A look at the dramatic shift of David Park (1911–1960), an abstract painter who later became one of the founders and most prolific practitioners of the Bay Area Figurative Art Movement.

Figuring it Out

By David Masello

The two Bay Area softball-league teams took to the field for another game. The team known as the Figs (composed of figurative painters) appeared to be the aesthetic underdogs against the Creepy Crawlers (abstract expressionists) — especially during seasons from the mid-1940s to the early 1950s. That’s when the loudest roars from the bleachers favored abstraction, the preferred style. While the scores of those games are not recorded for posterity, the debate continues as to which team won.

When the painter David Park (1911–1960) took to the field for the Figs, while he was teaching at San Francisco’s California School of Fine Arts from 1944 to 1952, he could actually have played on both teams. Park, who soon became one of the founders and most prolific practitioners of the Bay Area Figurative Art Movement, had previously painted abstract works, almost all of which he destroyed. (Legend has it that, around 1950, he either burned the canvases or tossed them into a dump.) Though he embraced figuration, he produced art that still flirted with abstraction.

This dramatic shift, which lasted until his death at the age of 49, was celebrated and revealed to its fullest glory in “David Park: A Retrospective,” a show of 125 works mounted by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA).

A UNIQUE PATH

“David Park charted his own path at a moment when painting from the figure was anything but the cool thing to do,” says Janet Bishop, SFMoMA’s chief curator and curator of painting and sculpture, who conceived and realized this project. “He painted in the abstract view in the postwar period, when the most interesting avant-garde painters on both coasts were doing the same. But it never felt authentic to him. When he stopped doing those works, he went on to make some of the most powerful figurative canvases of the 20th century.”

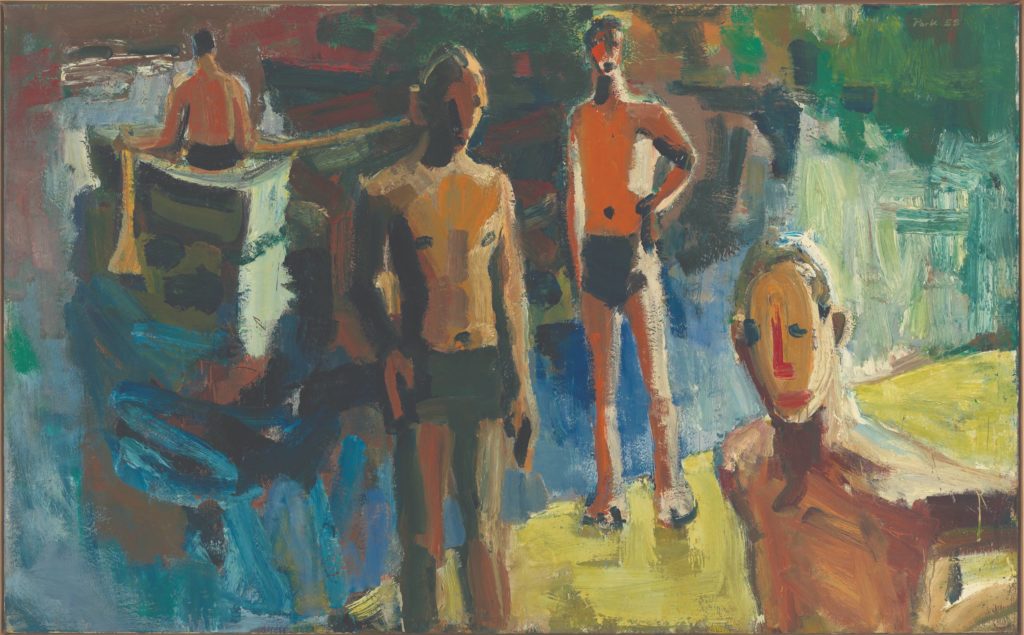

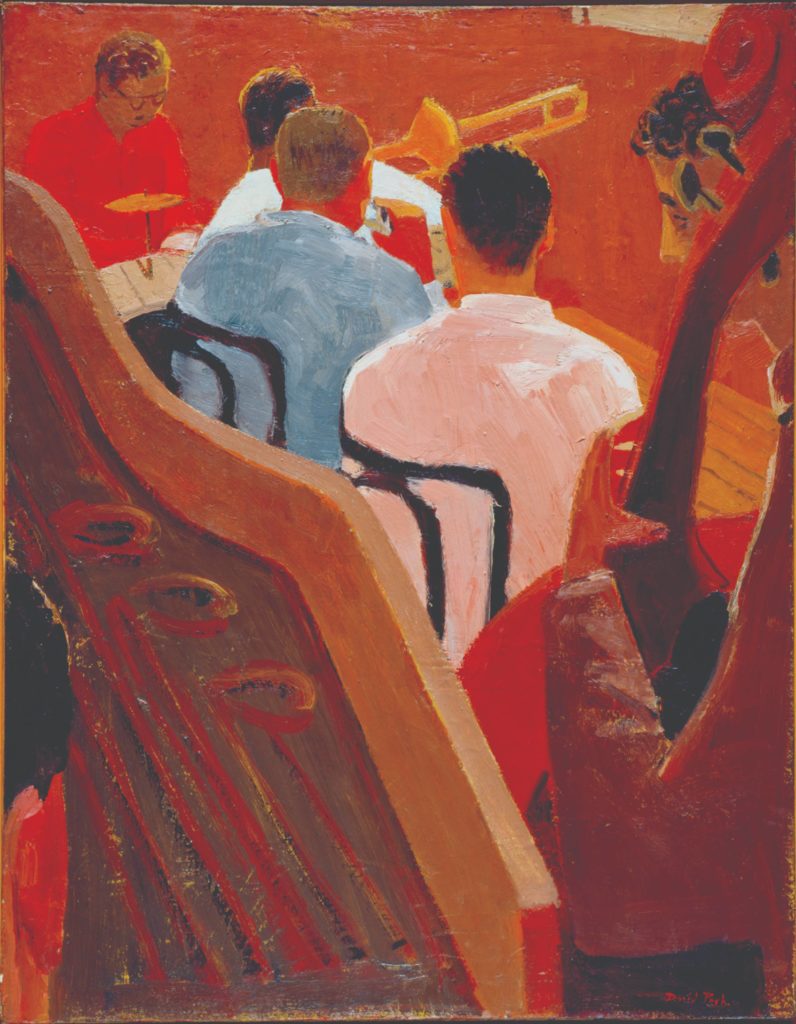

By embracing the human form, especially in motion — nudes wading in a river, jazz musicians blowing horns and fingering saxophones, a balloon seller working a city street — Park proved, ironically, to be the radical artist of his time, not his contemporaries, who included the likes of Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still.

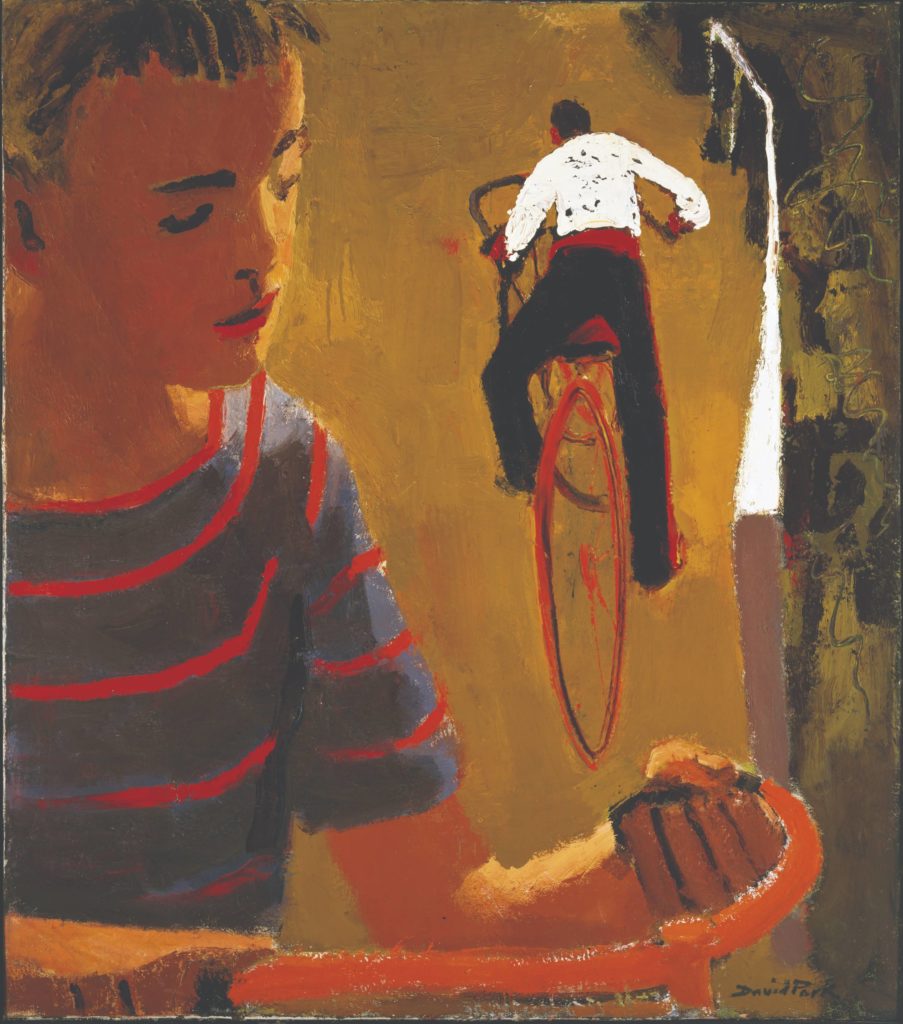

In fact, Park’s friend Richard Diebenkorn, upon seeing one of those early figurative works, “Kids on Bikes” (1950), said, “My God, what’s happened to David?” — as though only a misguided artist would render a discernible depiction of figures at play and think it appropriate. (In time, Diebenkorn, who remained close with Park, would also embrace a more realistic approach. He became a leading member of the so-called Bay Area Figurative Painters, along with Park, Elmer Bischoff, and Paul Wonner.)

And yet Park appears never to have been dogmatic about his shift. During a 1952 interview, quoted in Bishop’s catalogue essay, he said, “I believe that the best painting America has produced is in the current non-objective direction,” a more polite term for abstraction.

As to why he chose to depart from the movement that then ruled the galleries and art schools, Park added, “…I often miss the sting that I believe a more descriptive reference to some fixed subject can make.” While he acknowledged that some non-objective canvases can be “visually beautiful,” he also found them “insufficiently troublesome, not personal enough.” Though objections to his figuration were often personal in nature, he was diplomatic and generous enough to recognize the merits of both approaches. He could play on both teams in those softball games, though his preferred uniform was that of the Figs.

Sara Wessen Chang, SFMOMA’s curatorial assistant of painting and sculpture, was responsible for organizing the museum’s accompanying show, “David Park and His Circle: The Drawing Sessions.” She also emphasized the “radical” nature of what Park produced when he was producing it: “At the California School of Fine Arts, he felt very uncomfortable and forced to work in the abstract manner,” says Chang. “He was the first one in his group to turn his back on the movement, and to make a bold move to paint what he wanted.”

While it may be facile to say that those who prefer figurative art are, by nature, more people-oriented, remarks by Park certainly suggest he was involved with, and keenly observant of, day-to-day life. In 1952, he emphasized his desire “to paint subjects that I know and care about… in commonly seen attitudes. It is exciting to me to try to get some of the subject’s qualities, whether warmth, vitality, harshness, tenderness, solemnness, or gaiety, into a picture.”

Park’s wife, Lydia, whom he married in 1930, remained a constant champion of his work and methodology, even when he impetuously quit his post in 1952 at the California School of Fine Arts (now called the San Francisco Art Institute) after a new director promulgated abstraction only. By that point, Park and his wife had two young daughters, Helen (who in 2015 published “David Park, Painter: Nothing Held Back”), and Natalie.

It would be misleading to say Park enjoyed no success with his figurative scenes. When “Kids on Bikes” (1950) won an award at the San Francisco Art Association Annuals, Lydia wrote to her sister-in-law, “It was a scream to see all the old kind of stuff, the non-objective, etc., with all the old ‘modern’ look about them in the gallery and to see this with a prize label on it.”

Bishop recounted how Park’s peers derided him for “chickening out” or suffering from a “failure of nerve” in his desire to paint what is discernible, real, all around us. Yet, even though the subject of “Kids on Bikes” is immediately graspable, the perspective from which Park chose to depict the boys is far from predictable. One boy looming in the immediate foreground is backdropped by another pedaling away on a bicycle with oddly large wheels; we see this retreating figure from an aerial perspective. Ghostly suggestions of other figures appear behind a white fence. Somehow the painting manages to be colorful, poetic, animated, and narrative in quality while the main figure appears contemplative as he grasps his curvaceous orange handlebars.

MAKING HIS OWN WAY

Park was born in Boston. Even though his family was learned and worldly, composed of teachers and ministers, he received little encouragement to become a painter, except from an aunt who lived in Los Angeles. At 17, he moved west to live with her while attending that city’s Otis Art Institute. Upon graduating, at the height of the Depression, Park began painting murals through the Works Progress Administration (WPA). His future wife was the sister of Gordon Newell, a sculptor with whom he shared a studio in Los Angeles.

By 1936, Park, his wife, and their daughters returned to Boston. The late Paul Mills, who headed the Oakland Museum’s art department in the 1950s, and who was responsible for conceiving the 1957 exhibition of the Bay Area New Figurative painters (the first of its kind), wrote that by 1941, Park had “moved from the figure styles of WPA art into the startling adventures of Cubism and other modernisms.”

Park and his family moved to the Bay Area, where he began teaching and indulging in what he tried to convince himself was his métier: abstraction. “By 1949 or 1950 he decided that the work he had been doing in this style was invalid, and he took almost all of his abstract canvases to the Berkeley dump and destroyed them,” Mills wrote.

Throughout the 1950s, as Park’s figurative art gained a following — praise eventually outweighing derision — he secured teaching jobs, commissions, and, ultimately, a solo show at New York City’s Staempfli Gallery in 1959. According to Chang, Park took a year’s sabbatical from teaching to create more paintings for that show, a fortunate development given that some of his strongest works resulted during this period.

These included “Four Men” (1958), one of whom might be a self-portrait; in this respect it was not the first of its kind, as the rakishly handsome artist is thought to have depicted himself in other works, such as the frankly depicted figure in “Standing Male Nude in Shower” of 1955. (Chang notes that Four Men has been rarely exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art since a 1988 Park show there.)

Of this highly productive period leading up to the 1959 show, Bishop says, “Park was painting with an incredible command of his materials. And there’s almost a teetering between recklessness and control. What resulted are potent, psychologically charged, energetic canvases.” Though Park had typically painted in oils on canvas, he was shifting toward watercolors and gouache on paper.

On Painting Figurative Art: “He Loved People”

Many of Park’s figures from the late 1950s loom extra-large, close up on the canvas, their faces filling the ground, their gestures and expressions unignorable. His nude men and women are both painterly and alluring. “He loved to paint and he loved people,” says Bishop. “He enjoyed drawing from both the female and male figure. He really was a humanist. And in his series of bathers, you don’t see a preference for either clothed or unclothed figures.” Chang adds, “He focused on moments of human experience, moments between people.”

By 1959, Park was afflicted with debilitating chronic back pain and, as it turned out, cancer, which would claim him a year later. During Park’s initial illness, Diebenkorn and other friends built for him a special desk at which he could paint on the ground floor of his Berkeley home. (He had recently been teaching at the University of California, Berkeley.)

Lydia bought him all eight colors of what was then a brand-new medium, felt-tip pens. She also purchased a 30-foot-long roll of shelf paper. Every day, in his customized workspace, Park would unspool more of the scroll and produce another drawing, one melding with another, yet each its own distinct scene. Many referenced his boyhood, notably animated scenes from Boston Common — Sunday picnickers, rowboaters, sailors on leave, and nearby streetscapes.

Mills likened the scroll to “a marvelous, spontaneous jazz improvisation,” adding that “the style, the handling of the different subjects, the gradual or abrupt shifts of scene, everything about it suggests something that just happened as Park moved along.”

Many scholars regard the scroll as a kind of visual autobiography, though Park departed from the chronology of actual events. Bishop emphasizes that the artist drew himself into many of its scenes. Because of his infirmity, Park apparently never saw the entire completed work, unspooled end to end; he would simply roll up the finished work after it dried and begin a new one on a blank surface. Due to the fragility of the scroll and the risk of further fading (early felt-tip ink is notoriously fugitive), portions of the scroll were shown only at SFMoMA, while digital images of the full work were shown earlier in the national tour.

Almost too ironically, the scroll’s final panel depicts a balloon seller, behind whom looms a street sign announcing “Dead End,” accented with a skull-and-bones. Mills noted that, by this point, Park’s illness had still not been diagnosed as final, though he seems to have grasped his fate. Referencing Park’s entire output, Mills concluded, “He created a remarkable series of figures and heads imbued with a profound seriousness and directness as they stare at us, wide-eyed.”

So self-aware and confident was Park that in 1957 he was quoted in the catalogue accompanying Mills’s show as saying, “As you grow older, it dawns on you that you are yourself — that your job is not to force yourself into a style, but to do what you want.”

Park’s art exemplifies the ongoing power of figuration. His people are expressive, yet elusive. We know where they are and what they are doing, but enough remains only suggested to keep the viewer questioning. Even with figures whose features are deliberately blurred or rudimentary, we somehow know their personalities and characters. Park painted from life, scenes of life. The people he saw, we now see.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter for collectors covering figurative art, still life, Western art, and much more

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue