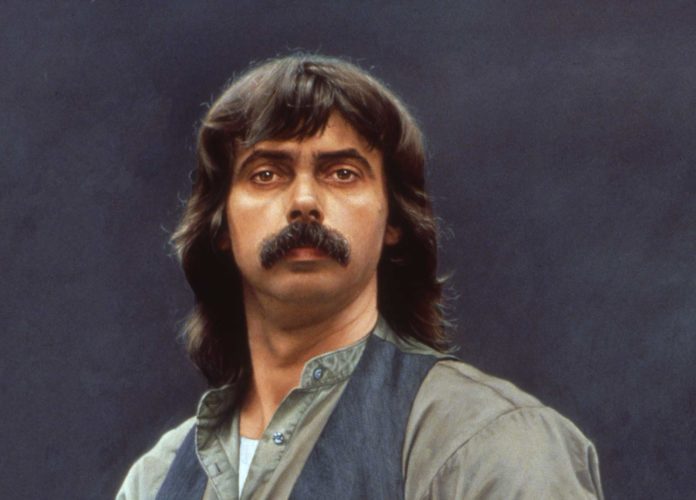

The artist concedes, “My paintings were not very good when Jeanne and I moved to the Falklands in 1976.” In response to an appeal from regions where Bahá’í communities needed assistance, the couple headed to these windswept islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, now best remembered as the site of a brief but furious war in 1982 between their owner, Great Britain, and neighboring Argentina.

The low cost of living there allowed the couple to survive on Jeanne’s salary, so Duffy took up painting full-time, experimenting with different styles and consulting the photos of artistic masterworks — both historical and contemporary — mailed to him by American friends. “The isolation and religion we experienced in the Falklands were critical to my art,” he recalls. “I had time to formulate my style and follow my heart in its expression, and I learned to love to look at stuff.”

Among the objects of his attention were native Falklanders — generally a quiet, introspective population of shepherds, lighthouse keepers, and the like. By the time war broke out six years after his arrival, Sheridan had created a group of locals’ portraits that would soon be exhibited to great acclaim in London, where curiosity about this distant part of the British Empire was keen.

Having ignored calls to evacuate, the Sheridans looked after other residents and spent 56 consecutive nights sleeping head-to-toe in the crowded bunker of their babysitter’s family. After painting 11 scenes from the Falklands’ history for a set of Royal Mail postage stamps, Sheridan departed in 1983 with his family. Most of the art he had made there was destroyed, not by bombs, but by Duffy’s own hand — he felt it was just not good enough to bring to his life’s next chapter. Fortunately, his unflinching self-portrait from this period (illustrated here) made the cut.

The Sheridans spent three years in a remote part of Northern California, and in 1986 they headed to American Samoa, in the South Pacific. During five years there, Duffy painted a portrait of Samoa’s head of state (another member of the Bahá’í Faith), as well as a huge scene for the island’s Roman Catholic cathedral.

Yet another chapter opened as the family moved to Arizona, first to artistic Sedona, and then — in 1997 — to help create Desert Rose Bahá’í Institute, a center for the arts and agriculture at Eloy, halfway between Phoenix and Tucson. This rural enclave has truly become home, to the extent that the Sheridans are helping to launch an artist residency initiative there; their goal is to reinvigorate the participants’ “sense of what it means to be an artist today, to benefit from this atmosphere of uninhibited artistic expression, and to share all of that with the community.”

In the meantime, Duffy keeps busy painting, Jeanne making ceramics, and their neighbors developing permaculture practices at Desert Rose.

TOKENS OF THE DIVINE

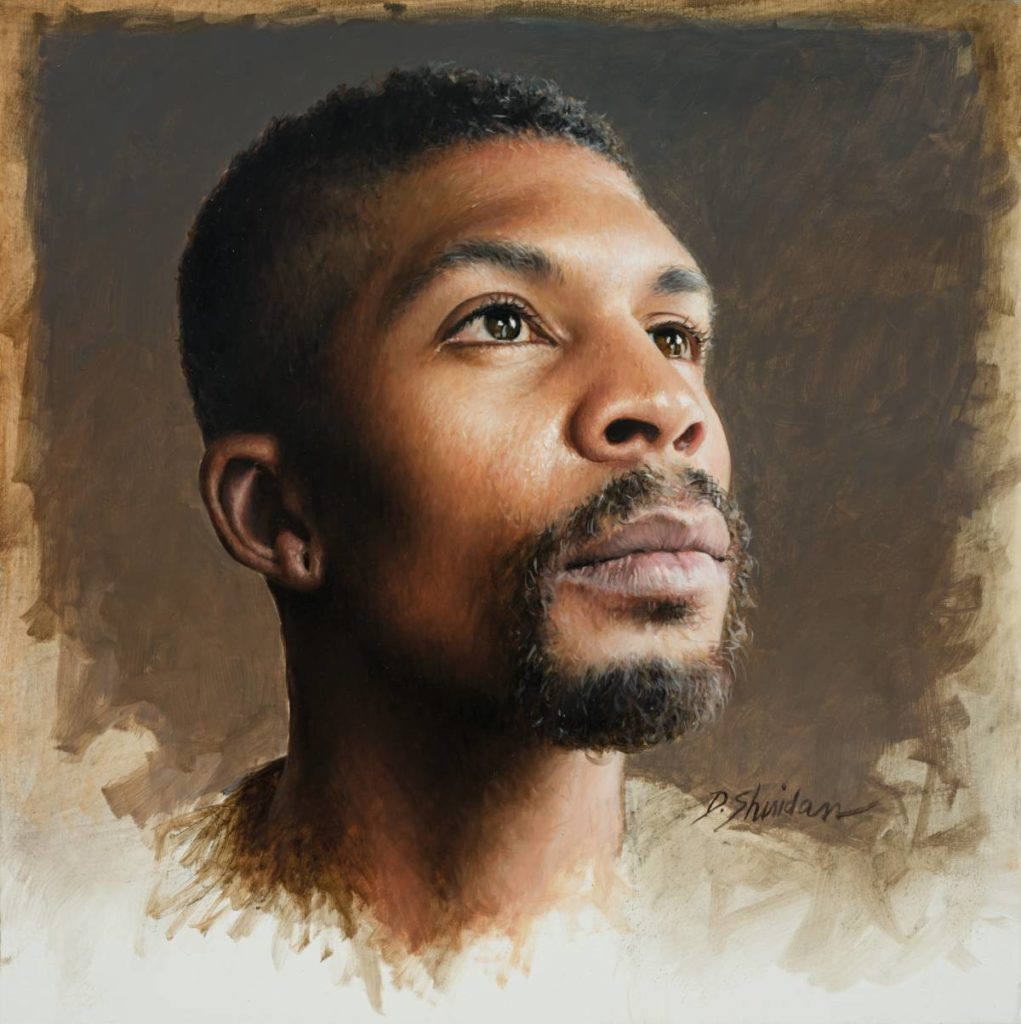

Sheridan explains, “It is not my aim to make great philosophical statements with my paintings, but instead to explore, and allow my audience to explore, those simple elements of human expression that reveal tokens of the Divine. My eye — my heart — is always attracted to things which are beautiful. People want to be uplifted, and so I try to bring hope through beauty to a despondent humanity.”

The results of this effort are Sheridan’s straightforward likenesses of young people, especially women, notable for their deft blend of exacting detail and an inner life that transcends mere photorealism. Seeking what he finds “emotionally attractive” in the sitter, the artist seemingly delves deep into each model’s soul, bringing viewers into communion with her or him.

Each of these oil portrait paintings takes at least one month to complete, working from the live model or photographic references Sheridan takes himself. He works in a windowless studio under artificial lighting that matches the gallery lighting where the finished painting will be exhibited. Sheridan also makes luminous images of women posed in woodlands or by the sea, and every five years or so he makes another self-portrait to mark his own development.

“If I had to do it again,” Sheridan reflects, “I would be a sculptor, but I have not lived in places where I could have done anything with the results. Paintings are easier to handle and transport.”

In fact, his portrait paintings evoke sculpture in their immediacy and palpability; we suspect that some of them might get up and walk off the canvas any minute. Sheridan rightly feels that his work is only getting better over time, and he realizes how fortunate he is to have only ever painted what he wants — to never have felt pressured to make one specific thing again and again.

Connect with Duffy Sheridan and see more of his portrait paintings: duffysheridan.com

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, how to create realistic portrait paintings, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue

By far the best of the best in our day and age.

Krystal Allen