From the Fine Art Connoisseur July/August 2023 Editor’s Note:

Embracing the Future, Carefully

Every day I seem to be reading another story about Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its potential benefits and drawbacks. Despite stern warnings from the very people who pioneered this new technology, our society is moving full steam ahead, introducing programs like ChatGPT to the public at breakneck speed. Though I lean a little Luddite, I am not automatically opposed to the idea that a chatbot might save us time and brainspace by performing tasks we normally dread. The Internet itself, initially developed for military purposes, has proved a boon to humanity (with the downsides inherent to any technology), so why not AI?

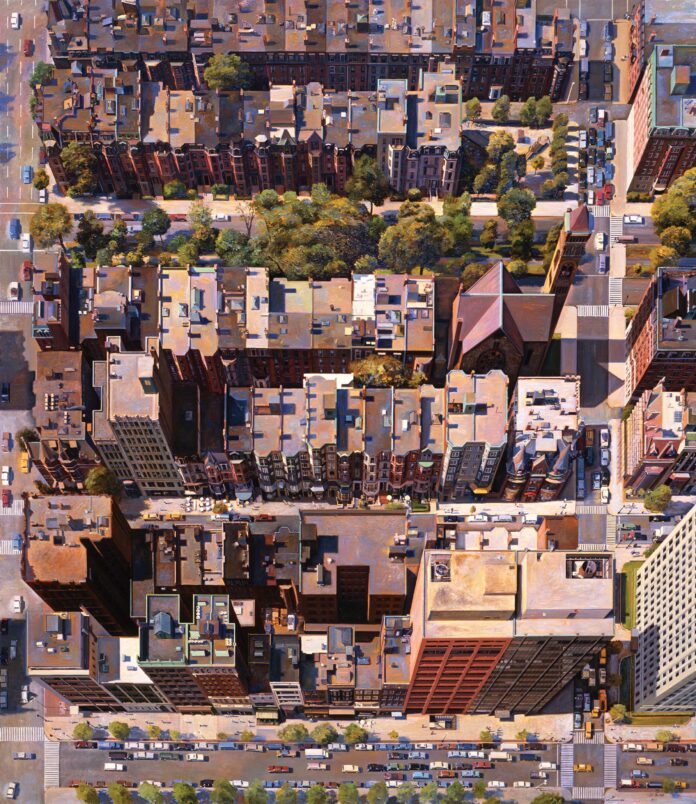

Setting aside the proliferation of — just for example — “deep fake” AI videos designed to mislead viewers, my chief worry for the field of fine art is one that has already existed there: deceptiveness. Years ago I noticed, at an art fair, that visitors were excitedly admiring an enormous oil painting with wonderfully expressive brushwork.

Upon closer inspection, I realized this was actually a photograph onto which the “artist” had applied masses of paint to make that underlying fact less obvious. Problem is, the dealer’s wall label did not mention anything about photography — it was simply an “oil on panel.”

I don’t know whether the painting sold, but the experience immediately reminded me of the phrase “buyer beware,” and that trickery has always been around. Indeed, one reason we publish Fine Art Connoisseur is to show readers the best art so that they can keep refining their aesthetic “eye”; I doubt our longtime readers would have taken the bait at that fair. They would have sensed something was amiss, that it was not an entirely handmade painting.

I relate this tale from the past because now we can fully expect AI technicians to start moving digitally created “artworks” onto the fine art market. Some distributors will acknowledge this heritage right up front, but less scrupulous ones may pretend the art is handmade. This is, obviously, a direct threat to the real-life artists who devote way more time than any software does to creating a genuine work of fine art.

But — and this is crucial — such deceptiveness will only be a threat to artists if potential buyers cannot tell the difference and do not ask sellers how these artworks came to exist. One of the many things I love about looking at art is learning the story of the person who made it. I know I will be amused the first time I encounter an AI-created work (properly labeled!) and learn from its seller about the software that was used; surely I will feel a touch of wonder, but then — within minutes — the boredom will set in.

That software (or app, or program) does not have a human being’s backstory: it did not grow up drawing on the living room walls, it did not drop out of art school, it did not suffer a trauma and then discover it could paint the pain away. “This artwork was made by AI” will be where the dealer’s pitch starts and ends. Boring.

So here is the challenge I assign you today, dear reader. When you are moving through a gallery or fair or festival, do not hesitate to ask the seller about the artist who made the work you admire. First, it will be genuinely interesting to learn who that person is. Second, you will implicitly be putting the seller on notice that you are really looking and listening. Third, sellers will be entering fresh legal territory if they lie to you about who or what made the art. (Please see Daniel Grant’s comprehensive article on page 107 in our July/August issue about the legal rights a buyer has when the seller has been misleading.) The more sellers have to talk, the more power you as the viewer-customer accrue, and the more uncomfortable the unethical sellers will become.

My prediction, then? AI-generated artworks will sell best online, where the buyer sees only the flat, digitized image and cannot inspect the surface closely. That’s also the setting where sellers don’t have to say much — the encounter is transactional, and that’s just the way unethical sellers want it.

I do not mean, for a minute, that we should not be buying art online; if it’s a reputable dealer or artist offering works online, go for it, just as you already have. But, let your “buyer beware” kick in when unfamiliar names and images start appearing on your screen. Ask questions and look not only with your eyes, but also with your ears.

What are your thoughts? Share your letter to the Editor below in the comments.

Download the current issue of Fine Art Connoisseur here.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the free weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

I agree Peter. I like to know that paintings are made by a human hand. There is nothing that can replace the individuality which a human brain and hand can create.

I think some of the problem is that artists using drawing apps or the like somehow make themselves believe it’s OK, since some artists from the past used a camera lucida or such. It’s symptomatic of the emphasis on technique as being the main aspect of art. They ignore the process of letting the visual stimulus go through the eyes into the brain and be triggered by a creative force that gives a voice to the visual creation by coming back out through the hand with the eye guiding to make a creative statement. Tracing an image is not a creative statement, even though I admit that traced images could be used to create an artistic composition/creation.