Using Renaissance and Baroque traditions as a catalyst for her dramatic narrative art, painter Virginia Derryberry invites the viewer into her creative world — one filled with dichotomy, costume, mystery, and more.

Executed properly, narrative painting has near-infinite ways to transport the viewer through places, ideas, and experiences. There can be little doubt that painter Virginia Derryberry has mastered this process, establishing herself among the pantheon of Asheville, North Carolina, artists.

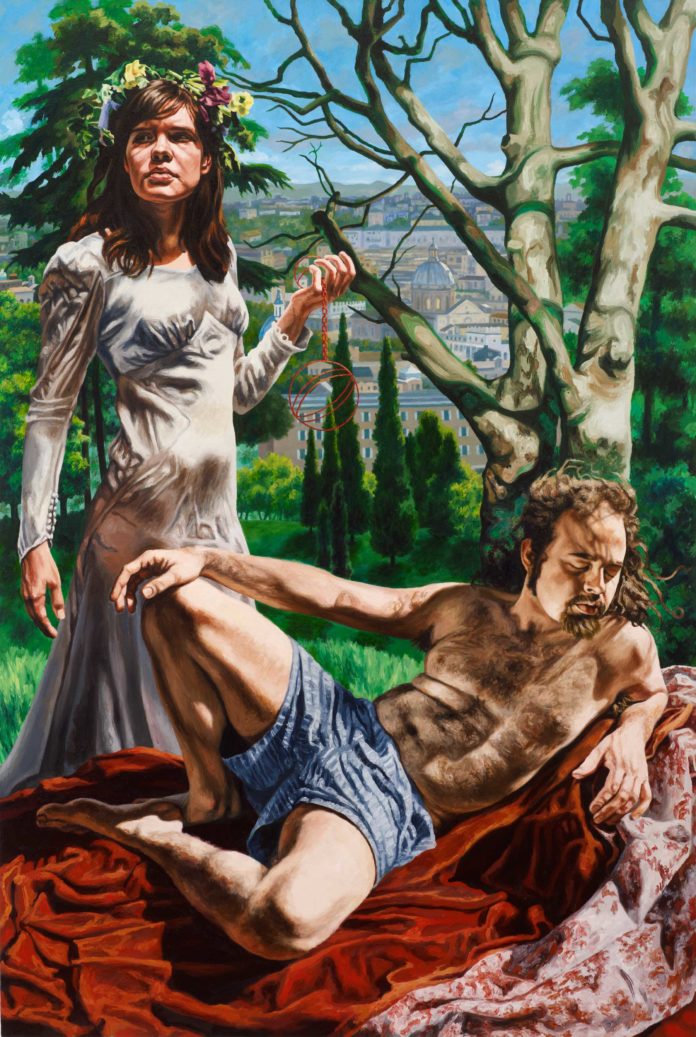

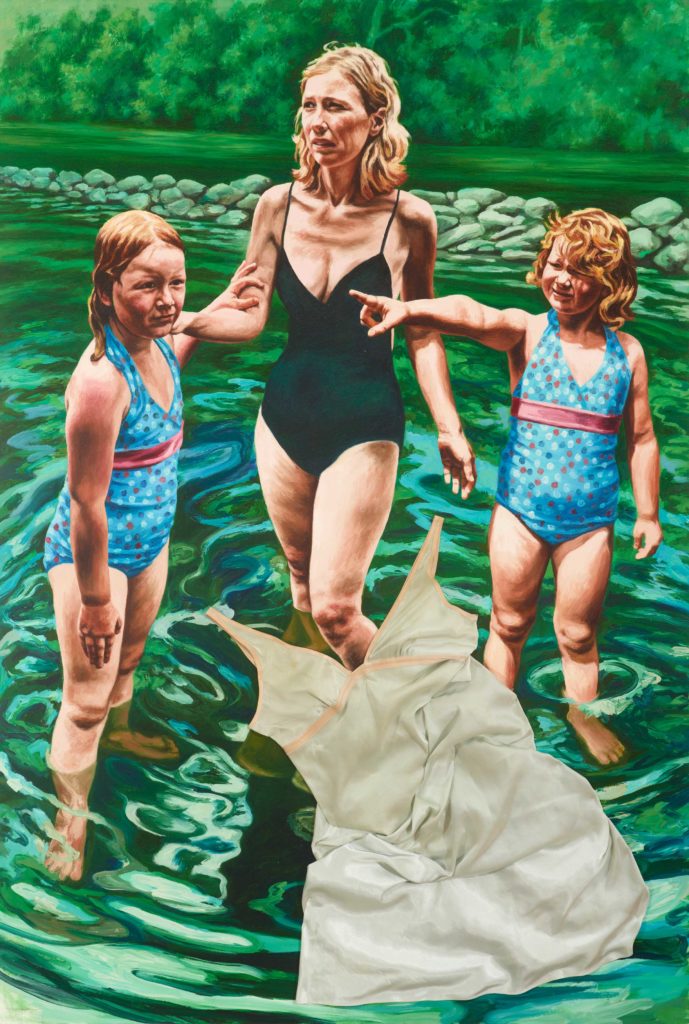

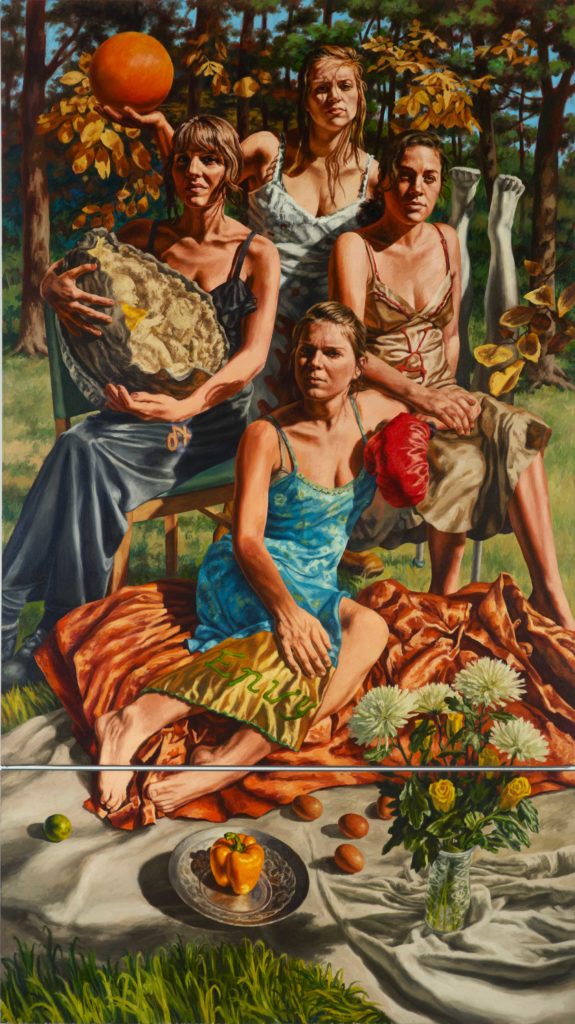

Derryberry’s story has many points of entry, but experiences as a young student at Vanderbilt University proved pivotal for her artistic career. An art history major who occasionally experimented in art-making, Derryberry found herself greatly attracted to Renaissance and Baroque imagery, specifically pictures with strong lighting, complex compositions, and engaging narratives. “Many of these images stay with me,” she writes, “so when I begin the drawing/visual research for a new piece, some kind of related scenario pops up in my head. I use that image (or images) as a catalyst for environment, lighting, body language, and costuming for my models. Over time, I’ve really started to think of myself as being like a cinematographer, always visually ‘scanning’ a space or environment for possibilities. I usually work on ‘suites’ of pieces, sort of a small group of images within a larger series, so one piece often tells me what to do next — not exactly like the chapters in a narrative or scenes in a play — but related to the idea of time, performance, and character development.”

With this in mind, it should come as no surprise that Derryberry was also an avid performer in theater during her undergraduate career. The artist suggests, “The idea of multiple personalities/personae really engaged me, and I think that is still being played out in my paintings. I paint some of the same people over and over again, but in each piece the persona is slightly different according to lighting, composition, body language, and costuming.”

For nearly a decade, Derryberry’s work has increasingly explored alchemy, a Medieval philosophy based on the principle of rebis — “a belief that most aspects of human nature — and nature in general — are built on the idea of dialogue and contrast,” as Derryberry states. In fact, a number of artists influential to Derryberry, such as Michelangelo Caravaggio, have also found dichotomy and alchemical principles captivating.

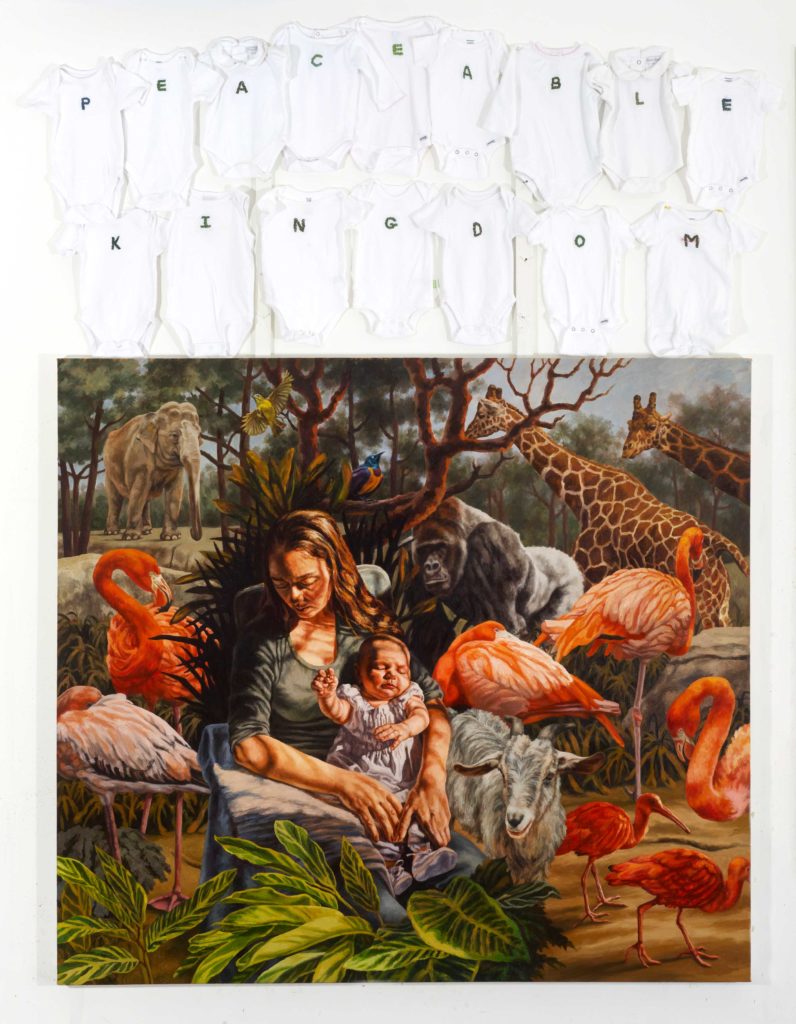

“Peaceable Kingdom” is an outstanding work that brings each of these concepts and influences to the fore. Derryberry explains how Da Vinci’s “Madonna of the Rocks,” Edward Hicks’ “The Peaceable Kingdom,” and other paintings led to the realization of this magnetic picture: “‘Peaceable Kingdom’ began as a portrait and figure narrative to honor my daughter, Elizabeth, and the birth of her daughter (my granddaughter), Virginia, in 2012. I decided to combine a Madonna and Child format (actually a reference to Da Vinci’s ‘Madonna of the Rocks,’ where Jesus is holding up his hand to John in blessing) with Edward Hicks’ version of ‘The Peaceable Kingdom.’ I’ve always loved the naïve quality of Hicks’ paintings and especially his reference to the idea of the ‘lion laying down with the lamb.’ What struck me about the imagery in this painting is how much the wider environment is included and how it suggests a return to the Garden of Eden. Combining three mythic stories in one — the Garden of Eden, an otherworldly mother and child story, and the possibility of wild animals at peace with one another and humanity — excited and challenged me. My other intent was to go past the Biblical story and to suggest the here and now in terms of the complex struggle that we, as humans, have with finding a peaceful relationship with our environment.

“A contemporary aspect is my use of 16 ‘onesies’ (actually worn by Virginia over time) that I embroidered with the letters of the title. I think their inclusion suggests many things — a larger life and experience beyond one particular child, a ‘levity’ that plays against the gravity and physicality of life, and even the suggestion of cloud forms over the earth. Many of these, of course, reference alchemical imagery as well.”

Derryberry’s primary goal with works such as “Peaceable Kingdom” is twofold, involving both confusion and revelation. The play between the two offers a chance for viewers to ignite self-inquiry while participating in the discovery of the narratives. Derryberry writes, “I try to guide the viewer first to be puzzled about what they are seeing. For example, sometimes I deliberately use conflicting light sources or I put in an object or form that simply doesn’t belong. Secondly, I want the viewer to be lured into the painting due to the color and sensuality of the surface, caught, if you will, by the complex paint passages. Once they are in there for a while, hopefully they start to ask questions of the image and, ultimately, questions about themselves. That’s the main reason that I address multiple story lines in a painting — so that I am not deliberately illustrating a specific message but asking for a more metaphorical interpretation.”

As Derryberry’s teaching career in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of North Carolina at Asheville concludes, one might assume the artist is fading into the sunset. But the truth is quite the opposite. With teaching playing a decreasing role in Derryberry’s life, personal ventures in painting await through a number of solo exhibitions, and artist residency programs in France and Italy. “I have scheduled four upcoming solo exhibitions, titled ‘Private Domain,’” she says, “essentially a traveling exhibition to four separate venues over the next two years, which will give me the opportunity to explore how viewers — mostly college students — react to my work.”

To learn more, visit Virginia Derryberry.

This article was originally published by Andrew Webster in 2017.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter