By Micah Christensen, PhD

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine contributor

There is and always has been a pecking order among artists and collectors; a kind of unspoken understanding of the difference between bon gout and faible couture. For centuries a codified hierarchy ranked artists, establishing the critical and financial fortunes of an artwork. This hierarchy was upended with the advent of Modernism. But now, as increasing numbers of artists seek out traditional techniques in art and compete for prizes, the question of hierarchy may be worth visiting, if only to explore our own stubborn biases.

Perhaps the most famous codifier of art was the French architect and historian André Félibien (1619-1695):

He who produces perfect landscapes is above another who only produces fruit, flowers or seashells. He who paints living animals is more estimable than those who only represent dead things without movement, and as man is the most perfect work of God on the earth, it is also certain that he who becomes an imitator of God in representing human figures, is much more excellent than all the others . . . a painter who only does portraits still does not have the highest perfection of his art, and cannot expect the honor due to the most skilled. For that he must pass from representing a single figure to several together; history and myth must be depicted; great events must be represented as by historians, or like the poets, subjects that will please, and climbing still higher, he must have the skill to cover under the veil of myth the virtues of great men in allegories, and the mysteries they reveal.

Félibien did not invent this list or its order. He repeated what had been the status quo from at least the late fifteenth century. It was, after all, Michelangelo (1475-1564) who once reportedly said “Good painting is nothing else but a copy of the perfection of God and a reminder of His painting.”

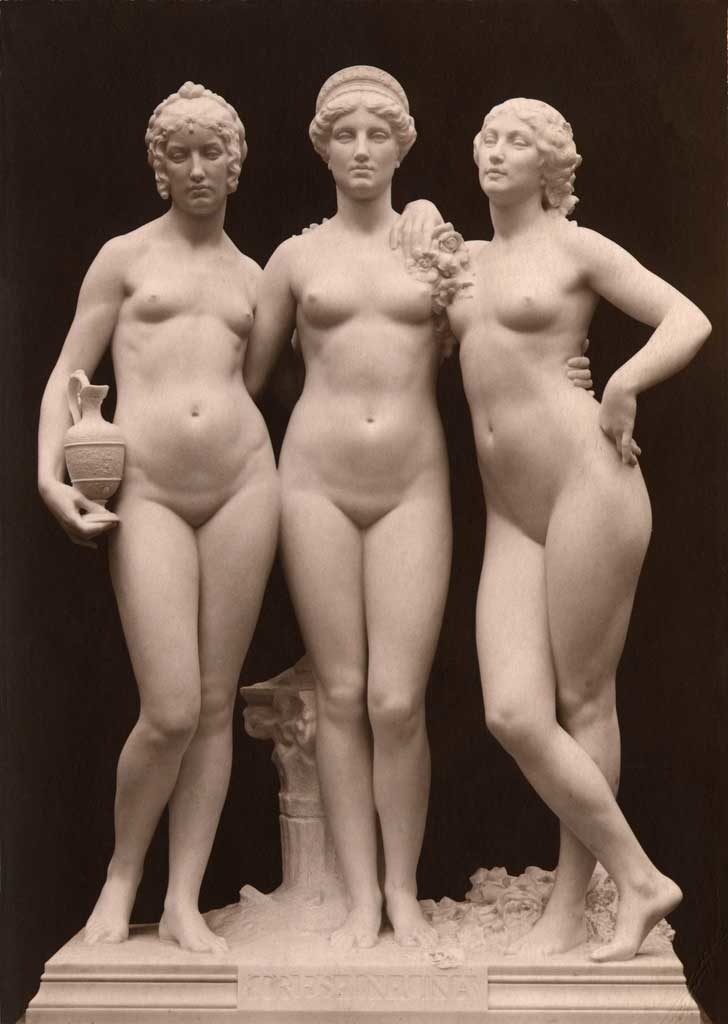

Today, making any such statements that would potentially rank one genre of art over another would not only seem politically incorrect, but also just incorrect. Is there any way of quantifiably comparing the arsenals of skills used by William-Adolphe Bouguereau (French, 1825-1905) to make a nude, with those of Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826-1900) — who would rank high on the genre chart — to create a monumental landscape such as “Niagara Falls.” Apples and oranges.

On one hand, the idea that narrative figural paintings occupied the highest order of art and landscapes near the lowest was simply an acknowledgement of what, today, we would call “socioeconomic differences.” From the Renaissance forward, art was increasingly the domain of gentlemen intellectuals, not the illiterate craftsman of Medieval guilds. These artists and collectors were often fluent in the classics of Greco-Roman literature. This was perhaps no better personified than by Peter Paul Rubens — called “the prince of painters” by the art-collecting King Charles II — who spoke at least eight languages and whose rich interpretations of mythological, biblical, and historical subjects reflect his depth of understanding won through relationships with theologians, kings, and philosophers.

But dedication to the human figure as a apex of arts education was also an acknowledgement that true mastery required a skill that was difficult to attain. Even the completely uninitiated art viewer can tell if a hand or an ear in a painting just doesn’t quite meet anatomical reality. How often have stories of Michelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci digging up and dissecting corpses been repeated? (I seriously doubt they did the digging themselves.) This kind of dedication often led science and art to meet in one individual, such as Paul Richer (French, 1849-1933), whose intimate knowledge of anatomy qualified him to serve simultaneously as a professor of the Paris École des Beaux-Arts and surgeon for the Académie National de Médecine.

But the figure was not the only subject that required rigorous understanding. The same Enlightenment that shed light on the human body led to increasing understanding of geology, climate, and nature. The result was generalist artists increasingly being replaced by specialists like George Stubbs (British, 1724-1806), who led dissections of horses at London’s Royal Academy, and the Hudson River School of landscape artists, who rigorously noted the elevation of plants and mineral composition of rocks. By the end of the nineteenth century, the curriculum of the various European academies broadened to teach these additional branches of knowledge.

We are not living in a time when there is increased interest in developing a similar rigor in art, as evidenced in the most recent Art Renewal Center (ARC) Salon. This year more than 3,700 artworks were submitted by artists from 69 counties. The ARC gave awards in nine categories, listed in the following order:

Figurative

Portraiture

Imaginative Realism

Landscape

Plein Air

Animals

Sculpture

Drawing

Still Life

This list, I think, with the exceptions of “imaginative realism” and “plein air” — two concepts that didn’t exist at the time — would have been remarkably familiar to the seventeenth-century André Félibien. Perhaps he would have wondered at the climbing of “landscape” above “animals.”

This list and its order should make any artist or collector pause. Yes, it is wonderful that efforts like the contemporary Hudson River Brotherhood, Florence Academy of Art (Florence), and the Grand Central Academy (New York), Academy of Classical Design (North Carolina) and Masters Academy of Art (Utah) — to name only a handful — are resurrecting a lost intellectual and technical approach to art. But are we also resurrecting old biases?

I recently put this to a crowd of artists, with whom I regularly gather for the Artistic Arsenals lectures. We had just had a discussion about a wonderful artist, Eric Armusik, who just completed a series of monumental canvases depicting scenes from the Divine Comedy (1320) by Dante Alighieri (Florence, c. 1265 – Ravenna, 1321). Armusik is deservedly considered a “Living Master” by the Art Renewal Center. But, after showing his works, I asked my audience: “Please raise your hand if you have ever read The Divine Comedy.” Out of dozens of people, not one hand went up. My heart sank, and I immediately felt a kinship with Allan Bloom, who described a similar result in his UCLA classroom in the book The Closing of the American Mind (1987).

Just as I was inwardly lamenting the death of bon gout, which surely showed on my face, the hand of Howard Lyon went up. Lyon has the distinction of having both won major awards as a fine figurative artist and being on of the world’s foremost fantasy artists. He asked:

“We may not have read Dante. But we have read Tolkien. Tolkien has not only been read by millions. Artwork — movies, paintings, and music — inspired by Tolkien have been experienced by perhaps billions. It is drawn from mythology and explores themes that are arguably as universal as The Divine Comedy, which was itself contemporary fiction. Why can’t we paint that and have it be considered ‘fine art’?”

I did not have an answer for him then. And, I don’t now; other than the acknowledgment that my biases, which lean toward the ancient and well-trod classics, are contradictory.

Years earlier, I had been in the London home of Peter Nahum, former Director of the Victorian Painting Department at Sotheby’s and the owner of the famed Leicester Galleries. He had been showing the work of Paul Raymond Gregory (British, b. 1949), an artist trained in the tradition of Harvey Dunn and NC Wyeth, who had spent 25 years creating monumental canvases inspired by the Lord of the Rings. Nahum considered Gregory’s works on par with those created by the nineteenth-century artists for whom he was considered an advocate. But Nahum had struggled to find an audience for Gregory’s works in the traditional museum and gallery world. His solution? ComiCon.

It is my impression that very few fine art sales are made at such conventions. Perhaps this is because my fellow fine art connoisseurs and I do not attend them in great numbers. But, rather than pass that off as a given, I would like to suggest something else: We should examine our own personal hierarchies of art (Tolkien versus Ovid, landscape versus figure, illustration versus fine art). And, perhaps, we should move towards a new hierarchy — one that both cherishes the greatness of the past and opens us up to new possibilities.

About the author: Dr. Micah Christensen received his PhD in the History of Art from University College London and his Masters in Fine Art from Sotheby’s Institute (London). For his research. Dr. Christensen, has worked with various institutions, including the Prado Museum, National Gallery, and Musée d’Orsay and Getty Institute. He is currently a partner at Anthony’s Fine Art (www.anthonysfineart.com). Dr. Christensen regularly holds discussions with contemporary artists on Old Masters and art theory, which are recorded and posted on his website: ArtisticArsenals.com.

Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, the weekly e-newsletter from

Fine Art Connoisseur magazine.

I suspect Tolkien would have been mortified if people put his book on the same level as “The Divine Comedy.” And I mean that, he, being catholic medievalist, would never have considered LOTR to have the same spiritual value as the latter and would have been just dismayed at the intellectual laxity of modern society, as you and I, dear writer.