On an art authentication foundation that helps root out fakes and frauds — a growing problem in the 1960s.

by Leslie Gilbert Elman

The International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) was established in 1969 at the suggestion of New York state’s attorney general to fill the void for an “authoritative, impartial, not-for-profit body to research works of art with uncertain authorship and also educate the public about art world issues.” For individual collectors, IFAR would help determine whether an heirloom that someone’s great-grandfather considered a Rubens was indeed that master’s work. For institutions, it could help to root out fakes and frauds — a growing problem in the 1960s.

Around this time, for instance, art forger David Stein was making and selling false Picassos, Modiglianis, Klees, and more at an alarming rate. He was arrested in New York in 1967, when Marc Chagall spotted a fake of his own work, painted by Stein, hanging in an exhibition. Stein pled guilty to six counts of counterfeiting and grand larceny, served time in prison, went to France after his release, and was arrested and convicted there as well. Nevertheless, Stein’s paintings in the styles of modernist masters — this time signed with his own name — were shown in a 1970 gallery exhibition titled “Forgeries by Stein,” and he was even enlisted to make the fakes featured in director Alan Rudolph’s 1988 film, “The Moderns.”

To be sure, stories of exploits such as Stein’s are tantalizing, and it’s understandable when they become the subject of articles, books, and even films. Yet, sadly, cases of misattribution, fakery, and fraud happen more often than art world professionals might care to admit. They inflict serious damage and have long-lasting ramifications. In 1969 there was an undeniable public need for IFAR, an independent, objective source that could conduct unbiased research to determine an artwork’s authenticity.

Over time, IFAR’s mission broadened to include investigations into provenance, particularly related to the restitution of artworks looted by the Nazis in the 1930s and ’40s. It created and maintained the Art Theft Database (precursor to today’s Art Loss Register) and has provided expert guidance and scholarship to Interpol, the FBI, and other law enforcement agencies.

This is the work for which IFAR is best known. But over the course of its 50 years, IFAR’s resource offerings have expanded to include a comprehensive Catalogues Raisonnés Database with more than 4,500 entries for over 3,000 artists — from Hans von Aachen (1552–1615) to Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664). IFAR also created the Art Law & Cultural Property Database of legislation and case law from the United States and abroad related to cultural property ownership and loss, authenticity, and restitution. This is an invaluable resource for attorneys, scholars, collectors, and anyone else interested in this continually expanding legal area.

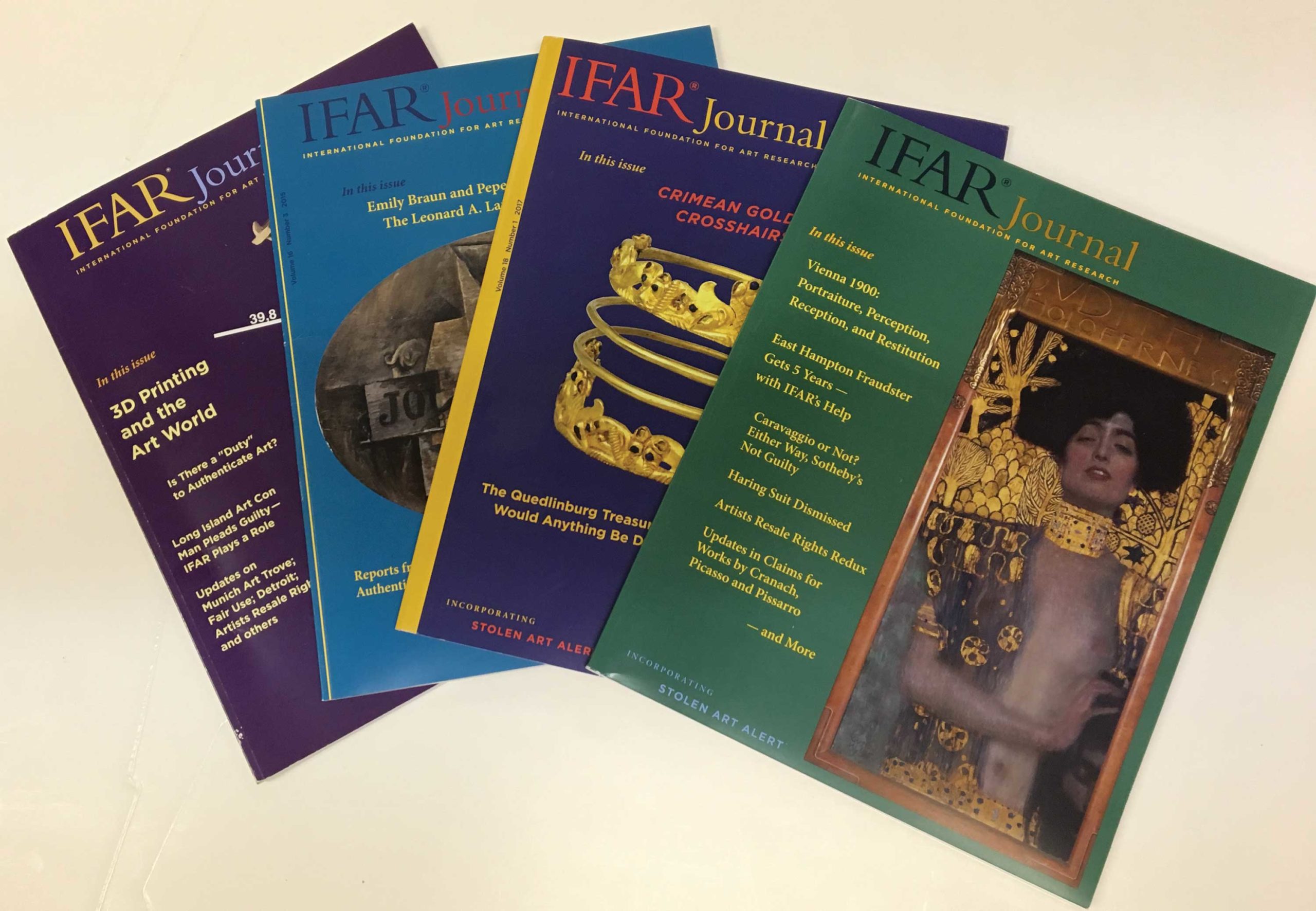

IFAR’s members include museum professionals, dealers, scholars, collectors, students, and “a lot of attorneys,” executive director Dr. Sharon Flescher says with a smile. “They look to us for our research services, online resources, the quarterly IFAR Journal, and our events.” In fact, the organization’s public programs addressing top-of-mind subjects are almost always sold out. (Just for example, “What Is It about Modigliani?” and “Notre Dame: Iconic Cathedral; Disastrous Fire; Uncertain Future” took place in 2018 and 2019, respectively.) Today all of IFAR’s work is funded by contributions and dues, subscription and submission fees, sponsorships, and grants. It is not an endowed foundation.

“We guard our reputation for integrity jealously,” Flescher notes, adding that any owner of an artwork who engages IFAR’s Authentication Research Service must sign an agreement stating that she or he understands that IFAR’s determination about its authorship may not necessarily be what the owner was expecting or hoping for. “We have no vested interest in the outcome of the research,” she explains. “We don’t buy, sell, or even appraise art for monetary value.”

It Might Be a Mount, But Not William Sidney

On rare occasions, the results of IFAR’s research may raise unexpected questions without answers. Such was the case when it was asked to say whether a painting known as “Sportsman at the Well” was the work of American genre painter William Sidney Mount (1807–1868). It was nearly identical to “At the Well,” an 1848 painting known to be by Mount and now in the collection of Connecticut’s New Britain Museum of American Art.

An example of the idealized rustic scenes for which Mount is known, the painting in question was also signed and dated 1848. The fact that it had been owned by Mount’s descendants as recently as 1941 would indicate it was not a forgery, and Mount was generally known to have painted several versions of the same scenes. Nevertheless, the quality of handling and treatment of details in this example were inferior to what we see in Mount’s known works — a fact made clear when it was placed side by side with New Britain’s version.

So, if Mount didn’t paint “Sportsman at the Well,” who did?

IFAR’s investigation turned up a couple of candidates, most likely of which was Mount’s niece, Evelina. Like her uncle William and her father Henry, Evelina Mount was a skilled artist. She frequently copied William’s work and he advised her on techniques and materials. They lived in the same house on Long Island for several years, and Evelina took over his studio after his death. Similarities between Evelina’s work and William’s — right down to the materials they used — are thus easily explained. Yet because no evidence was found to confirm Evelina’s copying of this specific painting, her hand in its creation can still only be assumed.

Art Authentication: Of Rembrandts and Restitution

Of the many cases in which IFAR has been asked to provide expertise, one that began in 2002 and took more than two years to complete stands out for Flescher because of its rare resolution.

It began with an American professor who inherited a Rembrandt drawing she had reason to believe had once belonged to Arthur Feldmann, a lawyer in Brno, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). On March 15, 1939, the day the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, Feldmann’s collection of some 700 Old Master drawings was confiscated by the Gestapo. He and his wife died at the hands of the Nazis, and their art collection was eventually dispersed. Much of it remains unaccounted for. Some works were sold at auction by Sotheby’s London in 1946; four works made their way into the collection of the British Museum.

In 2002, after reading that Feldmann’s heirs were searching for objects from his looted collection, the professor (who prefers to remain anonymous) sought to confirm the provenance of her drawing. If it had indeed been looted, she wanted to return it to Feldmann’s family without recompense. She consulted a museum director on how to proceed with confirming the provenance and finding Feldmann’s family. The director referred her to IFAR.

As Sharon Flescher recalls, putting the professor in touch with Feldmann’s family, although initially difficult, turned out to be fortuitously simple: his grandson, Uri Peled, who had initiated the search, was a new subscriber to the IFAR Journal. The connection was facilitated and the research began.

Records reviewed by IFAR and the Commission for Looted Art in Europe (CLAE), which was representing the Feldmann family, showed that the drawing — “The Liberation of St. Peter from Prison” — had appeared at the Sotheby’s sale in 1946. The professor knew that her family acquired the drawing in good faith from an Amsterdam dealer in the 1970s. Now it seemed clear that the drawing was part of the looted collection and would be returned to the Feldmann family, but there was a surprise in store.

“Although our task was to determine whether the work had been looted, we also examined the drawing itself,” Flescher recalls. The late Egbert Havercamp-Begemann, a professor at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, member of the Rembrandt Research Project in Amsterdam, and longtime member of IFAR’s Art Advisory Council, lent his expertise. “It was his opinion that the drawing was not by Rembrandt, but by a follower, probably Govert Flinck,” Flescher says. That had also been the opinion of another great Rembrandt scholar as far back as 1956. In 2004 the drawing was returned to the family, who two years later presented it to the British Museum, where curator Martin Royalton-Kisch affirmed the work was by Flinck.

This reattribution might have made the drawing less “important,” but its significance in cultural history remains undiminished: this case marked a rare instance that a Nazi-looted artwork was returned to its rightful owners unprompted and without compensation of any kind. “The professor was, in my mind, a true heroine, as no one would have known she had the drawing,” Flescher notes. “From the start, it was her intention to err on the side of generosity.”

It’s safe to say that every IFAR investigation, even if it ends with a question mark, adds something to art-historical scholarship. Each study is exhaustive and may require many months to complete, yet it is work that needs doing. “We have dealt with issues of theft, looting, fakes, and so on, for 50 years, long before they became ‘sexy,’” Flescher explains. “Now they are more in the news than ever, making our work more significant than ever. But I think our supporters fund us because they realize how important — and sorely needed — integrity in the visual arts is.”

For more information: www.ifar.org

View artist and collector profiles here at FineArtConnoisseur.com.

I was not aware of IFAR and found the story interesting. Being a painter and at times a collector and a frequent visitor to art museums I have often questioned the authenticity of some paintings I have viewed. However not having the expertise I am ungualified to judge a work of art by an old master etc. Some of the works I see are obviously not by the named artist’s hand, brush strokes paint thickness etc, however I leave wondering just how many works exhibited are in fact fakes. I often find that some employees of Musuems and galleries do not have a real passion for art and look upon their position as a Job as a means to pay their bills. The Art world is a business that unfortunately attracts unscrupulous people out to make a quick profit. I understand that upwards of twenty plus people (non artists) make a living from the labours of full time artists?

What happens when IFAR gets it wrong, they talk about how they do all this research but will they admit it if they find out later that they missed important information and caused a Masterpiece not to be authenticated when it should have been?